Because colors dazzle and hide…and because sometimes the best colors are made by black & white…

Because colors dazzle and hide…and because sometimes the best colors are made by black & white…

Once more before the screen, on an on-and-off rainy day. I’ve been trying to follow up on the good effect of a story sale and bulling my way through some stories that have been hanging fire for too long. What do I feel like doing instead? Well, not what’s below. I don’t fish. I would be one of those who would bring a book and fall asleep, probably get sunburnt, mosquito-bit, generally overheated, and with no fish to show for it because I wouldn’t really care.

But the sunshine would be nice. And a bit of placid surroundings. Don’t know about the audience, though…

This is Coffey.

Coffey is our very good friend. Our buddy. Coffey makes sure we remember to laugh, keeps us company (especially when she can do so on the bed) and forces us to take walks.

Coffey is about 15.

Yes, that’s correct. Fifteen. She’s healthy, just very slow these days. When we grab the leash, she bounds around our feet like a puppy. She’s good for about three blocks of all-out walking, then she slows to a snail’s pace and makes up for the distance with careful study of various leaves, stalks of grass, patches of concrete, and other smells. But she still gets excited about that walk.

I haven’t posted anything about her in a while and she’s gotten a bit camera shy lately—more can’t be bothered than any kind of misplaced vanity.

If we’re careful, we’ll have her for a while yet.

But she’s 15. I’m amazed.

No plan here, just thoughts. It’s Sunday as I begin writing this, second day for me of a four-day weekend. Timing.

Lack of attention bedevils me. I have things to do, a wide variety, and I get befuddled by which I should pay most attention. It matters because I end up scattering my attention widely and so get little done in each endeavor. Some of my friends understand this, but not all.

This morning I got out of bed (I hesitate to say “awoke” because I wouldn’t classify my condition that way) and stumbled through my morning routines. Making coffee is so embedded in my brain that I think if I sleep-walked that is one of the things I would do. Donna was already up, tending to the dog. To be honest, I felt like going back to bed, but I intuited that it would only waste time. Another hour or two would not improve my ability to feel whole, just delay it. Further honesty requires me to admit that mornings like this frighten me a little, because I feel so “off” that I think something must be wrong.

I’m just tired, really. An hour or two after getting out of bed I feel pretty much as I’ve always felt. Slow but present.

I’ve had a number of conversations of late about intelligence. Genius, even. I think a genius would be internally unaware of it. My father, I sometimes feel, was a genius. Is. (Yes, he’s still alive, but now so impaired by deafness and poor sight that interaction is virtually impossible.) He never believed so. He railed about how other people seemed so stupid, how they overlooked, missed, or never figured out things which seemed so obvious to him, and he blamed laziness or prejudice or ambivalence. How could they not see? When I pointed out to him that he himself was far from ordinary, he bridled. No, that couldn’t be it. He did not see himself as a particularly smart man. But he was dogged, possessed of a degree of focus and ability to concentrate I found unachievable. His own opinion would never allow recognition of his “gifts,” if gifts they were.

I’ve been accused—recently—of being “superior.” Not a compliment.

We live in a culture that prizes knowledge only when it’s somewhere else. It’s cool when it’s on tv or in a lecture hall or, most importantly, when it makes someone a lot of money. But when it lives next door to us we resent it. When we have to talk to it every day we hate it, because it feels like someone is showing off, trying to be better than everyone else, getting off on making others feel stupid. I’ve never understood that. It’s not like all the information isn’t there for everyone to access.

It’s a choice of what we find important. As far as I’m concerned, too many people are too invested in things that don’t matter. (Is that me being judgmental? Why, yes, it is. Unapologetically. You have to choose, you have to decide. Others, I realize, level their judgment at me to the same or greater degrees. What good is that novel you just read? Isn’t that a waste of time? Well, the same could said about the goal that player just made that you reacted to orgasmically. If you’re going to judge me for having no interest in your passion, I’m going to judge you for having none in mine. Let’s lay it out and compare worth some day and see how what stacks up.)

(I have noticed that this phenomenon is not limited to intellectual pursuits. I’ve been insulted in the past for being in good physical condition. I lift weights, it shows. I’ve been treated as somehow weird by people who…well, any deviation from an assumed norm will intimidate people who just can’t seem to bring themselves to do the work to achieve something they might actually want to do. It’s as if they think they should have been born with these characteristics and when it turns out they have to do some actual work, instead of embracing the opportunities, they turn to resentment of those who do.)

I didn’t intend to complain this morning. But I have some things on my mind. This is a free-flowing post. Read at your own peril.

I made myself go to the gym this morning. I halfway expected to be unable to finish a workout. Instead, as often happens, about half to two-thirds through, I felt better. Blood flowing, I came awake.

And on the drive home I started having conversations in my head.

Yes, I talk to myself. I always have. My interactions with my fellow creatures have often been frustrating to me. Things I miss, don’t get, say wrong, hear wrong, respond inappropriately. A good deal of what people see today is a carefully constructed façade designed to offer an interface that works in group settings. Not fake, no, but selective and practiced. At one time I did try putting a fake front up and it never worked. It took a long time for me to realize that, though, because part of the front was a very selective filter that kept useful interaction out.

(That annoying piece of advice, so often given, to just “be yourself” used to infuriate me. Firstly, how the hell does one do that? I mean, really. First it assumes you know who you are. Second it assumes that you have a choice about how you come across to other people. You do, as it turns out, but it rarely comes automatically. And thirdly, it fails to take into account whether or not you like who you may be as “yourself.” Don’t people realize that “being yourself” may well be the last thing you want to be because you find whatever that is to be…wanting? Of course they do, they’ve been having the same struggle, but probably don’t realize it. All those “popular” people, do we really believe that’s who they really are? If you could look inside to see, would it be what you see on the outside? No. So, stupid advice, well-meant, but as often as not self-defensive.)

I’m sitting here in my office, trying to rework a short story that has resisted conclusion for months. Like most of my short stories in the last several years, it seemed promising because I had a very cool idea. The idea remains cool. Getting it across as a compelling story is another matter. And, as usual, I am procrastinating by working on this post instead.

I’m listening to Walter Piston. He was an American composer, mid-20th Century. I stumbled on him during one of my periods of exploring obscure classical music. You can listen to him and hear a bit less experimental version of Barber and Copland and maybe Hanson. (Again, who? Yeah.) I’ve got a few CDs of his symphonies. They make excellent background for writing, but when you really listen to them you hear a familiar strain of anxiety that seems a part of most American neoclassical. You listen to Copland and the others and you can hear a boldness, a brashness that seems distinctly American. But along the way, especially in the symphonies, comes a stretch of uncertainty. I call it anxiety. The anxiety of not being so sure of yourself, perhaps, or the anxiety of knowing you have a lot of responsibility and can’t really carry it. (I sometimes think Ives, whom I cannot really stand, was about nothing but that uncertainty.)

The best science fiction carries that anxiety in its guts. We’re boldly going where we don’t belong and nervous about it, but eager. so eager to see the next neat thing.

So I get home, muscles still humming from a decent workout, brain filled with a silent conversation about an unresolved issue, and Donna is still doing landscaping in the back yard. I help by moving some heavy stones, then retreat inside, eventually migrate down to the office, and start riffing on these stray thoughts.

Most days, lately, I write a few sentences, correct some errors, tweak. Then I scoot to the other computer and cruise. Yesterday I listened to a report on “downgrading” humans, which talked about how the information explosion has been coopted by the so-called Attention Economy to the detriment of actual intellection.

Downgrading Humans. According to the report, our brains are not equipped to deal with the information deluge constantly poured through them. We get overwhelmed, the tools we have to sort wheat from chaff are inadequate, we can’t tell noise from signal after a while, and soon we’re just clicking through from one bit to the next in a parody of research. The limitation offends, I’m sure. I’m resentful of my inabilities, especially when it comes to knowledge. But it’s an academic kind of resentment now that rarely obtrudes into the kind of seething animosity a teenager might feel when being told no. It’s more frustration now when I run against my own lack of information and ignorance when I’m in the middle of a project or a conversation.

The problem I imagine with what is being described as “downgrading” is that indulging the immersion in click-throughs can come to feel like genuine learning.

Plus, there’s something addictive about. The dazzle of bright, shiny objects.

There’s a big market for self-help books. A lot of them are practical, how to do things, but a lot of them are about changing your life, becoming a new or different or better person. Many border on genuine psychology, but most seem to be manuals for self-improvement that only glance off the deeper aspects of who we are. Years ago, groping toward some kind of self-knowledge, I read a lot of them. Fritz Perls, Leo Buscaglia, Eric Fromm, others. I gleaned useful things from them all, but it seemed as I grew older, less and less of what I read in these books offered anything truly useful. Reality never conforms to neat paragraphs of “if this, then do that.” But occasionally there was genuine insight. I stopped reading them after I shifted into philosophy. But there’s a huge market. You would think we live in a world of remarkably healthy self-actualized people. I have no idea, but I have come to believe that most of these books sell to people who believe that all they have to do is read them and that is sufficient. Acting on the advice? Well.

I’ve taken a hard look at my own habits. I’ve become craggier in some ways. The state of the world has a bit to do with this, but in general I’ve been dissatisfied with my own progress along various fronts. I wondered, after hearing about this phenomenon, if I were a victim of this. Turning to the very thing that is largely the source of the problem is an irony past stating, but it is true that even though an overwhelming amount of dross permeates the internet, there is much that is worthwhile. A degree of ordinary scepticism is required and some robust filters, but you can find out useful things. So I did a bit of research on internet trends and realized quickly that I am a weekend tourist at worst. This thing distracts me, but I spend far more time reading books than ever I spend online.

But the distraction is enough to derail my concentration. It’s worse when I’m not working on a specific project. The discipline of the project keeps me focused.

Of course, then there are the days when my hindbrain cries out for relaxation. For what Donna calls “vegging.” One of the things my parents, worrying all through my upbringing that they would fail to implant it, managed to instill is an ethic that demands I waste no time. So even the things I do for “relaxation” seem to require a practical reason, a purpose. I’ve invented a number of excuses to fool my subconscious so it will leave me alone when I’m indulging the “frivolous.” I wish I could just…

I listen to music to put me in moods. Moods to write, to read sometimes, to work out. Music is a deep pool of inspiration and replenishment for my soul. We live in an age where the available sounds are greater than at any time. The possibilities are amazing. I hear better performances, more intriguing compositions, wilder explorations today than ever before, in just about any genre of music you care to name. You would think we could find a common soundtrack with all this to choose from, but the click-through ethic renders too many too impatient to sit and truly listen.

Or does it? That same volume of data may just serve to lend cover to large groups of people who do exactly that—sit and listen. They don’t answer surveys, they don’t buy in predictable manners, they don’t feed the pop machinery. It may be that we’re about to hear from them in a Big Way. I have noticed a lot of young people buying more books, books you might not predict they would buy. And of course the books being published…I can’t say that they are “downgraded.” No more than they ever were. And the best is better than ever before.

I take my optimism where I can find it.

Among the things I want to do before I’m gone: publish a dozen more books, record and release an album of original music, mount a couple of exhibits and possibly publish a monograph of my photographs, and maybe start drawing and painting again. State like that it would seem I need another lifetime. One thing I’ve come to appreciate (though perhaps not experienced yet) is that a lifetime doesn’t have a specific time limit and you can have more than one, overlapping or contiguously.

We’ll see what can be done with that.

Thank you for indulging me.

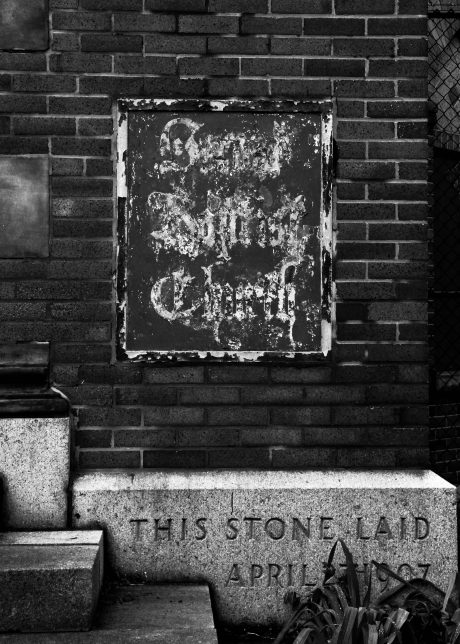

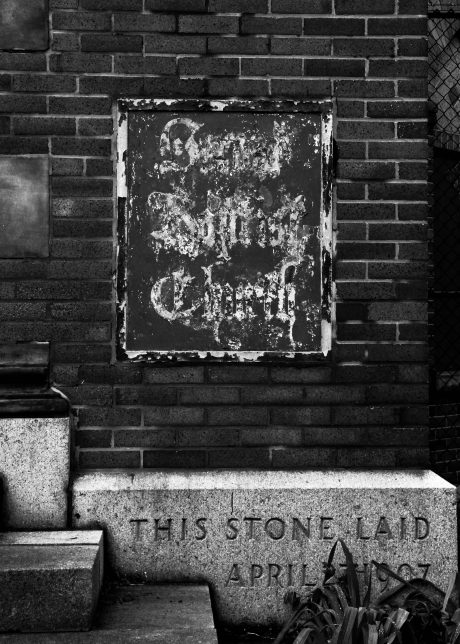

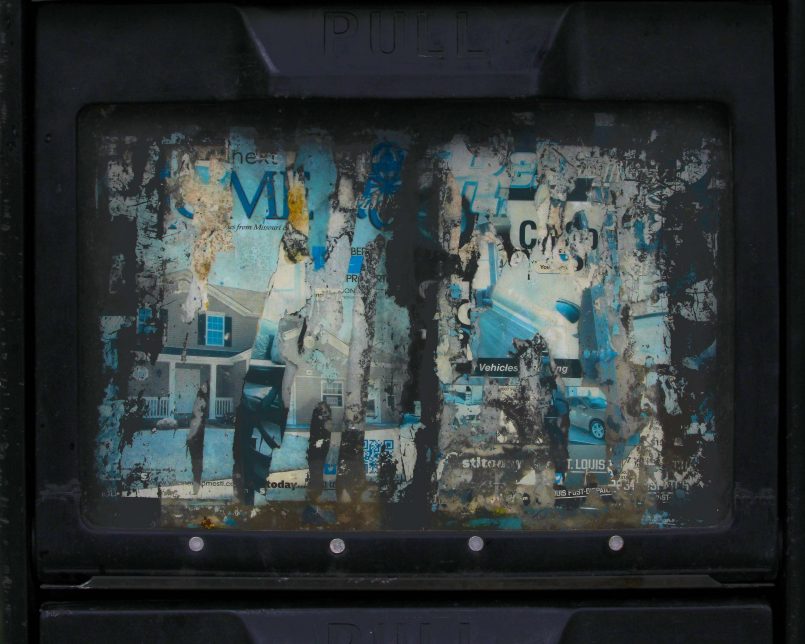

I did a short walk-around not long ago and made photographs. I haven’t had time to do anything with them till now, so…

Take them as metaphor, as studies in texture, as current commentary. Or just as interesting images.

I’ve been having difficulties for the past several months with this posting window. First I couldn’t load images, then for some reason the entire composing window vanished. I ended up having to back-door my posts through my other blog. This morning, though, I boot up to find an update that has, apparently, resolved the issues. Â (Knock on digital wood.) Sometimes, it seems, just waiting, biding one’s time, leaving well enough alone…

In any case, allow to leave an image while I bask in the readjustment of my online universe.

It’s been obvious to me for some time that I have a time management problem. I need to be working on fiction. (Right now, like while I’m doing this.) The urge to write is something every writer understands. The trouble is, the urge is sort of undifferentiated. It doesn’t care what you write, just that you do.

And it is so easy to do these things rather than chip away at the short story that currently defies completion.

Not to mention all the other pesky things that gum up the well-intentioned schedule you’ve made for a given day.

I should listen to no news. I should stay indoors, holed up with provisions for a siege, turn off my phone, never venture away from my computer until the new story is submittable.

Should and will rarely intersect.

I’ve been having technical issues with my WordPress account lately. I’m writing this by a somewhat tortured backdoor method that requires using a pathway from my other blog. I intend to use it as a good excuse to work on other things until the next major upgrade comes down the pike.

So I have not been posting as frequently as I once did and plan to continue not posting that frequently. If the world implodes, the president resigns, or glaciers begin reforming, let me know. I have fiction in the pipeline.

So, given the last week’s worth of utterly unpredictable news…something that expresses my feelings about the future.

I enjoyed a brief conversation yesterday on the subject of writing. The act of it, the discipline, the challenge. The prompt was “writing every day.” Somewhere along the way, we who do this as—well, as more than a hobby, but often less than a profession (even if we have pretensions in that direction)—receive that bit of advice: write every day. Even if it’s only a sentence.

Partly, this is a matter of discipline. Partly exercise, like working out. Mainly, though, it’s a combination of establishing a habit, so it becomes automatic, and creating a space in one’s psyche where this thing happens.

I know, that’s imprecise. Everyone has such a space, though. It’s where we store all the processes and associated tools for a task we do all the time but is in some ways apart from who we consciously are. We label it the Creative Process, among other things, but have no real handle on what exactly it is.

Where it comes from, though, is less ethereal. It comes from engagement. It comes from doing. It comes from repeatedly demanding of ourselves that something cool be produced and put into the world. As a kid hunched over a blank piece of paper, pencils and crayons at hand, trying to draw, maybe even make a comic, scrawling sometimes because there’s a shape you want to make but it just won’t appear. You don’t have the skills, not yet, just the urge (and the urgency) and some time. (Time, that intangible we have so much of at five that when we’re thirty-five has become naggingly scarce and at sixty-five is more precious than anything but love.) Some, maybe most, give up when it proves too difficult. They can’t control the pencil, they haven’t got a “knack” for it (which is a way of saying it may be a skill requiring far more time and attention than they’re willing to commit), or they can’t quite visualize what exactly they want to create. Others yield to distractions—games, media, friends who want to monopolize even that bit of time, chores, or the mine field of living a less than nurturing life—and some never feel the urge in the first place. Other things attract their obsessive attention.

When we’re children, we don’t recognize “practice” as an intentional effort to improve. We practice walking, but it doesn’t feel like that. We practice talking. We practice social intercourse. We practice reading. If we’re enjoying it, having fun, or simply doing something that seems like the thing to do, it doesn’t register as practice. Not until we consciously acknowledge that we’re trying to achieve a specific goal. Once walking and running become either sport or turn into dancing and we realize there are skill levels we need to achieve, then we understand the idea of practice.

It’s odd, then, to realize that so many people assume that when it comes to writing, expectations are different. The idea of practice comes as a shock. After all, they’ve been reading since they can remember and they’ve had to write papers through school (presumably) and all this, if done at all diligently, no longer seems like work. (Reading, especially. We don’t usually think about practice when it comes to reading, it’s something we just do, like breathing. At least some of us. And for those for whom it does not come easily, it seems never to occur to many of them that they could practice it and get better. It’s something we either do or get by without.) You see this surprise in people who attempt to write—a novel, a memoir, a history—without ever having undergone any of the preparatory work to learn how, and are then told “You don’t know to write.”

There is a point when all of us who want to be writers suffer this realization. Some less than others—there really does seem to be a “natural” facility in place for certain people, but it’s an illusion; dig deep enough you will likely find long periods when writing as practice was going on, either in journals and diaries or personal essays—but no one is born with a “gift” that allows us to produce masterful work at first attempt. We have to learn. We have to practice.

And carving out a regular space in which to do that is essential. Hence the “write every day” dictum. You do it till it becomes a habit. You get to a point where you don’t feel quite right if you don’t.

But then, once established, you practice.

When I announced my desire to become a photographer (at about age 15 or 16) my father bought me a lab, I acquired a decent camera, and then took it everywhere. What dad then did suggests he understood this concept of practice even as it applied to art: he bought me a case of film (about 250 rolls of film at that time) and told me to blaze away. When I worked my way through all that film, I knew something about photography beyond the mechanics.

Almost none of those pictures was worth a damn as art.

Ansel Adams once allowed that an artist is good in direct proportion to how much he or she has thrown away.

Learning to write is a long process where, having carved out the time and space to do so, you write. A million, two million words, which you then pretty much discard.

You can be taught grammar. You can be taught formatting (though, from some examples I’ve seen, this seems to be one of the hardest lessons to learn). You can learn many things having to do with craft (limiting adjectives, using an active voice, eliminating said-bookisms, point of view).

You cannot be taught the art, that is finding what it is you want to say and honing it to where it actually emerges from the words. This is the thing you bring to the endeavor that is yours. It cannot come from outside.

But you have to practice until it emerges.

A million, two million, three million words. The muscles ache but build, the synapses interconnect, the hidden pathways become clearer.

It can’t be taught because what I’m talking about is personal. You can be guided. It can’t become something other people might want to read in complete isolation. You write, someone reads, hands it back puzzled. Questions. Try this. Better? No, that’s not what I’m trying to say.

A million, two million…

Observation. Most visual art is observation. Look closer. Stop being overwhelmed by the distractions, the colors, the shifting shapes, the preconceptions. We see what we expect to see most of the time. Learn to filter. The artist extracts from the expected what it actually there to be seen. (I often heard from people looking at my photographs “Damn, I would never have thought to take a picture of that.” Which usually meant they would never have seen that. And even then, it was not so much the thing but the way it is presented, so that it reveals. “But what are we revealing in writing that requires that much attention?” Everything that is important. “But how can I tell?” Look closer. Write more.)

Start by making that space.

I do not write every day. Not anymore. I try, I intend to, and when I don’t I feel uneasy. But I used to, sometimes necessitating being something of an ass to the people around me. (You can tell when people don’t understand the idea of practice when it comes to writing by how many will interrupt a writer with the assumption that they aren’t actually doing anything.) Over years, the words took on heft, weight, concrete meanings. The configurations did things to readers. The descriptions became windows or doorways rather than blueprints. It happens gradually, sometimes glacially, and before you get there it can be profoundly frustrating.

“I read this and that and tried to write that way and it still doesn’t come out the way I want it to.”

Practice.

The other benefit of that million or two of discarded and buried wordage is that obscure goal of Finding Your Own Voice. Like most aphorisms about writing, it’s a tantalizing idea that says too much and too little. Those dispensing it know what it means, but those needing wisdom might not get it.

Your Own Voice, on the page, is not the voice with which you speak in everyday exchanges. Like everything else on the page, it is entirely artificial. That does not mean fake, which too often is what we hear when discussing art. We place a premium on “honesty” and “sincerity” as if that’s all we require, unconsciously (and sometimes ostentatiously) rejecting artifice as somehow impure, when in reality learning the craft and honing our art—becoming good artificers—is the only way to reach the levels of truth we seek to convey. Finding your own voice is a consequence of learning how to say what we feel and observe, and that requires skills which are learned, practiced, and built over time.

Frank Lloyd Wright joked once, when he was in his eighties, that he had designed so many buildings that he could just “shake them out of my sleeve.” He meant, of course, that he had acquired a level of craft and skill which channeled his visions as a matter of course. He had become, over decades of work, so adept that when he imagined something he could just sit down and do the technical end almost by second-nature.

The first step in reaching that level is making that space wherein the practice occurs.

We practice all the time. (John Lennon said, speaking of their early years playing clubs, “We played so regularly we never needed to practice, we were practicing on stage.”)

Writing is one of those endeavors that we seem to require inspiration to do it. The thing is, when we teach our subconscious that it can have its own time and space in which to do this, eventually it will sync up, and when our Writing Time rolls around, our muse shows up. This is also a result of practice. We train our imagination and our subconscious to cooperate with our discipline.

Not always. We have wordless days. But over time, with diligence, those days become the exception.

One last thing before I conclude. Don’t believe that everything you write, even when you reach the point of reliably putting words down every day, is supposed to be epic. Editing is the other part of this process and that is a different process and a different set of expectations. And sometimes you throw out even good sentences, because they will not serve. The surest way to block yourself is to have unreasonable expectations. If you think after that million or two million words you should be producing Great Work every time you sit down to write, you will cripple yourself.

Just write.

Practice.

I promised to do something about our L.A. trip in September.

Over the last decade or so I realized that, unexpectedly, Harlan Ellison had become a friend. One of those with whom, despite only occasional contact, you connect with on some level which eludes description. I’ve puzzled over this from time to time, but was told by people I trust finally to just go with it.

Harlan trusted me enough to come to St. Louis for a local convention and put in an appearance despite considerable obstacles. He had suffered a stroke which left him physically diminished, he had undergone a number of blows healthwise, and, frankly, he had run himself at the edge of endurance for all his life.

I’ve written elsewhere about Harlan’s influences, on me and others, and what I thought of him as a writer. To encapsulate, I think he was remarkable and unclassifiable. He loved tilting at windmills. He tried to use his stories to expand the reader’s awareness, mostly of our own limitations, and give us an experience that might alter our perspective, emotionally, ethically, politically, and personally. To grapple with an Ellison story in its best example was to, whether we knew it or not, grapple with our own inner landscapes. In my opinion, Harlan Ellison was Up There, along with the Borges and the Vidals and the Capotes, the Lessings and the MacLeans and the Le Guins and the Munros. He managed to impact science fiction so significantly that it is difficult to talk about it without a nod to the seminal Dangerous Visions anthologies.

He did not live curtained behind his literary output. He was as voluble and controversial in his public self as he was dynamic and influential in his work and this, naturally, has led to, at best, a mixed legacy. I defy anyone to be so personally consistent and engaged at that level and make no enemies, leave behind undisturbed waters, and stir no antipathy even among those sympathetic.

Be that as it may, my acquaintance with him was surprising, enlightening, and altogether positive. He credited me with being a good writer and that is something, because he did not bullshit about that.

After his visit to St. Louis, I spoke to him a couple of times. He suggested we needed to come out there, to see him, to see the Lost Aztec Temple of Mars, to talk privately. Once more. He made me wish I’d met him ten years before I had.

For a variety of reasons, we delayed. Then I saw that the 2019 Nebula Awards were to be held in Los Angeles, so I asked Donna, what would you say to that and while we’re there we can go see Harlan and Sue? Of course, yes, call him.

I didn’t. I wanted to get a couple of things settled, line up a few more ducks, so to speak. I was going to call. I was going to call that weekend.

And at work I saw the notice of his passing.

To say that 2018 was a cruel year is too imprecise. A lot of people, friends and casual acquaintances, people we knew, were fond of, had good memories of, died last year. Harlan’s passing stung in a different way than Ursula’s, which was distinct from Vic’s. But it did sting, not least because of that intended phone call and the possible visit.

When we were called to be invited to the private memorial, there was no question of not going. We arrived on Friday, checked into our hotel, and then reached out to see what was happening. “Some of us are getting together with Sue at Mel’s Diner.” We called a cab and, because it was Friday and that time of day, we inched our way over the hill to Ventura Boulevard to join Sue and close friends.

Yes, that Mel’s Diner.

Here we are:

We were just sent this picture, which Donna shot with Marty’s phone. Marty is the one sitting opposite me. We’re the only ones with hats.

It’s a moment. I don’t know everyone in the picture. Next to Marty is Jon Manzo and next to him is Sue. The huddle to the right in the corner are more friends, in particular Tim and Andrea. Greg Ketter from Dreamhaven Books is further down on the right side of the table.

We met a lot more people the next evening at the memorial. George Takei and Walter Koenig were there, Melinda Snodgrass, George R.R. Martin, Tim and Serena Powers, L. Q. Jones, David Gerrold. A lot of stories were passed around, a lot of memories. They, however, are private.

There is a whole massive piece of my personal history entangled with Harlan Ellison from before I had any possibility of calling him on the phone. It is, for some of us, awkward to make that transition from One Who Is Influenced By to a friend. I doubtless made a bit of a fool of myself tripping over my tongue. It took a while to get over the hero worship. He made it easier than it might have been, because he had no patience with it.

You can sometimes gauge the size of someone’s soul by seeing those who will remember him fondly. Harlan’s soul was pretty damn big. And by “soul” I do not mean some ethereal afterlife wisp of religiously defined phlogiston. No, I mean the very real imprint left behind on the people who knew him, either through the work or personally.

He was here and for a while he mattered. For many of us, he still matters. And for the rest, pick up one of his books and read—he’s still here.