I watched the Bill Moyers interview of social psychologist Jonathan Haidt with great interest. Haidt tried to describe what has essentially become what might be called the Two Nations Problem—that is, that America, the United States, has become in many ways two very distinct countries.

At its simplest, what this means to me is that people, using the same documents, the same laws, and the same presumptions of national character, have created two very different narratives about what it means to be an American. Quite often these beliefs overlap, but at the extremes such instances are ignored or treated as anomalies or expressions of hypocrisy.

It might be reassuring to keep in mind that it is at the rhetorical and ideological extremes where this happens, that the larger portion of the population is between the extremes, and by inference less rigid in their misapprehensions of both sides, but in reality this may not matter since it is those who establish the most coherent narratives who dictate the battle lines. And we have come to a point where a willingness to hear the opposite viewpoint gets characterized as a kind of treason.

As an example, try this: for the Left, any suggestion that corporations are important, vital, and often do beneficial things for society is relegated at best to a “So what?” category, at worse as an attempt to excuse a variety of evils committed in the name of profit. For the Right, any criticism of the shortcomings of corporations and attempts to regulate activities which can be demonstrated as undesirable is seen as a direct attack on fundamental American freedoms.

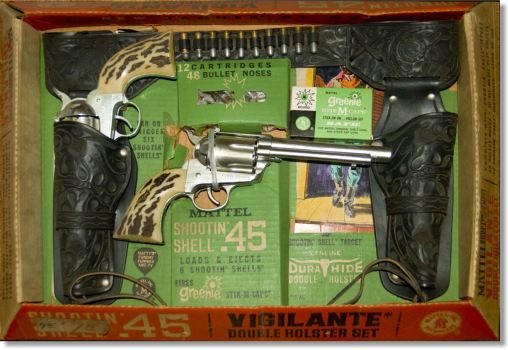

We can go down the list. Attempts to regulate the distribution and availability of firearms is seen by the Right as a threat to basic liberties while for the Left the defense of an absolutist Second Amendment posture is seen as irresponsible at best, the promotion and propagation of a culture of violence at worst. Environmental issues divide along similar lines—for the Left, this is, using Jonathan Haidt’s term, sacred, but for the Right is again an assault on the freedoms of Americans to use their property as they see fit. And taxes? For the Right, taxes have become a penalty, for the Left a kind of grail for equitable redistribution of wealth.

Tragically, none of these hardened positions—none—addresses the reality of most Americans’ lives.

Oh, there’s some truth in all the positions, otherwise it would be simpler to dismiss them. But the hardest truth to get at is the one being used to advance a false position.

What Haidt suggests—and I’ve heard political strategists talk about this—is that the difficulty lies in the particular narrative embraced. The story we use to describe who we are. In the past, that story has been less rigid, porous in some ways, and flexible enough to include a variety of viewpoints from both Left and Right, but in recent years both narratives have taken on the stolidity of religion.

But the related problem is that really there’s only one narrative, at least one that’s cogent and accessible, and that happens to be the one best described as conservative.

Recently, I’ve been giving thought to this dichotomy of Left-Right, Liberal-Conservative. I’ve been uncomfortable with it for a long time, but have found myself shoved into the Left-Liberal camp as a reaction to policy proposals I find unacceptable which always seem to come from the Right-Conservative side. In the hurly-burly of political competition, sometimes there isn’t room for the kind of nuance which, say, historians can indulge. You find yourself defending or attacking in an attempt to preserve or change and the finer points of all positions are reduced to sound-bites and slogans. I’ve never been particularly pleased with the welfare system, but faced with conservative assaults that seem determined to simply tear it down and leave a great many people without recourse has found me defending it against any criticism that seems aimed at finding a reason to end it. It has always seemed to me that people opposed to it are not interested in offering a viable alternative (“They should all get a job!”) and dismantling welfare would do nothing but leave many millions of people with nothing.

But nuance, as I say, gets lost. I don’t care for the way in which welfare is administered, but that’s not the same as saying we should not have a system for those who simply cannot gain employment. And in the economic environments of the last forty years, it is simply facile posturing to suggest there are plenty of jobs. If you want to see a real-life consequence of the kind of budget cutting being discussed, look at the upsurge of homelessness after Reagan gutted the HHS budgets and people who had been in mental hospitals were suddenly on the streets.

But I don’t want to continue the excuse making. The problems Haidt elucidates have to do with an avoidance of reality on both sides and a subsequent process of demonizing each other.

And with a political mischaracterization that has resulted in the alienation of a great many people from both camps. Often such people are given the broad and thoroughly undescriptive label Independent. I consider myself that, though I have voted consistently Liberal-Democrat since 1984. (Admission time. I voted for Nixon in 1972 and I voted for Reagan in 1980. In hindsight, it would seem I had always been looking for the Other Designation—Progressive—for which to cast my ballot, but that’s a very slippery term. Reagan was the last Republican I voted for in a national election. I have felt consistently alienated by GOP strategies and policies, but the reality has been that my votes for Democrats have usually been “lesser-of-two-evils” votes, not wholehearted endorsements. Until Obama. He was the first presidential candidate since John Anderson in 1984 who I felt actually had something worthwhile to offer rather than merely a less odious choice to the Republican.)

Once upon a time there were Liberal Republicans. There are still Conservative Democrats. But I think in general we no longer know what these terms mean. The narrative that has been driving our politics since Reagan has buried them under an avalanche of postured rhetoric designed to define an American in a particular way that no doubt was intended to transcend party politics but has instead cast us all in a bad Hollywood movie with Good Guys and Bad Guys in which a final shoot-out or fist-fight determines the outcome.

I think it is fair to say that this America is ahistorical. On the Left, it is a country demanding atonement, built on the backs of the abused and misused, hypocritical, concerned only with power and wealth. On the Right is the only country ever that has offered genuine freedom for its citizens and has stood on the principles of fairness and justice (which are not always the same thing) and because it has done more good than not its sins should be absolved if not ignored.

Neither portrait is true, although many true details inform both.

What perhaps needs to happen is for new storytellers to come to the fore. I’m not sure how they’re going to be heard through the constant din of invective-laden blaming, but I think Obama took a stab at it. He got drowned out more often than not and didn’t finish constructing the narrative, but he seems to have a grasp of how important the story is.

Because here, almost more than anywhere else, the Story is vital. When we broke free from England, our story up till then had been England’s story, and it was long, deep into the past. When we stepped away from that it was into political and social terra incognito, and if there was going to be a story for us it would have to be one that looked into the future. We had no past at that point, not one we could claim as our own. We have been constructing that narrative ever since.

Here’s where the crux of the problem now lies, I think. For one side, there is the sense that we finished the story quite some time ago and that it is fine as it was and should go on unmodified. For the other side, that narrative is too filled with burdens of a past it seems no longer applies. This ex stasis has left us in a kind of limbo. Neither side seems willing to admit that the other might have something of value to add to the narrative and that maybe some of the narrative went off the rails here and there. Neither side wants to admit that their version of who we are really needs the other as well. Until that occurs, those caught in the crossfire find themselves having to pick and choose the parts of both narratives that work for them and then figure out which way to go with the hodge-podge so assembled. By these means we lurch on into an uncertain future.

I’m likely going to revisit this from time to time. For now I think I want to do without labels. But I’ll leave off for now with this: My Way Or The Highway is absolutely idiotic when we’re all still building the road.