The title will make sense next post.

I haven’t written here much lately due to an inability to choose among the rich possibilities of commenting on the mass stupidity of my fellow countrymen. Sorting through the morass of charges and justifications for the last four years, I’ve come to a conclusion (which I will hold until new evidence suggests I have it wrong) that nothing from the Fox News-driven fanatic fringe has anything to do with policy. From what I can glean from everything I’ve seen, a significant number of people either don’t care or wouldn’t understand policy issues. That’s why there appears to be no compromise.

I suppose one way to look at it is, the segment of the population I grew up hearing constant lectures from about morality and duty, patriotism and decency, have faltered over one of the social axioms they often threw at people of my generation, that we didn’t know the difference between love and lust. It would seem that they have marched on to the present having gotten that backward themselves.

Lust, in this case, is that mix of emotions wherein one wants to possess something and will do, believe, say, or try anything to have it. Whether it wants to be possessed or even if it can be. Nothing is acceptable that seeks to deny the possessing.

It is often mistaken for love because, on the surface, it seems such a positive thing. The object is not something to be harmed or destroyed, all the lustful wants is to enjoy it. And I would venture to suggest that, in very small doses, constrained by self-knowledge and a solid understanding that the aspects lust shares with love are not necessarily harmful—desire, admiration, even a modicum of appreciation. Lust can morph into other things, and within something like love it can fuel moments of ecstasy. But not if it stays locked in the possessive mode.

But lust alone is utterly destructive, for the simple reason it does not allow for choice or change. Which is what love not only allows but requires.

So let me get right to it:Â to love your country is allow for choice and to allow for change.

Sounds simple. In fact, to love another person is to allow for choice and change. Not only allow for it but embrace it. And by embrace I do not mean happily accepting every damn whimsical thing that might come along, but to support the idea, the right to choice and change and to be an active participant.

To insist it be one thing, the same thing, forever, and if it is not, to condemn it, strike it, to violate it…

One of the drawbacks of lust is that it almost entirely has to do with surfaces. Appearances. All the rest is part of an imagined substance, and imposed ideal. No thought is given to the interior of the object desired.

I’m using this as an example for what I perceive as a major aspect of the current mass of rightwing affectation. The people responsible for January 6th are abusers. They may well be sorry they hit the one they claim to love, but they did it, and unless the victim adheres to an impossible standard of corrupted fidelity, they will do it again. Which means, as far as I’m concerned, they do not love their country. They want it, they feel they have a right to control it, they cannot stand the thought that someone else might have a claim on it, and they certainly don’t accept that the evolution driven by democratic involvement is the way things are supposed to work. They want it chained to a form that allows them to dictate where it can go, what it can do, who it can be, and allows for no say from anyone else, not even fellow citizens who just might have a different idea of what the relationship is supposed to be.

Absurd? Maybe. But the events leading up January 6th and the sentiments expressed during and in the aftermath suggest to me a pathological ideation akin to an obsessive who feels a variety of proprietorship similar to a compulsive spousal abuser.

Which means we can discuss policy till the sun expires and it will make no difference. This isn’t about how the country should be managed, and reasonable discourse has no traction.

All of which ultimately funnels through a doctrinaire refusal to be told what to do, not so much in general, but by the abused partner in particular. In this way the disparate causes of tax rebels, segregationists, anti-vaxxers/anti-maskers, deregulation hawks, and social program opponents come together in a discernible commonality.

And January 6th? “Well, if I can’t have her, no one can!”

The problem, though, is that what they seek to dominate, to control, is not a person, but an idea with supporting institutions. You can’t slap anything and expect it to cower.

Of course I exaggerate, but to be fair, the situation is so broadly farcical and a product of exaggeration, that gaining traction, to try to rationally address it, may require a bit of out-of-the-usual-box conceptualizing. The ground shifts too quickly and erratically for a consistent assault confined to “issues.” This is, in my opinion, largely a pathology.

Some sane politicians are beginning to deal with this for what it is. Compromise being not only impossible but impossible even to define, they’re moving on and dealing with tractable issues. Which will drive the obsessives to greater outrage, because that’s the sign of a victim taking back control of their life.

It tracks all the way down the line, from the national to the personal. There’s an element of narcissism to it, certainly, but several other things as well. In the end, though, when someone is more terrified of a solution than of the problem they’re living in, to the point where they won’t even entertain the idea of changing something that may be slowly killing them, then we have left the area of meaningful discourse. If, then, clinging to that problem means forcing everyone around them to live with it as well, then we are dealing with intractable dysfunction.

Yes, I am aware that this argument can be turned around, inside out, and used to justify exactly what I’ve identified as the problem by making it seem those trying to make changes are the ones unable to deal with reality. That happens. All that one can do then is keep in mind that continuing as we are may be fatal for everyone.

*****

On that cheerful note, other matters. Some changes are coming down the pike, fairly significant ones, which I will elaborate on in the next post. It’s good, maybe even all good. Perhaps not as good as I’d like or in the way I’d like, but good.

We’ve been living in weird times. The pandemic has deformed our sense of normal in many ways. I would venture to say some people have thrived. Being stuck at home would not, for the most part, be a bad thing for me, but I certainly would not want it to be total and unending. We haven’t taken a long trip in some time. Of course, given the mood of the country, staying home sometimes seems like a smart choice.

But I’ve reached that point in life where it seems falling into habits is easier and easier, and some habits would be traps more than simple routines. Getting into a habit that deflects from going forward, engaging life, doing all the things…we’ll exercise reasonable caution, but sitting at home, watching movies all the time, turning into an Old Man, no.

We have never traveled outside the United States. I’d like to, but there’s still plenty to see here. (I’ve never seen the Grand Canyon and we’d like to visit Chicago again.) If we don’t make it to another country, I will not feel shortchanged. I have learned that the best part of travel is who you’re traveling with and I have the best companion I could have hoped for. (She did hint a couple of years ago about the possibility of going to England. Then COVID shut the world down.)

*****

Professionally, things are…strange. I’ve now sold four stories to ANALOG, which is a market I never expected to crack. But Trevor, the editor who replaced the venerable Stanley Schmidt, is apparently much more open to my kind of SF. What I’m really excited about is that I now have two novellas in the queue! I would not mind if ANALOG became my primary market going forward, but it is a curiosity to me.

But on almost every other front things have stagnated. I heard a new term recently that disheartened me a little: post novel. Apparently, this has happened to a number of writers who at one point in their careers published novels and now—can’t. The market, the readership, the publishing environment in which they could, all that changed, and they have become post novel.

I’m sanguine. Every generation has experienced something like this. Most bestselling authors from the 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s are largely forgotten today, in any genre. It happens. Tastes change. What is perhaps different now is the speed with which this happens. One can watch one’s career decay over the course of a decade.

To be clear, I do not blame the influx of new writers or the changing æsthetic they bring. I do not feel sidelined by the purported rise of considerations regarding so-called political correctness. Those new writers are saying things in ways and about things that speak to an audience that responds with their dollars. Good for them. This is as it should be. In 20 years they may be “post novel” for the same main reason—tastes change, markets morph, language mutates. It is worth bearing in mind that when we talk about past eras of remembered writers and great books, we’re talking about the tiny handful of works that survived out of myriad forgotten titles and writers.

I’ve been lucky to write stories people found worth publishing. I got to play the game. Would I still like to do it? You bet, but I am mindful that I’ve gotten to do something so few ever get to do. It would be churlish of me (and really immature) to demand that time stop and the landscape remain as it was back then just so I could continue to be relevant (if I ever was). Freezing the world in place to gratify my desires would be criminal.

Hmm. That sounds familiar.

But I am still writing and I have my occasional sales. I may yet find a way to publish the novels I have ready to go, but I won’t insist on blocking anyone else just so I can.

I have been grinding away on a short story now for the past month which feels almost ready. And when I say grinding, I mean I’ve had this one “finished” several times. But it’s never been quite right. And right now it has me, it won’t let me step away to work on something else until it’s done. If I can pull it off I may well be about to accomplish something I’ve always wanted to do but never managed—do a series of shorter works with the same characters. If this one comes together and I manage to place it, it will be the third story about this particular cast.

I’m actually excited about the prospect.

*****

I’ve had my photography galleries up for quite some time. The work therein is for sale. I have in place the things I need to start doing more, and possibly some exhibition work. What I always failed to follow up on in my photography was putting it in front of people. For several reasons, I never engaged with that aspect. Every time I walked into a gallery to check it out, within ten minutes I felt put off. Partly this is dismay at some of the requirements, but there is also a deep fear of rejection.

Yeah, you’d think I’d have learned how to deal with that by now, after 30 years of publishing fiction, but it’s always there.

But if I want to put my art into the world, I have to get over that. So that’s on the agenda of upcoming reinventions of self.

So with that, I end this post. As I said, the title will make sense with the next post, which may be a a ways off. I’m busy, so I won’t be here for a bit. Never fear, I’m okay.

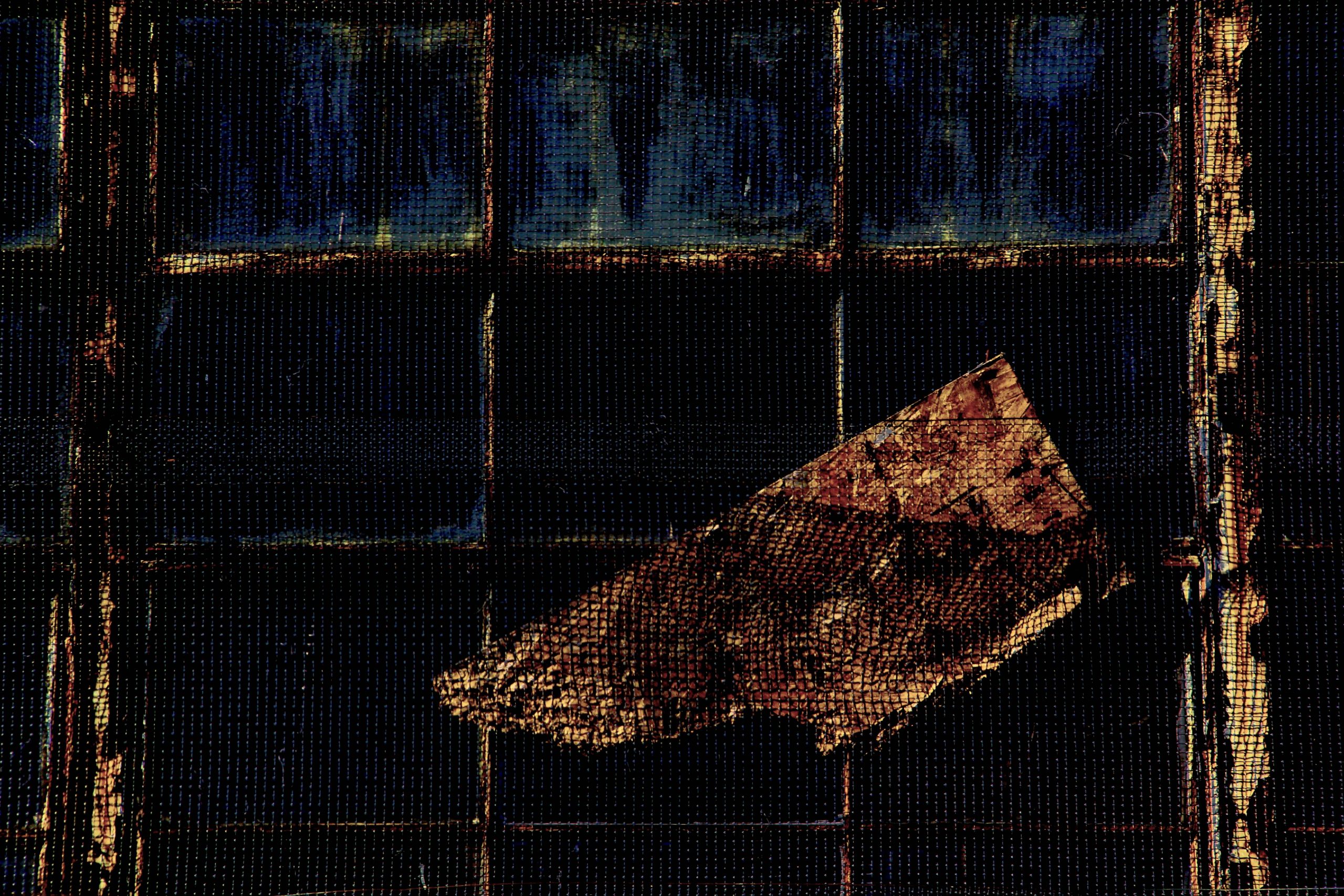

What follows is an assortment of images, some of which you may find in the galleries, and purchasable. (There, a shameless plug!) I leave them here for you to enjoy until we gather again for another update.

Be well.

*****