and

Forgive the “ads” but there’s not much I can do about them. Please…enjoy.

and

Forgive the “ads” but there’s not much I can do about them. Please…enjoy.

I cannot adequately tell you how I feel right now. My insides are being roiled by a gigantic spoon.

Chris Squire, bass player, co-founder of in my estimate one of the greatest musical groups to ever grace a stage, has died.

A brief report of the particulars can be read here.

I have been listening to, following, collecting, and appreciating YES since I first heard them late one night on my first stereo, a track being played as representative of an “underappreciated” band. That status did not last long. A year or two later, they were a major force in what has been called Progressive Rock, a label with some degree of oxymoronicalness in that, not a decade before their advent, all rock was progressive.

Rather it was transgressive and altered the landscape of popular music. By the time YES came along, divisions, subdivisions, turf wars of various arcane dimensions had become part and parcel of the scene, and there were those who found YES and others like them a transgression to some presumed “purity” of rock music that seemed to require simplistic chord progressions, banal lyrics, and sub par instrumental prowess. As Tom Petty once said, “Well, it was never supposed to be good.”

Well, I and many of my friends and millions of others, across generations, thought that was bullshit, and embraced their deep musicality, classical influences, and superb craftsmanship. They were a revelation of what could be done with four instruments and a superior compositional approach and as far as I’m concerned, Punk, which began as an intentional repudiation of actual musical ability, was a desecration of the possibilities in the form.

Chris Squire and Jon Anderson met and created a group that has since become an institution, with many alumni, that challenged the tendency of rock to feed a lowest-common-denominator machine. Nothing they did was common, expected, or dull. Some of it failed, most of it elevated the form, and all of it filled my life with magic.

The ache felt by many at the loss of George Harrison is the ache I now feel at the loss of Chris Squire. He was brilliant.

There may be more later, but for now, here is an old piece I wrote about YES.

First off, I would like to say that I work with some amazing people. I will address just how amazing they are in a different post. The reason I mention it here is that this morning I attended a meeting wherein we all discussed an extremely delicate, profoundly important issue in order to establish a protocol for a specific event and it was one of the most trenchant and moving experiences in which I’ve been involved.

In mid-July, Harper Lee’s novel, Go Set A Watchman, will be released. That I am working at a bookstore when this is happening is incredible. That I am working at a bookstore with the commitment to social justice and awareness that Left Bank Books brings to the table is doubly so, and one of the reasons I feel privileged is the discussion we engaged this morning.

It concerned a particular word and its use, both in Harper Lee’s novel To Kill A Mockingbird and in the larger community of which we are all a part. Necessarily, it was about racism.

I’ve written about my experiences with racism previously. One of the startling and dismaying aspects of the present is the resurgence of arguments which some may believe were engaged decades ago and settled but which we can now see have simply gone subterranean. At least for many people. For others, obviously nothing has gone underground, their daily lives are exercises in rehashing the same old debates over and over again. Lately it has been all over the news and it feels like Freedom Summer all over again when for a large part of the country the images of what actually went on in so many communities, events that had gone on out of sight until television news crews went to Alabama and Mississippi and Georgia and the images ended up in everyone’s living rooms often enough to prick the conscience of the majority culture and cause Something To Be Done.

What was done was tremendous. That an old Southerner like Lyndon Johnson would be the one to sign the 1964 Civil Rights Act into law is one of the mind-bending facts of our history that denies any attempt to reduce that history to simple, sound-bite-size capsules and forces reconsideration, assessment, and studied understanding that reality is never homogeneous, simplistic, or, more importantly, finished.

It became unacceptable for the culture to overtly treat minorities as inferior and allocate special conditions for their continued existence among us.

Those who objected to reform almost immediately began a counternarrative that the legal and social reforms were themselves the “special conditions” which were supposed to be done away with, conveniently forgetting that the level playing field such objections implied had never existed and that the “special conditions” that should have been done away with were the apartheid style separations and isolations these new laws were intended to end and redress. Pretending that you have not stepped on someone for so long that they no longer know how to walk and then claiming that they are getting unwarranted special treatment when you provide a wheelchair is about as disingenuous and self-serving as one can get, even before the active attempt to deny access to the very things that will allow that person to walk again.

Some of this was ignorance. Documentary films of southern high school students angry that blacks would be coming into their schools when they had schools “just as good as ours” can only be seen as ignorance. Spoon fed and willingly swallowed, certainly, but the cultural reinforcements were powerful. The idea that a white teenager and his or her friends might have gone to black neighborhoods to see for themselves whether or not things were “just as good” would have been virtually unthinkable back then. Not just peer pressure and adult censure would have come in play but the civic machinery might, had their intentions been discovered, have actively prevented the expedition.

But it is ignorance that is required to reinforce stereotypes and assert privilege where it ought not exist.

Bringing us to the present day, where one may quite honestly say that things have improved. That African-Americans are better off than they could have been in 1964. That for many so much has changed in two generations that it is possible for both sides to look at certain things and say, “hey, this is way better!”

Which prompts some to say—and believe—that the fight is over.

And the fact that it is not and that the arguments continue prompts some to believe it is a war and that the purpose of at least one side is hegemony over the other.

Which leads to events like that in Charleston and Dylann Roof’s savage attack. He’s fighting a war.

The fact that so many people have leapt to excuse his behavior demonstrates that the struggle is ongoing. I say excuse rather than defend, because with a few fringe exceptions I don’t see anybody hastening to defend his actions. What I see, though, are people taking pains to explain his actions in contexts that mitigate the simple hatred in evidence. For once, though, that has proven impossible because of Roof’s own words. He was very clear as to why he was doing what he did.

He is terrified of black people.

Irrational? Certainly. Does that mean he is mentally ill? Not in any legal sense. He has strong beliefs. Unless we’re willing to say strong beliefs per se are indicative of mental illness, that’s insufficient. That he is operating out of a model of reality not supported by the larger reality…?

Now we get into dicey areas. Because now we’re talking about what is or is not intrinsic to our culture.

Without re-examining a host of examples and arguments that go to one side or the other of this proposition, let me just bring up one aspect of this that came out of our morning staff meeting and the discussions around a particular word.

After the Sixties, it became unacceptable in the majority culture to use racial epithets, especially what we now refer to as The N Word. We’ve enforced social restrictions sufficient to make most of us uncomfortable in its use. In what one might term Polite Society it is not heard and we take steps to avoid it and render it unspoken most of the time.

To what extent, however, have we failed to point out that this does not mean you or I are not racists. Just because we never and would never use that word, does that mean we’ve conquered that beast in ourselves or in our culture?

Because we can point to everything from incarceration rates all the way up to how President Obama is treated to show the opposite. But because “race” is never the main cause, we claim these things have nothing to do with it. We have arranged things, or allowed them to be so arranged, that we can conduct discriminatory behavior on several other bases without ever conceding to racism, and yet have much the same effect.

Because in populist media we have focused so heavily on That Word and its immediate social improprieties, we have allowed many people to assume, perhaps, because they’ve signed on to that program that they have matriculated out of their own racism and by extension have created a non-racist community.

That’s one problem, the blindness of a convenient excuse. Put a label on something then agree that label represents everything bad about the subject, then agree to stop using the label, and presto change-o, the problem is gone. Like sympathetic magic. Except, deep down, we know it’s not so.

The deeper problem, I think, comes out of the commitment, made decades ago, to try to achieve a so-called “colorblind society.” I know what was meant, it was the desire to exclude race as a factor in what ought to be merit-based judgments. No such consideration should be present in education, jobs, where to live, where to shop. We are all Americans and essentially the same amalgamated shade of red, white, and blue. (Or, a bit crasser, what Jesse Jackson once said, that no one in America is black or white, we’re all Green, i.e. all classifications are based on money. He was wrong.)

While there is a certain naïve appeal to the idea, it was a wrongheaded approach for a number of reasons, chief of which it tended to negate lived experience. Because on the street, in homes, people live their heritage, their family, their history, and if those things are based, positively or negatively, on color, then to say that as a society we should pretend color does not exist is to erase a substantial part of identity.

But worse than that, it offers another dodge, a way for people who have no intention (or ability) of getting over their bigotry to construct matters in such a way that all the barriers can still be put in place but based on factors which avoid race and hence appear “neutral.”

Demographics, income level, residence, occupation, education…all these can be used to excuse discriminatory behaviors as judgments based on presumably objective standards.

This has allowed for the problem to remain, for many people, unaddressed, and to fester. It’s the drug war, not the race war. It’s a problem with the educational system, not a cultural divide. Crime stats have nothing to do with color. Given a good rhetorician, we can talk around this for hours, days, years and avoid ever discussing the issue which Mr. Roof just dumped into our living rooms in the one color we all share without any possibility of quibbling—red.

We’ve had a century or more of practice dissembling over a related issue which is also now getting an airing that is long overdue. The Confederate flag. And likewise there are those trying to excuse it—that there never was a single flag for the entire Confederacy is in no way the issue, because generations of Lost Cause romantics thought there was and acted as if that were the case, using Lee’s battleflag to represent their conception of the South and the whole Gone With The Wind æsthetic. We’ve been exercising that issue in our history since it happened, with even people who thought the North was right bowing the sophistry that the Civil War was not about slavery.

Lincoln steadfastly refused to accept a retributive agenda because he knew, must have known, that punishment would only entrench the very thing the country had to be done with. He did not live to see his convictions survive the reality of Reconstruction.

So we entered this discussion about the use of a word and its power to hurt and its place in art. My own personal belief is that art, to be worthwhile at all, must be the place where the unsayable can be said, the unthinkable broached, the unpalatable examined, and the unseeable shown. People who strive for the word under consideration to be expunged from a book, like, say, Huckleberry Finn, misunderstand this essential function of art.

For the word to lose valence in society, in public, in interactions both personal and political, it is not enough to simply ban it from use. The reasons it has what potency it does must be worked through and our own selves examined for the nerves so jangled by its utterance. That requires something many of us seem either unwilling or unable to do—reassess our inner selves, continually. Examine what makes us respond to the world. Socrates’ charge to live a life worth living is not a mere academic exercise but a radical act of self-reconstruction, sometimes on a daily basis.

Which requires that we pay attention and stop making excuses for the things we just don’t want to deal with.

Confession time. I have never assumed that I am a good writer. I have never taken the position that I know what I’m doing, that I deserve respect, or that I am in any way special as a writer. My default sense of self is that I’m still trying, still learning, still reaching, and I haven’t “got there” yet. If, therefore, I write something that touches a reader, that evokes a positive response, that, given the opportunity, causes them to tell me how much they liked that story or novel of mine they read, I am always surprised and quietly pleased and a bit more hopeful that one of these days I might fully allow myself to acknowledge my own talent.

But I never let myself believe I deserve anything like that. Ever.

Initially, this came out of an inborn reticence characteristic of the fatally shy and an aversion to being the center of anyone’s attention. But you grow out of that eventually, or at least I did, because you come to realize you have nothing special about which to be shy. Also, that shyness is detrimental to your happiness when it causes you to pass up opportunities you might desperately want to embrace. It’s replaced, then, by a gradual sense of politesse, of what you might consider good manners, and a deep desire to be liked. Braggards are generally not liked, so you hide your light so you don’t become That Guy.

Too early success can derail your journey to becoming someone you might wish to be by replacing a perfectly natural humility with the idea that, hey, you really are something special! Nastiness can ensue.

I am very aware of my potential for being That Guy, the boor, the boaster, the “all about me” asshole. Part of me wants to be all of that, or at least have all the attention that leads to that. Why else would I have always been involved in work that has such a public aspect? Art, music, theater (very briefly), and writing. All of it has a Dig Me facet, especially if you have any ambition to make a living at any of it. You have to put the work out there, you have to take credit, you’re the one people have to identify with something they like in order for you to get paid. It’s all a recipe for assholedom, because you can so easily believe the hype that comes with success, and start acting like you deserve it all.

You don’t. You’ve earned it, perhaps, but you don’t deserve it.

If you don’t see the difference, then try harder. Deserving something in this instance implies believing it’s your due, regardless. Just by existing in the world, certain accommodations ought to accrue, whether you have done the work or not. We do have a category of things which fit that description—they’re called rights and everyone deserves them, they are not commodities to be dolled out according to some kind of intrinsic worth meter that suggests some people are better or more important than others. For the special stuff, we work and earn regard. It’s not “due” us by virtue of who we are.

But even in that, it’s not necessarily we who merit the regard but the work. If it has our name on it, then we get to accept the award when it’s handed out, but it’s the work that’s being honored.

We are in no way in charge of that process.

This is hard, I admit. How is the work to be separated from the one who does it? You can’t do it, really, but that’s not the point. The point is how what you put into the world impacts others and creates a space wherein honor and respect are given and received. It’s a condition of regard, one that acknowledges distinctions, sometimes fine ones, in which the work may well deserve an honor but, if given, the creator can only be said to have earned it.

That’s a negotiation and depends entirely on the relationship between creator and audience.

That Guy forgets or never understands that the relationship is what matters here. That in fact when respect and honor are given, it must be returned. Without that relationship, that process, there is no honor and awards are empty gestures.

So, all by accident, because I arrived here without a clear intent, I confess that I have never felt myself to be deserving of special consideration. I don’t think of myself as a good writer, even though I would very much like to be and hope that maybe I am. When one of my stories (or photographs or a musical performance) is praised, I am always surprised—and pleased—because it’s always unexpected.

It’s possible that, in terms of career, I have this all bassackwards, that I really ought to be pushing myself on people and, in the absence of praise, making scenes and telling people how ignorant or biased they are because they don’t like my work. Maybe I should be actively campaigning for honors, prodding, coaxing, cajoling, hard-selling myself and insisting on my worth, letting people know that I deserve something which they seem to be denying me. My sales might go up.

But I’d be That Guy and I don’t want to live with him.

One of the givens I practice in my dealings with readers is to never ask what they thought of the story. Never. That invites the potential for embarrassment. You put them on the spot and you open yourself for criticism. The common solution to that awkward exchange is dissimulation. Certainly honesty is unlikely and perhaps unwelcome. Never ask. If the praise is not forthcoming without prompt, leave it alone. Asking is fraught with pitfalls, the first of which is that comparisons are inevitably made. Praise, like all courtesies, cannot be demanded, even politely, because the expectation subverts it.

And you then become That Guy.

Especially if you ask in public.

I’m being circumspect in this. I trust some folks will understand what this is, in part, about. For everyone else, let it be the confession offered above, an explanation and description of one of the peculiarities of trying to be an artist in a public practice, a peak inside, as it were.

I never think of myself as a good writer. And I hope I’m not That Guy.

Thank you for your time and attention.

I’m in “talks” with a publisher. Cool things may be in the offing soon. Details when things are more concrete. Will this be career-changing? Who knows? It will, to be sure, take me another step on the way. It will not, at this point, be life changing.

Change is one of those terms we bandy about almost like an incantation. “Things will change” “If you don’t like it, change it” “Change is good for you” “changes are coming” and then there is the most puzzlingly problematic corollary, “Things will never be the same again.”

I’ve never understood that phrase, not in any concrete way. I know what it is supposed to mean, but in that specific sense, the question that rarely gets asked is “What things were these that were always the same in the first place?” Because in many small but no less real ways, just waking up in the morning brings you a life that isn’t the same anymore, even though it bears striking similarities to the one you had the day before.

Or put it in a slightly larger context, the oft-remarked “History changed with that event.” You really have to step back and asked “How? It wasn’t history yet when it happened, so how could it change before it was?” I mean, History changing….again, I know what it’s intended to mean, but it’s also sloppy in that it assumes history had an expected direction before said event.

Which it didn’t, really. That’s telec thinking, which humans love to indulge and which is almost always wrong.

Back to the first instance, though. “Things will never be the same” is incantatory in that it masks a hope. If change is good—or at least necessary—then you don’t want things to be the same all the way to the end.

Unfortunately, we seem to live with a profound inertia that often imposes a suffocating sameness day to day.

Perversely, we can become victim to this by embracing an impossible nostalgia, by turning our backs on the possibilities of change, and wishing for things “the way they used to be.” Too often, this involves a highly edited version of those times, with some additions and revisions that tidy up the less pleasant realities we endured, and turning them into a Camelot to which we cannot return. Mainly because, in significant ways, we were never there.

But if the prospect of changing into something unknown is too daunting, people can let this little capsule fantasy swallow them up. They live inside a constrained and ever more false set of memorative tableaux as though in a castle under siege. Should the walls ever come down, they can be left defenseless and naked, surrounded by realities made more frightening because they never bothered to understand them.

We only have one path—forward. No matter what all the gurus and wise-beings have said about pathways, all them share this in common. Tomorrow is our next stop. We can arrive at the station with anticipation, an open heart, and curious mind, or try to stay in the back of the car when the doors open and ignore what’s out there. But we will go forward. No other direction is possible.

That can get very frustrating, even if you do want to find out what’s out there. It’d be nice to stop at one of these stations occasionally and stay a while, recover a bit, rest up.

No such luck. The only thing we can do is try to travel in company with good people who will share the weight and join in the marvelment at the next stop.

They aren’t always the same folks, from one stop to the next. And sometimes people who’ve been along with you for years may, for a variety of reasons, drop away.

A pity, sometimes. Things will never be the same without them.

But then, they weren’t going to be anyway.

Just some musings for a rainy Saturday.

It seems longer, but it’s only been a bit over a month since my surgery. Everything, according to the People Who Know, has been going well. The last couple of weeks I’ve been encumbered with a brace, which is intended to keep me from moving my arm in a manner likely to impede healing. It’s been awkward.

But this, too, will soon end. According to Patrick, my physical therapist, I’m tracking the way I should be—even a bit better than expected (for age, injury, disposition)—and he estimates the brace can come off after May 8th. I’ll still have therapy to go through and it will be a few months before I’m battling superfoes and lifting cases of books, but I will at least be able to scratch my nose, comb my hair, and eat my meals with my right hand. It’s the small things one misses most, mainly because you never think about them until you can’t do them.

So I have that to look forward to. I’m wondering now if I should use this shot as my official author photo or something…

It’s still awkward to do this. My right arm is bound in an articulated brace that bears a resemblance to some kind of robotic prosthesis. This one, however, is only intended to constrain my movements so I don’t damage the surgery while it heals. Makes typing difficult, but it’s getting easier. My handwriting, already questionable, is another matter.

So back in August I had an accident. I could characterize it as an act of stupidity, but that’s not really true. I did something I had done before and had no reason to think I couldn’t do again. However, my right biceps tendon chose to give and I experienced a partial tear. Not enough to incapacitate me but enough to give me chronic problems. When it became evident that it wasn’t healing, I sought advice and went to a specialist. I saw Dr. George Paletta. One MRI and a lot of conversation later, I agreed to surgery to repair the tendon.

So on March 31st I went to a small surgery where Dr. Paletta opened a small incision on the inside of my elbow, “completed” the tear, and bolted the tendon back in place. I spent the next two weeks in a full cast.  Much reading and watching of movies ensued. Learning to do with just my left hand proved an education.

Much reading and watching of movies ensued. Learning to do with just my left hand proved an education.

Removal of the cast occasioned one of the worst pains I have ever experienced. My forearm felt as though the Incredible Hulk had grabbed it and determined to crush it. When my eyes once more focused and the spots stopped dancing, the staff, including Dr. Paletta, were standing around me smiling. “Perfectly normal,” they told me. Okay.

So now I’m doing physical therapy twice a week and slowly, slowly reacquiring the use of my right hand. I can drive, I’ve been back to work, and I’m doing this. Because the brace is a restraint on range of motion, I can’t yet brush my teeth with my dominant hand. Or eat with it. Or scratch my nose, comb my hair, etc, you get the idea. Next week I may get a bit more range. I haven’t tried playing piano and I’m not even getting near a guitar with this aluminum thing.

Before the surgery I managed to finish the 1st draft of a new novel. I’ve been noodling on a couple of short stories lately and still reading. (I’ve decided to start Agatha Christie. Read some of her books as a teenager, but that was almost half a century ago, so…) I’m working my way through a book by Kip Thorne about wormholes and such.

My hope is that by the end of May I’ll be more or less mobile again. My gym kindly put my membership on hold till such time as I can come back, but that may be even longer. I’m feeling…puffy. But if I’m careful, which I intend to be, I’ll be good as new by fall.

Meantime, I thought I’d just give folks an update. More words are coming, trust me. But lastly I want to say Thank You to everyone involved in this. People have been terrific. From my coworkers to the medical personnel, everyone has been generous, supportive, and tolerant. Thank you all.

This is almost too painful. The volume of wordage created over this Sad Puppies* thing is heading toward the Tolstoyan. Reasonableness will not avail. It’s past that simply because reasonableness is not suited to what has amounted to a schoolyard snit, instigated by a group feeling it’s “their turn” at dodge ball and annoyed that no one will pass them the ball.

Questions of “who owns the Hugo?” are largely beside the point, because until this it was never part of the gestalt of the Hugo. It was a silly, technical question that had little to do with the aura around the award. (As a question of legalism, the Hugo is “owned” by the World Science Fiction Society, which runs the world SF conventions. But that’s not what the question intends to mean.)

Previously, I’ve noted that any such contest that purports to select The Best of anything is automatically suspect because so much of it involves personal taste. Even more, in this instance, involves print run and sales. One more layer has to do with those willing to put down coin to support or attend a given worldcon. So many factors having nothing to do with a specific work are at play that we end up with a Brownian flux of often competing factors which pretty much make the charge that any given group has the power to predetermine winners absurd.

That is, until now.

Proving that anything not already overly organized can be gamed, one group has managed to create the very thing they have been claiming already existed. The outrage now being expressed at the results might seem to echo back their own anger at their claimed exclusion, but in this case the evidence is strong that some kind of fix has been made. Six slots taken by one author published by one house, with a few other slots from that same house, a house owned by someone who has been very vocal about his intentions to do just this? Ample proof that such a thing can be done, but evidence that it had been done before? No, not really.

Here’s where we all find ourselves in unpleasant waters. If the past charges are to be believed, then the evidence offered was in the stories and novels nominated. That has been the repeated claim, that “certain” kinds of work are blocked while certain “other” kinds of work get preferential treatment, on ideological grounds. What grounds? Why, the liberal/left/socialist agenda opposed to conservatism, with works of a conservative bent by outspoken or clearly conservative authors banished from consideration in favor of work with a social justice flavor. Obviously this is an exclusion based solely on ideology and has nothing to do with the quality of the work in question. In order to refute this, now, one finds oneself in the uncomfortable position of having to pass judgment on quality and name names.

Yes, this more or less is the result of any awards competition anyway. The winners are presumed to possess more quality than the others. But in the context of a contest, no one has to come out and state the reason “X” by so-and-so didn’t win (because it, perhaps, lacked the quality being rewarded). We can—rightly—presume others to be more or less as good, the actual winners rising above as a consequence of individual taste, and we can presume many more occupy positions on a spectrum. We don’t have to single anyone out for denigration because the contest isn’t about The Worst but The Best.

But claiming The Best has been so named based on other criteria than quality (and popularity) demands comparisons and then it gets personal in a different, unfortunate, way.

This is what critics are supposed to do—not fans.

In order to back their claims of exclusion, exactly this was offered—certain stories were held up as examples of “what’s wrong with SF” and ridiculed. Names were named, work was denigrated. “If this is the kind of work that’s winning Hugos, then obviously the awards are fixed.” As if such works could not possibly be held in esteem for any other reason than that they meet some ideological litmus test.

Which means, one could infer, that works meeting a different ideological litmus test are being ignored because of ideology. It couldn’t possibly be due to any other factor.

And here’s where the ugly comes in, because in order to demonstrate that other factors have kept certain works from consideration you have to start examining those works by criteria which, done thoroughly, can only be hurtful. Unnecessarily if such works have an audience and meet a demand.

For the past few years organized efforts to make this argument have churned the punchbowl, just below the surface. This year it erupted into clear action. The defense has been that all that was intended was for the pool of voters to be widened, be “more inclusive.” There is no doubt this is a good thing, but if you already know what kind of inclusiveness you want—and by extension what kind of inclusiveness you don’t want, either because you believe there is already excess representation of certain factions or because you believe that certain factions may be toxic to your goal—then your efforts will end up narrowing the channel by which new voices are brought in and possibly creating a singleminded advocacy group that will vote an ideological line. In any case, their reason for being there will be in order to prevent Them from keeping You from some self-perceived due. This is kind of an inevitability initially because the impetus for such action is to change the paradigm. Over time, this increased pool will diversify just because of the dynamics within the pool, but in these early days the goal is not to increase diversity but to effect a change in taste. What success will look like is predetermined, implicitly at least, and the nature of the campaign is aimed at that.

It’s not that quality isn’t a consideration but it is no longer explicitly the chief consideration. It can’t be, because the nature of the change is based on type not expression.

Now there is another problem, because someone has pissed in the punchbowl. It’s one of the dangers of starting down such a path to change paradigms through organized activism, that at some point someone will come along and use the channels you’ve set up for purposes other than you intended. It’s unfortunate and once it happens you have a mess nearly impossible to fix, because now no one wants to drink out of that bowl, on either side.

Well, that’s not entirely true. There will be those who belly up to the stand and dip readily into it and drink. These are people who thrive on toxicity and think as long as they get to drink from the bowl it doesn’t matter who else does or wants to. In fact, the fewer who do the better, because that means the punch is ideally suited to just them. It’s not about what’s in the bowl but the act of drinking. Perhaps they assume it’s supposed to taste that way but more likely they believe the punch has already been contaminated by a different flavor of piss, so it was never going to be “just” punch. They will fail to understand that those not drinking are refraining not because they don’t like punch but because someone pissed in the bowl.

As to the nature of the works held up as examples of what has been “wrong” with SF…

Science fiction is by its nature a progressive form. It cannot be otherwise unless its fundamental telos is denied. Which means it has always been in dialogue with the world as it is. The idea that social messaging is somehow an unnatural or unwanted element in SF is absurd on its face. This is why for decades the works extolled as the best, as the most representative of science fiction as an art form have been aggressively antagonistic toward status quo defenses and defiantly optimistic that we can do better, both scientifically and culturally. The best stories have been by definition social message stories. Not preachments, certainly, but that’s where the art comes in. Because a writer—any writer—has an artisitic obligation, a commitment to truth, and you don’t achieve that through strident or overt didacticism. That said, not liking the specific message in any story is irrelevant because SF has also been one of the most discursive and self-critical genres, constantly in dialogue with itself and with the world. We have improved the stories by writing antiphonally. You don’t like the message in a given story, write one that argues with it. Don’t try to win points by complaining that the message is somehow wrong and readers don’t realize it because they keep giving such stories awards.

Above all, though, if you don’t win any awards, be gracious about it, at least in public. Even if people agree with you that you maybe deserved one, that sympathy erodes in the bitter wind of performance whining.

______________________________________________________________________________________

*I will not go into the quite lengthy minutiae of this group, but let me post a link here to a piece by Eric Flint that covers much of this and goes into a first class analysis of the current situation. I pick Eric because he is a Baen author—a paradoxical one, to hear some people talk—and because of his involvement in the field as an editor as well as a writer.

A bit of nostalgia. Reminiscing on happy times. I’ve been pretty fortunate. I think there’ve been more smiles than frowns.

Even when the ground has been covered with nasty white snowy stuff, which is not my favorite thing anymore. But, you know, the fact is I don’t really like being in a bad mood. I very much prefer being happy, or at least content, and I suspect I’ve had more of that than the alternative.

So going through some old negatives this past week or so I found a couple of images I’d forgotten about, but which, once seen, brought back the whole day on which they were taken. Good days.

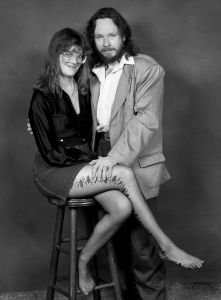

This one, for instance, was ostensibly for possible author photo use. Never used any of them for that, but Donna and I had fun taking them.

And then there’s this one, which is of us . A studio portrait, done at Shaw Camera in about 1986 or so. Me and my sweetie.

. A studio portrait, done at Shaw Camera in about 1986 or so. Me and my sweetie.

Which she still is. Soon—this weekend, in fact—it will be 35 years since our fist date.

35 Years.

For a guy who once thought he’d spend his life as a bachelor due to an inability to have a relationship, this comes as no small surprise. But you should never second-guess yourself. Or third-guess. Whatever.

35 years ago I took Donna out on our first date. I took her to see 2001: A Space Odyssey, which was playing at a theater that no longer exists. Afterward we went to a nearby Chinese restaurant which also no longer exists. In fact, pretty much the only thing that still exists, albeit in much altered form, from when we met is the McDonald’s where we met, on Kingshighway.

Look at that picture. Am I not fortunate? I’m still amazed by her. She has made my life worth having.

Damn. 35 years….

He was, ultimately, the heart and soul of the whole thing. The core and moral conscience of the congeries that was Star Trek. Mr. Spock was what the entire thing was about. That’s why they could never leave him alone, set him aside, get beyond him. Even when he wasn’t on screen and really could be nowhere near the given story, there was something of him. They kept trying to duplicate him—Data, Seven-of-Nine, Dax, others—but the best they could do was borrow from the character.

I Am Not Spock came out in 1975. It was an attempt to explain the differences between the character and the actor portraying him. It engendered another memoir later entitled I Am Spock which addressed some of the misconceptions created by the first. The point, really, was that the character Spock was a creation of many, but the fact is that character would not exist without the one ingredient more important than the rest—Leonard Nimoy.

I was 12 when Star Trek appeared on the air. It is very difficult now to convey to people who have subsequently only seen the show in syndication what it meant to someone like me. I was a proto-SF geek. I loved the stuff, read what I could, but not in any rigorous way, and my material was opportunistic at best. I was pretty much alone in my fascination. My parents worried over my “obsessions” with it and doubtless expected the worst. I really had no one with whom to share it. I got teased at school about it, no one else read it, even my comics of choice ran counter to the main. All there was on television were movie re-runs and sophomoric kids’ shows. Yes, I watched Lost In Space, but probably like so many others I did so out of desperation, because there wasn’t anything else on! Oh, we had The Twilight Zone and then The Outer Limits, but, in spite of the excellence of individual episodes, they just weren’t quite sufficient. Too much of it was set in the mundane world, the world you could step out your front door and see for yourself. Rarely did it Go Boldly Where No One Had Gone Before in the way that Star Trek did.

Presentation can be everything. It had little to do with the internal logic of the show or the plots or the science, even. It had to do with the serious treatment given to the idea of it. The adult treatment. Attitude. Star Trek possessed and exuded attitude consistent with the wishes of the people who watched it and became devoted to it. We rarely saw “The Federation” it was just a label for something which that attitude convinced us was real, for the duration of the show. The expanding hegemony of human colonies, the expanse of alien cultures—the rather threadbare appearance of some of the artifacts of these things on their own would have been insufficient to carry the conviction that these things were really there. It was the approach, the aesthetic tone, the underlying investment of the actors in what they were portraying that did that. No, it didn’t hurt that they boasted some of the best special effects on television at that time, but even those couldn’t have done what the life-force of the people making it managed.

And Spock was the one consistent on-going absolutely essential aspect that weekly brought the reality of all that unseen background to the fore and made it real. There’s a reason Leonard Nimoy started getting more fan mail than Shatner. Spock was the one element that carried the fictional truth of everything Star Trek was trying to do.

And Spock would have been nothing without the talent, the humanity, the skill, the insight, and the sympathy Leonard Nimoy brought to the character. It was, in the end, and more by accident than design, a perfect bit of casting and an excellent deployment of the possibilities of the symbol Spock came to represent.

Of all the characters from the original series, Spock has reappeared more than any other. There’s a good reason for that.

Spock was the character that got to represent the ideals being touted by the show. Spock was finally able to be the moral center of the entire thing simply by being simultaneously on the outside—he was not human—and deeply in the middle of it all—science officer, Starfleet officer, with his own often troublesome human aspect. But before all that, he was alien and he was treated respectfully and given the opportunity to be Other and show that this was something vital to our own humanity.

Take one thing, the IDIC. Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combination. It came up only a couple of times in the series, yet what a concept. Spock embodied the implications even in his trademark comment “Fascinating.” He was almost always at first fascinated. He wanted before anything else to understand. He never reacted out of blind terror. Sometimes he was on the other side of everyone else in defense of something no one seemed interested in understanding, only killing.

I’m going on about Spock because I know him. I didn’t know Mr. Nimoy, despite how much he gave of himself. I knew his work, which was always exemplary, and I can assume certain things about him by his continued affiliation with a character which, had he no sympathy for, would have left him behind to be portrayed by others long since. Instead, he kept reprising the role, and it was remarkably consistent. Spock was, throughout, a positive conscience.

On the side of science. I can think of no other character who so thoroughly exemplified rational morality. Spock had no gods, only ideals. He lived by no commandments, only morality. His ongoing championing of logic as the highest goal is telling. Logic was the common agon between Spock and McCoy, and sometimes between Spock and Kirk. I suspect most people made the same mistake, that logic needs must be shorn of emotion. Logic, however, is about “sound reasoning and the rules which govern it.” (Oxford Companion to Philosophy) This is one reason it is so tied to mathematics. But consider the character and then consider the philosophy. Spock is the one who seeks to understand first. Logic dictates this. Emotion is reactive and can muddy the ability to reason. Logic does not preclude emotion—obviously, since Spock has deep and committed friendships—it only sets it aside for reason to have a chance at comprehension before action. How often did Spock’s insistence on understanding prove essential to solving some problem in the show?

I suspect Leonard Nimoy himself would have been the first to argue that Spock’s devotion to logic was simply a very human ideal in the struggle to understand.

Leonard Nimoy informed the last 4 decades of the 20th Century through a science fictional representation that transcended the form. It is, I believe, a testament to his talent and intellect that the character grew, became a centerpiece for identifying the aesthetic aspects of what SF means for the culture, and by so doing became a signal element of the culture of the 21st Century.

Others can talk about his career. He worked consistently and brought the same credibility to many other roles. (I always found it interesting that one his next roles after Star Trek was on Mission: Impossible, taking the place of Martin Landau as the IM team’s master of disguise. As if to suggest that no one would pin him down into a single thing.) I watched him in many different shows, tv movies, and have caught up on some of his work prior to Star Trek (he did a Man From U.N.C.L.E. episode in which he played opposite William Shatner) and in my opinion he was a fine actor. He seems to have chosen his parts carefully, especially after he gained success and the control over his own career that came with it. But, as I say, others can talk about that. For me, it is Spock.

I feel a light has gone out of the world. Perhaps a bit hyperbolic, but…still, some people bring something into the world while they’re here that has the power to change us and make us better. Leonard Nimoy had an opportunity to do that and he did not squander it. He made a difference. We have prospered by his gifts.

I will miss him.