Category: blog

Memories

- Posted on

- – 2 Comments on Memories

Yes, it is my birthday. I’m 69. In another era I would be an Old Man…or dead. Instead, I seem to be fortunate in what vitality I have. I work at it, of course, but that’s not always a guarantee. I intend fighting decrepitude for as long as I can.

This year, my father died. He was 92. My mother is 88. I come from long-lived stock, so to speak.

But I thought today, for this, I’d depart a bit from the standard birthday celebration kind of reminiscence. Not sure if this will tie in, but what are anniversaries like this for if not for indulging memory?

I remember two homes growing up. There was a house, which we lived in till I was in 3rd grade, when we moved to a two-family owned by my grandparents. That led to some mixed feelings on all sides, but for the most part I was oblivious to all that. Around the age of 15 I took up photography. It went quickly from hobby to passion to potential career. I early on became enamored of the old masters—Adams and Weston and Bullock and Cunningham and all that later became lumped, accurately or not, in the f64 Group. The clarity of those images still holds me. Instead of the more current photographers of my youth, I worked to imitate those older artists, with their grandeur and depth, lugging around those enormous view cameras.

I was not successful at it for several years, but occasionally I got lucky. The light was just right, the scene presented itself as if begging to be photographed. So here is one with specific place memories if nothing else.

The backyard of my grandparents’ house was nothing much, but on one side there were paving stones instead of poured walkway. My grandfather was a fortunate and dedicated gardener and there were always flowers. One morning I stumbled out there with one of my enormous cameras—a 2 1/4 press camera, a Mamiya, designed for weddings and so forth, but which I often used as if it were a 35mm, an instrument for photojournalists—and found this image:

My method back then was to blaze away and sort through the negatives later. I suspect most photographers do something like that, whether they admit it nor not. I found that with time I got luckier and luckier. (Quite often I would snap a picture, not knowing why, and even wondering for some time after why I’d taken that shot, only to one day, fiddling in the darkroom, discover the gem in the confusion around it.) This one, though, I kind of knew when I framed it that it was a decent image. I did not pose it, despite the apparent intentional composition of the elements. It was just there.

I suppose you could say I’ve been lucky in my seeing. I’ve noticed things. Not always, and I’ll never know how much I did not see, but of the memories and material I have there are some fine things. And many of them I have concrete touch-points, a photograph or the thing itself, to remind me.

I’ve had a print of this one lying around for decades. I thought it time to share a small slice of time. It is my birthday, after all, and the past if what led to the present. This was something I thought beautiful found along the way.

If I Could Change One Thing

This is a wholly personal, largely confessional post. I’m telling on myself, though most people who know me will not be surprised.

From time to time you see these things online, which stem from old conversational gambits and party games. If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be and would you? There’s utility in these kinds of challenges. You don’t necessarily have to respond openly, but it might prompt you to do a little introspection, and that seems ever in short supply. Do an inventory, if you will. What loose ends are dangling that you might want to tend to.

After decades of playing that game, I’ve come to the conclusion that for the most part, I wouldn’t change much. I’m too aware of how all the things that comprise Me are so intertwined that deleting or changing one might cascade through the rest and I’d come out so different I wouldn’t know myself anymore. That’s a bit dramatic, perhaps, but not as ridiculous as it may sound at first blush. So one has to ask what would you change that would be worth that risk.

I hate to clean.

My entire life I have had this annoying aversion to cleaning things. A very childish attitude, but one that still attends my daily choices. It’s as if some part of me is saying “I cleaned that once, it should stay clean.” For the most part, I manage to clean things anyway, but once in a while I look around and say “Yeesh, what a mess” and I know I have to clean. Usually, “cleaning” to me is a surface thing. As long as you can’t see the mess, it’s fine. But we all know that surface mess usually rests upon a deep foundation of underlying mess that requires attention, and I hate it.

I envy people who can take pleasure in the process, or at least manage not to mind it. I can trick myself into it, but I can never find joy in the doing.

Which results in explosions of major cleaning at long intervals. I get so tired of the mess that I do a top to bottom, major overhaul, scrubbed from stem to stern, which I tackle as a kind of penance, loathing it even as I’m feeling a touch of redemptive self-righteousness while engaging the chaos. I hear the voices of past adults telling me “well, if you just kept up with it, it wouldn’t get this bad.” I am brilliant at finding myriad excuses not to “keep up with it.”

As a child, I recall my parents and my grandmother trying to school me in Being Neat. From time to time they would organize my toys. They would finish and point it out to me that if I put a toy back when I was done playing with it, then it would stay neat. And I would agree. And by the next day, the toys were all over the place, all order destroyed. After all, being “in their place” was never what toys were for. But that didn’t matter. I just found it impossible to maintain the presence of mind to follow through.

They say that disorder and chaos are signs of high intelligence and creativity. Maybe. But honestly, if there were ever one characteristic of mine that I would love to change, it is that aversion to cleaning. I wouldn’t even need to love it, just find it a congenial thing to do regularly, and not have this deep, generally unacknowledged dislike of the actual doing. I do enjoy cleanliness, neatness, orderliness. I do. I just hate the required work.

That one I think would be worth the risk that other aspects of myself might be altered if corrected.

There’s reason for this contemplation, which I will tell you all about later.

Thank you for your attention.

Feeling A Bit Horizontal

The novel is proceeding apace. Having come to a pivotal moment, I tend to step back, appreciate what is there (or not) before continuing on. While pausing, I do other things, like music or photography. So…

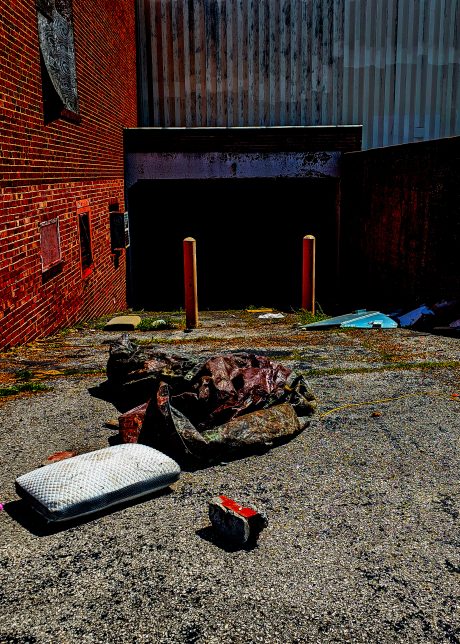

Down There

Things are happening. Slowly. At this point, the plan is to see the cool parts and ignore the annoying parts. I have an urge to cuss, richly and with feeling. But.

Making something cool out of the uncool is an impulse I get to indulge in weird ways. Â With all that vagueness, something emblematic.

Simpler Complexities

There are times I wonder why I do what I do. I mean, the thought occurs that there are simpler things in life. How did I ever convince myself that I could be a writer?

I cannot retrace the steps, not at this point. Somewhere back in the restructured haze of youth I had this idea that it would be cool to tell stories and get paid for it. I can do that, I can make things up, I do it all the time, all I have to do is write it down and send it in.

Well, I will not retrace the learning that showed me how wrong I was about my abilities. Death by a thousand rejection slips.

I’ll admit, I was baffled. I don’t know about others, but for a time I honestly could not see a difference between what I read in the magazines and what I was putting down on paper. You just tell what happens next. What does logic have to do with it? Life doesn’t follow rules like that, why should fiction? And this is science fiction, so rules should apply even less. I mean, what does it mean, it doesn’t make sense?

Because I did not know any of the rules, not even the rules of submission, I received no feedback in those early attempts, and drifted away into something else. Something I thought would be simpler. As much as I appreciate complexity as such, I was not good at creating it or dealing with it. How I managed to reach adulthood with any capabilities at all is one of those mysteries never to be fully—or even partially—answered. It was never that I thought the rules didn’t apply to me, it was that I never recognized the rules.

And still I managed.

It’s remarkable that I’m even alive.

But there were guardrails. My parents, other adults in my life, the rough outlines of general rules, a certain unexamined caution in my approach to daily life. And limited opportunities to get in over my head. In many ways, I had a sheltered upbringing.

That and I read. (One of my favorite films is Three Days of the Condor and one of my favorite scenes is the one where all these CIA operatives are discussing Robert Redford and how dangerous can he be. He has no field experience, why are we worried. “He reads,” Cliff Robertson tells them. Clearly most of them don’t get it. I loved that. He reads.

I read. A lot.

Not as much as I once did, but I retain more now, so it balances out. While I can’t point to a specific example (other than in a debate or argument) where having read something made a difference in a given situation, the cumulative effect has been like a form of experience.

I grew up at a time in a place soaked in the kind of received nonsense that requires outgrowing. At one time or another I have believed a great many false narratives, especially about the relative value of different people, different kinds of people, and like most of the people around I would let proof of my beliefs dribble from my mouth from time to time. Some of my contemporaries, no doubt, never grew out of that. For whatever reason, I was fortunate in a disposition that made it impossible for me to categorize anyone I personally knew according to prevailing stereotypes, and by extension whatever group they supposedly represented. Little by little, over time, I left a great many prejudices behind. Can I take any kind of credit for that? I’m not sure. The simplistic veneer of easy discrimination always gives way to the complexness underneath, and I have always preferred to embrace the complex—even when I didn’t understand it. And what I eventually understood is that prejudices, especially towards people, are products of simplistic thinking. The defense of such thinking, when pursued far enough, results in complicated structures that ultimately will not even support themselves. That genuine understanding results in simpler structures that allow us to see clearly.

Because I have learned (eventually) that complex is not the same thing as complicated and that often, perhaps usually, complexity manifests in simple forms. When we examine the properties of a nautilus shell, we see something quite simple in presentation. We can take it in at a glance and appreciate what it is fairly easily. It is a simple thing. But the layers of complexity is contains and offers up with investigation amaze us and lead to a trove of questions which, pursued diligently, offer up a glimpse into the underpinnings of the universe. A simple tune, easy on the ears and elegantly comprehensible in its performance, yields up myriad mathematical, harmonic, and even cultural aspects, an onion in its layers, beautiful complexity that manifests in simple melody and harmony. As noted by Samuel R. Delany, a simple declarative sentence—The door dilated—unpacks in ways that suggest an entire civilization beyond the threshold, all the assumptions necessary to result in the logic of that sentence and what it tells us.

Learning to see the two in collaboration can give us a more satisfying experience of life itself.

As a youth, I was dazzled and delighted by the complexities. Sometimes I mistook complications for complexities. Detail can fascinate, even when it might not add up to anything coherent. A consequence of age and continual observation is that I learned to see the whole where before I might only have seen the components. The art of recognizing and assembling complex ideas and details to create a comprehensible something is the art of recognizing that elegance, truth, and understanding should not confuse. We strive for clarity, which usually presents as simplicity.

But like the misidentification of complexity with complication, we have to learn to tell the difference between simplicity and the simplistic.

Thank you for your attention while I did some sorting.

On The Road, Off The Road, In Between

We attended an out-of-town convention last week, the first we have done together in many years, the first I’ve done since 2015. I made a policy not to go on the road when I have nothing to promote. The exception to that is the chance to see friends who will be at a con or who live nearby and the dates just happen to coincide. In this case, two of our favorite people live in Pittsburgh and seeing them was the deciding factor in choosing to attend Confluence.

Confluence is a small local convention that has in the past been surprising in what it offered, namely the chance to sit down with writers I respect and admire. I’ve had breakfast with Gene Wolfe, longish conversations with Michael Swanwick, met William Tenn (Phil Klass). The panels are of interest and usually the interaction with fans has been on a high level. I like the people who run it. They do a good job.

But it’s quite a drive from St. Louis to Pittsburgh, and while it has become a familiar one, we are older and more susceptible to road-burn. The weather was pleasant enough going up and it remained moderate while we were there, but it was hot coming back and we return to a scorching week. It’s Friday and I’m still recovering.

One off-site event was fascinating. Friday morning, before the con got started, a small group of us drove into the city to tour a church with some amazing murals. St. Nicholas in Millvale. Go to site, take a look. A Serbian artist named Max Vanka painted murals over most of the interior and they are amazing. Done in stages, from World War I on, they are more than just religious paintings, and they are radiant. There is an organization trying to save them (watercolor over bare wall, the leaching is bad) and I commend you as an art lover to help if you are so moved.

You might wonder, knowing me, why I would marvel and support something like this. Religion aside, which I could not care less for, these are works of art. This is the product of people of skill and imagination. The passion is evident.

After that, we returned to the hotel (out by the airport) and spent a few days being fans. I reconnected with some folks I haven’t seen in some time. And we spent time with our friends, Tim and Bernadette, who are amazing. We needed a longer stay, but alas.

Confluence, as I mentioned, is good convention. They take science fiction seriously and are good to their guests. But I will tell you that I’m now of a disposition that I’m less inclined to just pop into a town, especially that far away, for just the con. Next time we will take more time, do other things, relax. The in-between time from the road is the vital part, even though we generally like traveling. I want to take things more leisurely in future.

Next up, SF-wise, is Archon. Perhaps I’ll see you there.

Meantime, it’s good to be home….and not moving.

Courtroom Chaos

I answered my civic summons to jury duty this week. One day, Monday. I confess to being annoyed by this as I have Things To Do this week and would have preferred another week. I do not object to being called to jury duty. I think it’s important. The last time, I was selected but never got the chance to serve because the judge had had a ruling overturned and they had to start all over. I was disappointed in that one, it would have been fascinating as both lawyers appeared to be at the top of their game and it was a murder trial with some interesting features. Ah, well.

This time, though it was a civil case.

I reported to the court building on time, got my number, and settled down to read a book until called. As it turned out, I only got 20 pages read before that, and I was the third number called.

It became clear fairly quickly that this was not something that would be especially interesting (in fact, about 30 minutes into voir dire I more or less deduced the issue). An insurance suit, the twist being that the plaintiff was suing his own insurance company. There was man at the defendant’s table wearing a rather ordinary polo and a drawn, permanently discommoded expression who was the representative of the insurer. The plaintiff was a rather well-dressed man who did, after watching him for a time, seem to be limited in his movements. The lawyers seemed competent if underwhelming. This was a bookkeeping matter that had gotten contentious and if my assumption was correct, my sympathies already lay with the plaintiff.

The complication—and the reason for the suit—was that the driver who had caused the accident at the heart of all this had fled and no one knew who he was, so he/she and their insurer could not be sued. (My assumption therefore is that the plaintiff filed an injury claim with his own company and was denied.)

We all had little white paddles with our seat number and when answering questions or asking them we were to hold them up so the court recorder could efficiently identify us. The plaintiff’s attorney finished up by lunch, we broke for food, and returned for the defendant’s attorney.

That’s when things got interesting.

He wanted to establish that we could all fairly judge the facts of the case (fair enough) and treat the insurance company like any other person. He then pointedly asked if we could accept the company as a person.

I felt a tingle over my scalp.

Several paddles went up to admit that, no, we could not. He then said, “Corporations, according to the law, are people. Do you disagree with this?”

Someone said, “No, I can’t. Corporations are not people.”

“Anyone else feel this way?” the lawyer asked.

And a flurry of discussion erupted around the jury pool about that. When it wound down, he pushed “Even though it’s the law?”

That’s when I opened my mouth. “It is the law, but we all know it’s a legal fiction. It’s used as a convenience to circumvent certain procedural difficulties for the purpose of an expedited trial. Of course a corporation is not a person. An individual generally doesn’t have a machine behind them.”

He blinked at me. “What does that matter?”

“Well,” I said, “you can’t actually put a corporation on the witness stand. At best, you get a representative. He’s limited in what he can say by prior instructions. The entity giving the instructions is not actually present. Responsibility becomes a moving target.”

Everyone—all the lawyers, the court clerk, the judge, many of the potential jurors—was staring at me. The defendant’s attorney’s mouth opened, then closed.

And then several people pointed at me and said “I agree with what he said.”

The questions wrapped up quickly then and we were sent out of the courtroom while the selections were made. In the hall, a woman came up to me.

“Are you a lawyer?”

“No, I’m a writer.”

“Oh. What do you write?”

“Science fiction.”

“Oh, well that figures,” she said and walked away. I wanted to ask what she meant, but I never got the chance.

When the selections were made, not one of the people who had voiced doubts about corporate personhood was chosen. Predictable if a bit disappointing. As we were all receiving our slips of paper confirming our service, several people smiled at me. I assume they all had pressing matters to attend that jury duty would have made more difficult.

Thus endeth my current civic duty. I do have to wonder what they would have done had everyone in that pool voiced the same skepticism. Well, draw another pool, yes. But then…

A Mechanics Of Grief

We have an emotional field, generated by what goes on inside. Much like a gravity field, the space-time field, it distorts in the presence of other bodies. The degree of distortion is relative to the size of their presence in your life, which can explain why someone we never met can be the cause of genuine grief when they’re gone. That well created in the field you project is a result of how much value you put on their place in your life.

The orbits thus created shift and jostle for equilibrium. When one disappears…

Back in the Age of Burgeoning Awareness (the Sixties through the Nineties) many introspection disciplines advised us to leave nothing unsaid. Finish your business, lest the chance vanish in a puff of mortality. Having undergone a degree of this in an attempt to find handles on various dilemmas, I took this one to heart. The first time its utility was tested, I fell apart at the seams. I did not feel okay, even while being relieved that the suffering of my departed friend was over. It’s not so much that the advice was wrong, but they say nothing very useful about what comes of it. Judging the success of something by an absence is frankly impossible.

People die. They leave a space in our lives they once occupied and that emptied space must be dealt with, because it exerts a pull on us and now that mass is gone. Adjustments must be made. The reassessments of going on with a new relation to our living ecology is required and you simply cannot do that in advance. Those spaces they occupied in your life supplied stabilizing effects. We relied on them to be there for navigation. Remove one and we have to find a new stability.

That is even before the emotions unleashed by loss come to the fore.

Not every loss that causes grief is a necessarily close or even active relationship. The weight of their importance in your life is not always of their doing.

But when it is, when it is mutual, when it goes both ways, that sudden absence can be seismic.

We are taught to assign reasons to things, especially important things. Why this, why that. We reduce to detail, catalogue, justify. We want to seem reasonable and, often, unfazed, especially by things which by their nature unhinge us. We want to understand, of course, but also we want to appear to understand, for, among other reasons, those around us who need us to understand so they might anticipate understanding themselves. We start negotiating with the universe to somehow let us be all right with what was never in our power to do anything about.

Someone dies. Their position in our ecology is suddenly empty. Memory remains, of course, and those around who who also had them in their fields remind us, but there is now a hole where once a person was, someone who affected us, influenced us, drew us along pathways in a complex web of tangled suasion along with others, who they also drew along, and by so doing added to the total set of forces molding our journey through life. Gone, that complexity must readjust, find new equilibrium. That unbalancing creates a sense of powerlessness. It hurts. Just by its absence.

Things will come back into equilibrium. Not the same kind and the difference may linger to haunt us with a sense of not quite right. And it will happen again. And again.

Trying to pretend nothing is changed or that you were all right with the loss or any of a dozen other sophistries to avoid the ache…it only hurts in a different way, but it doesn’t ever not hurt.

My father died on May 19th. These are some thoughts I had in the aftermath. He isn’t there anymore. It feels off. I miss him.

That Kind Of A Week

Because I really don’t want to write anything heavy or long, accept a couple of new photographs. I’m fine, I just need to recoup.

Thank you.