I know, it’s November. But this is what I found in October.

Hard upon the heals of my previous panegyric, a placeholder.

Last week Donna and I enjoined our first dinner train, the Columbia Star out of—you guessed it—Columbia, Missouri. Here’s a photograph and a promise that I will shortly be writing about it at more length. Meanwhile, have a pleasant next few days.

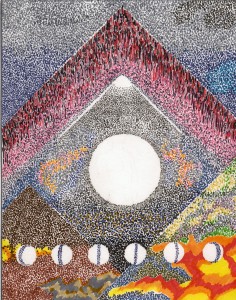

I won’t be posting for a couple of days, so I thought I would take this opportunity to put up a new image that I’m offering for sale through November.

The print will be (roughly) 11 X 14 on a 16 X 20 background, mounted on foamcore. $150.00 plus shipping and handling. Those interested, email me at info@marktiedemann.com for purchase details.

This past weekend I attended our local convention, Archon. It’s a St. Louis convention that’s not actually in St. Louis, for many reasons too convoluted to go into here, and this one was number 36. Which means, with a couple of exceptions, I’ve been going to it for three decades. (Our first con was Archon 6, which featured Stephen King as GoH, and thus was something of a media circus. I met several writers, some whose work I knew and loved, others of whom I just then became acquainted—George R.R. Martin, Robin Bailey, Charles Grant, Joe Haldeman, Warren Norwood. Some have passed away, others are still working.)

I go now to meet up with friends of long acquaintance, in whose company we have spent relatively little actual face-time, but who by now have become touchstones in our lives. It’s odd having people who feel so close that you see at most one weekend a year. Granted, the internet has helped bridge those gaps, but it’s still a curious phenomenon, one which I kind of dealt with this weekend on at least one panel.

This year, the novel that seems to have garnered the most awards was Jo Walton’s Among Others. It won both the Nebula Award and the Hugo Award, both times beating out what I considered the best science fiction novel of perhaps the last decade, China Miéville’s Embassytown. Â

Now, please don’t misunderstand—I thought Among Others was a marvelous novel. I enjoyed it thoroughly, was, in fact, delighted by it, and certainly being delighted is one of the chief pleasures of reading. I do not here intend any slight on the work.

But it took two awards that are supposed to honor the best science fiction of the year, and Among Others was barely fantasy. (One of the things I admired about it was the line Walton danced around separating the fantasy from actual occurrence and simple perception on the part of the characters.) It is in the long tradition of English boarding school stories, written as the diary of a girl who is somewhat isolated, who has run away from her mad mother (who may be a witch) after a tragic loss of her sister and a crippling accident. Living with her father now, she is placed in a boarding school where her love of science fiction is one of her chief methods of coping. The novel then chronicles the succession of books she reads over a year or two, many of which were exactly the books I was reading then and loving. It is in that sense an overview of a particular period in SF, one I found myself reliving with immense pleasure.

Embassytown, on the other hand, is solidly SF built on a very meaty idea that plays out with intensity and provokes a great deal of thought—everything SF is supposed to do. It is also marvelously well-written and to my mind was hands down the best of the year, if not, as I said, the last decade.

But it lost to the Walton.

Why?

So I proposed a panel at Archon to discuss the power of nostalgia in a field that is presumed to deal with cutting edge, next level, philosophically stimulating ideas. It’s supposed to take us new places. Granted, most of it no longer does—instead it takes us to some very familiar places (after eight decades of definably “modern” SF, how many “new” places are there really to go?) and in the last couple of decades, it’s been taking us to some very old places, alá Steampunk and alternate history. I’d never given much thought to this before as a nostalgic longing because in both cases the writers are still proposing What If? scenarios that ask questions about the nature of historical inevitability and technological destiny. The story might well be set in 1890, but it’s not “our” 1890 and we have to come to grips with the questions of why “our” 1890 has preference in the nature of human development.

But Among Others didn’t even do that. It was just a recapitulation of one fan’s love of a certain era of fiction.

Again, absolutely nothing wrong with that and I say again, Among Others is a fine novel, I unhesitatingly recommend it.

My question in the panel had to do with the potential for exhaustion in SF. Paul Kincaid talks about this here in an examination of two of the best Best of the Year anthologies, Dozois’ and Horton’s. In my own reading, I’ve noticed a resurgence of old models—planetary romance, space opera, etc (Leviathan Wakes by James S.A. Corey for instance)—where we’re seeing writers take these comfortable, familiar forms and rework them with more contemporary sensibilities, broader perspectives, certainly in many instances more skillful prose. But the “cutting edge” seems to be occupying narrower slices of the collective SF zeitgeist. (William Gibson, to my mind still one of the most interesting SF writers, has all but given up writing SF in any concrete fashion and is now doing contemporary thrillers from an SF perspective. Is this cutting edge or an admission that there simply isn’t anywhere “new” to go? Likewise with Neal Stephenson, who opted to go all the way back to the Enlightenment and rework that as SF—taking the notions of epistemology and social science and applying them to the way a period we thought we knew unfolded from a shifted perspective.)

Kincaid’s piece talks about insularity in the field, which is not a new criticism—arguably, the recent upsurge in YA in the field is a direct response to the ingrown, jargon-laden incestuousness of the field in the 80s and 90s, where it seemed that if you hadn’t been reading SF since the early Seventies you simply would not understand what was going on—but I’m wondering if a new element has been added, that of an aging collective consciousness that unwittingly longs for the supposedly fertile fields of a previous Golden Age in publishing, an age before Star Trek and Star Wars and cyberpunk, when it was easier (supposedly) to write an almost pastoral kind of science fiction and you didn’t need a degree in physics or history or cultural anthropology to find your way. (I suspect the tenacity of iconic worlds like the aforementioned Star Trek and Star Wars can be explained by a very common need for continuity and familiarity with a story that you can access as much through its fashions as its ideas.)

Having just turned 58, and feeling sometimes more behind the curve both technologically and culturally, I’m wondering if, in a small way, the accolades given to a work of almost pure nostalgia is indicative of a wish for the whole magilla to just slow down.

(The trajectory of my own work over the last 20 years is suggestive, where I can see my interests shift from cool ideas, new tech, stranger settings, into more personal fiction where the internal landscapes of my characters take more and more precedence. And many of them are feeling a bit lost and clueless in the milieus in which I set them. Not to mention that I have moved from space opera to alternative history, to more or less straight history and into contemporary…)

The panel was lively and inconclusive—as I expected, because I didn’t intend answering my own question, only sparking discussion and perhaps a degree of reflection.

SF goes through cycles, like any other art form, and we see the various subsets rise and fall in popularity. There’s so much these days that I may be missing things and getting it all wrong. The reason I brought it up this time is a response to the very public recognition of a given form that, this year, seems to have trumped what I always thought science fiction is about.

I confess, there are many days I look back to when I first discovered SF, and the impact it had on my adolescent mind (and the curious fact that when I go reread some of those books I cannot for the life of me see what it was about them that did that—no doubt I was doing most of it for myself, taking cues from the works) and when I first thought about becoming a writer. It does (falsely) seem like it would have been easier “back then” to make something in the field. Such contemplation is a trap—you can get stuck in a retrograde What If every bit as powerful as the progressive What If that is supposed to be at the core of science fiction.

This weekend I’ll be attending the local science fiction convention, Archon. I’ve only missed a couple of these since 1982, when Donna and I went to out very first SF convention, Archon 6. Stephen King was guest of honor and we got to meet many of the writers we’d been reading and enjoying, some, at least in my case, for many years. Until that year I hadn’t even known such things happened.

Science fiction for me was part of the fundamental bedrock of my life’s ambitions. Not just writing it or reading it, but in a very real sense living it. It is difficult to recapture that youthful, naïve enthusiasm for all that was the future. The vistas of spaceships, new cities, alien worlds all fed a growing æsthetic of the shapes and content of the world I wanted very much to live in.

I’ve written before of some of the aspects of my childhood and adolescence that were not especially wonderful. My love of SF came out of that, certainly, but it was altogether more positive than merely a flight response from the crap of a less than comfortable present. I really thought, through a great deal of my life, that the world was heading to a better place. I found the informing templates and ideas of that world in science fiction, in the positivist philosophy underlying so much of it.

I’ve written before of some of the aspects of my childhood and adolescence that were not especially wonderful. My love of SF came out of that, certainly, but it was altogether more positive than merely a flight response from the crap of a less than comfortable present. I really thought, through a great deal of my life, that the world was heading to a better place. I found the informing templates and ideas of that world in science fiction, in the positivist philosophy underlying so much of it.

And I liked that world!

It was not a world driven by bigotry or senseless competition for competition’s sake. It was not a world where deprivation was acceptable because of innate fatalism or entrenched greed. It was not a world that lumped people into categories according to theories of race or economics that demanded subclasses.

True, a great many of the novels and stories were about exactly those things, showing worlds where such attitudes and trends dominated. But they were always shown as examples of where not to go. You could read the paranoid bureaucratic nightmares of Philip K. Dick and know that he was telling us “Be careful, or it will turn out this way.” We could read the dystopias of a Ballard or an Aldiss and see them as warnings, as “if this goes on” parables.

True, a great many of the novels and stories were about exactly those things, showing worlds where such attitudes and trends dominated. But they were always shown as examples of where not to go. You could read the paranoid bureaucratic nightmares of Philip K. Dick and know that he was telling us “Be careful, or it will turn out this way.” We could read the dystopias of a Ballard or an Aldiss and see them as warnings, as “if this goes on” parables.

You could also read Ursula Le Guin and see the possibilities of alternative pathways. You could read Poul Anderson and see the magnificent civilization we might build. You could read Clarke and glean some idea of how people could become more than themselves.

You could see the future.

And what did that future offer? By the time I was eighteen I knew I wanted to live in a world in which we are all taken as who we are, humans beings, and nothing offered to one group was denied another just because. I recognized that men and women are equals, that our dreams and ambitions are not expanded or diminished by virtue of gender. I understood that building is always more important than tearing down. I discovered that Going There was vital and that the obstacles to it were minor, transitory things that sometimes we see as too big to surmount, but which are always surmountable.

Sure, these are lessons that are drawn from philosophy and science and ethics. You can get to them by many paths. I just happened to have gotten to them through science fiction.

I envisioned a world wherein people can engage and interact with each other fearlessly, without arbitrary barriers, and we can all be as much as we wish to be, in whatever way we wish to be it.

So imagine my disappointment as I watch the world veer sharply in so many ways from that future. A world where people with no imagination, avaricious or power hungry, people of truncated and stunted souls are gaining ground and closing those doors.

So imagine my disappointment as I watch the world veer sharply in so many ways from that future. A world where people with no imagination, avaricious or power hungry, people of truncated and stunted souls are gaining ground and closing those doors.

There is a girl in Pakistan who may yet die. She’s 14 years old and she was shot by the Taliban because she dared to stand against them. She assumed her right to go to school, something the Taliban refuse to accept—females should not go to school—and rather than engage her ideas they shot her to silence her.

In our own country we have men in places of power who think women shouldn’t have the right to control their own bodies, others who opine that maybe slavery wasn’t so bad after all, others who deny the legitimacy of science because it contradicts their wishes and prejudices.

In our own country we have men in places of power who think women shouldn’t have the right to control their own bodies, others who opine that maybe slavery wasn’t so bad after all, others who deny the legitimacy of science because it contradicts their wishes and prejudices.

This is not the world I imagined. Why would any sane person deny anyone the right to an education? How could the community around this girl even tacitly support this idea? This is so utterly alien to me that it is incomprehensible. This is evil. This is not the world of tomorrow, but some kind of limpet world, hermetically sealed inside its own seething ignorance that, like a tumor, threatens everything that I, for one, believe is worth while.

So I write. I write stories and I write this blog and I write reviews and I write and I talk and I argue. It is disheartening to me how many people use their ignorance as a barrier to possibility, to change, to hope. I can’t help sometimes but think that they would have benefited in their childhood from more science fiction.

I still have hope. It still comes from the source well of my childhood imagination, that we can build a better world. If that’s naïve, well, so be it. Harsh reality, unmitigated by dreams of beauty and wonder, makes brutes of us all.

See you at Archon?

“Do you expect me to talk?”

“No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die!”

The exchange between Bond and Goldfinger may sum up the attitude of many who are tired, offended, or otherwise ambivalent or disinterested in the absurdly long career of the improbable James Bond, 007. Even those of us who have been more or less unable to let go our adolescent attachment to the character have doubtless wondered why he hasn’t just died.

He should have, certainly after the criminal treatment he endured toward the middle and end of the Roger Moore years. All due respect to Mr. Moore (he didn’t write the films, he had probably less control than most leading men), I for one never quite accepted him as Bond. He was always a bit too pretty, a bit too sophisticated, a bit too…light.

But the movies were popular, he kept signing on, and we endured, waiting for the next incarnation of Sean Connery.

The iconic Bond image of Connery with the long-barreled Walther (yes, that thing was a Walther, but it was an air gun because the actual prop hadn’t arrived for the photo shoot) which was never seen in any of the Bond films is not the one that summed up the character for me. Rather it was this one:

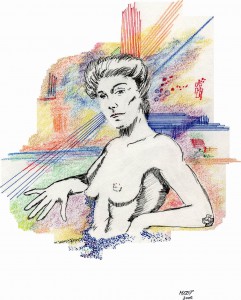

The first real good look at Bond, at the L’Circle club at the beginning of Doctor No. This is the image that made me want to be Bond— utterly unconcerned, cool, detached, and completely confident within himself. He’s playing a fairly expensive game of bacarat and he obviously could care less whether he wins or loses. (Of course, this is not true—Bond always cared about that, but not over trivial things. The trivial things simple fell in line when he walked into the room, and this was another characteristic that made him, to a clumsy, hormone-laced adolescent, such an enviable figure. How badly I wanted to simply not give a damn and how thoroughly I gave a damn about not being able to do that.)

The first real good look at Bond, at the L’Circle club at the beginning of Doctor No. This is the image that made me want to be Bond— utterly unconcerned, cool, detached, and completely confident within himself. He’s playing a fairly expensive game of bacarat and he obviously could care less whether he wins or loses. (Of course, this is not true—Bond always cared about that, but not over trivial things. The trivial things simple fell in line when he walked into the room, and this was another characteristic that made him, to a clumsy, hormone-laced adolescent, such an enviable figure. How badly I wanted to simply not give a damn and how thoroughly I gave a damn about not being able to do that.)

I saw that first Bond film on first release. I was eight at the time and it wasn’t the women that got me, it was that dangerous cool he had at his disposal. Later, as I reached puberty, the women became important, but till then it was being lethal—and not using it—that was the thing.

And dressing well and talking well and comporting yourself as if you knew why you were there and what you were doing. It was a total package that was the only viable replacement for the stoic gunslinger in the westerns. In the scope of a kid’s imagination, Bond was doable.

I wrote an essay for one of the BenBella Smartpop anthologies, James Bond In The 21st Century riffing on an imaginary history of the films, with a departure from Sean Connery. It could have happened, Fleming was not taken with Connery at first, and there were others who could have filled the role. (Fleming’s choice was David Niven, which, given the physicality of the character, is kind of absurd. But it explains the subsequent choices, I think, of actors.) It was also an alternate history of the franchise had it not been the hit that it was. It was a fun piece to write, but it addressed a serious question.

Why did a franchise that became, for a time, so massively ridiculous continue to be such a big deal?

I think the answer is in the new manifestation. Daniel Craig (and the writers) has gone back to the source in many ways and given us a Bond more in line with Fleming’s original conception of someone who is genuinely dangerous who wears a veneer of polish, culture, and civilization.

Once again, though, we harken back to that first on-screen look at Bond and see its reemergence in Craig’s portrayal. Detached, completely in control, cool, and competent.

Once again, though, we harken back to that first on-screen look at Bond and see its reemergence in Craig’s portrayal. Detached, completely in control, cool, and competent.

But with a difference for the films.

He’s vulnerable.

The last time Bond was vulnerable was in On Her Majestie’s Secret Service and Tracy Bond. After that, he was in all but the Kryptonian origin, Superman. It became the trademark. Nothing got through, not really. He had his empathy boxed up and set to one side, to be taken out on special occasions.

And there’s an appeal to that, to be sure. We have all been undone by our notoriously fickle and sabotaging emotions, made fools of, acted stupidly. What would we give to be able to avoid all that?

Well, the price is too high, but we have fantasy characters through which to pretend.

But I think it goes too far and they become so unlikely—not in their actions, the plots that give them a showcase, but in their emotional lives—that we cannot identify with them at all. All we have then are the toys, the lifestyle, the fashions, and the rollercoaster ride of an action sequence.

Craig has been allowed to open Bond up so we can reconnect, albeit in a small way, with the pathetic human being caged behind the armor. The fact that Craig is a first-rate actor (possibly better than Connery even in his prime) doesn’t hurt.

Bond has survived, though, because at his base he still represents a level of competence in a fickle, dangerous world we would all like to tap into. Bond is always centered, he always knows what he’s about and how to act on that knowledge, and that is a very attractive ideal. When you look at the first three Bond films, you can see that and a slightly vulnerable man, one who doesn’t always get it right, who can become involved, and can therefore be hurt. After Thunderball they became all about the gadgets and some surreal good vs evil drama that actually gave a good shadow-theater representation of the world at large.

The other thing that has carried us through so many really awful Bond films, though, is the myth of the uninvolved sybarite. He comes in, takes his pleasure, kills the bad guy, and leaves unscathed. He’s a moral avenger who gets to party occasionally. His reward for doing the right thing was good food, fast cars, fine clothes, and great sex. Bond never got fat, never caught a ticket or the clap, never left behind a single mom, and always looked good. In return, he saved the world. There was no sacrifice, really—he was a mercenary.

Except that’s not what Fleming wrote. And when they rebooted the franchise and chose to do Casino Royale, they put that in there. It may be ignored in subsequent films (I hope not, it’s what elevates Bond above the common), but it was there—Bond is sacrificing his soul.

That first novel, Casino Royale, was about that. Bond was a new agent, freshly-minted with a 007 license, and fully a third of the book is him in hospital, working through the emotional and moral calculus of continuing to do this ugly, brutal job. To their credit, the makers of the first Craig film kept that in. We were even, dimly, shown its conclusion in Quantum of Solace, where at the end Bond has made his choice, and put on the armor.

It will be interesting to see if they continue to keep him human, if only slightly, or if they’ll do what they did before and turn him into the Road Runner getting one over on all the coyotes on the planet.

Happy birthday, Mr. Bond.

Archon 36 is approaching and I’ve taken out a couple of panels in the art show. Consequently, I’ve been playing in order to create images suitable for a science fiction/fantasy art show. My most recent accomplishment:

I have a few others, plus a couple of actual paintings and drawings, but I’m fairly pleased with this one.

Now for the crass commercial message. This image is for sale. The one I’ll be hanging at Archon will be and you can order one directly from me. Just drop me an email, mentioning the image title (Twin Sun Pastoral) and I will reply with price and all that.

In fact, most of my visual art is available for purchase and some time in the next couple of months I’m going to be putting up another page here to feature an “image of the month” for sale.

End of commercial. As I become better acquainted with Photoshop, I’m finding ways to realize more interesting images. (I recently discovered the magic wand and it has opened up vast possibilities!) I hope you enjoy it at least.

And thank you in advance for your consideration.