It was a tradition in our family for many years that at Christmastime we get together, eat, drink, make jokes, and endure the Yule Season with a skeptical resolve to give unto Santa what is Santa’s. We appreciate the spirit but the actual mechanism leaves us a bit chilly. In rejecting the corporate gloss of Xmas, though, we’ve sort of recovered some of what the holiday is supposed to mean, at least according to all the armchair philosophes.

My mother is more enamored of the childlike aspects of Christmas than my father ever was, and he indulged her. She still holds to that in her small way, even as circumstances have changed. We still try to get together around this time, though it has long been a loose calendrical event.

However, one ritual had worn on me for a long time. I write about it now because the entire country seems in the grip of ethical and moral contests which echo this seemingly minor one and it may be that exploring the small might illuminate the large in some useful way.

My father, who should be a charter member of the great Curmudgeon’s Club, picks bones as a hobby. He’s good at it. He can find something to carp about with almost any topic. He can be fun to listen to and more often than not we find ourselves nodding with sympathy at some sage formulation from his mouth.

Except this one. He thinks Ebeneezer Scrooge is a maligned and misunderstood character.

Classic conservative business-speak: “What the hell, he’s employing Cratchit! And Cratchit has a house! A house! How poor can he be if he has a house? As for Tiny Tim, what could Scrooge actually do to save his life? The kid’s a cripple, they didn’t have the medical technology back then. Would just paying Cratchit more help save his life? Everybody beats up on Scrooge and in all honesty, just what can he do?”

It was an aggravating rant because the rest of us knew there’s something he fundamentally missed, yet, like many arguments from specific points, it’s difficult to counter. My mother attempted to explain that the story isn’t about what Scrooge can do for others but what he needs to do for himself. He’s got a lot of money but he’s poor in spirit, and I imagine most people see it that way.

But I grew impatient with it after years and did a little digging.

Dickens wrote four Christmas tales, A Christmas Carol being the most famous. Each was intended to be edifying about some aspect of the Christmas Spirit and they were hugely popular in their day, and A Christmas Carol has remained so, through many reprintings and several dramatic adaptations. If all one is familiar with are the movies and television versions, it might be understood that certain aspects of the story are misapprehended, but I always found this particular view stubbornly obtuse.

Firstly, you must credit Charles Dickens for his powers of observation. Read any of his other novels and you find a severe critic who was engaged in the close inspection of the world around him. He put down in detail the ills and failures of the society in which he lived and when considering a work such as Oliver Twist or Bleak House one would be hard pressed to complain that he had gotten anything wrong. His chief power as a writer in 19th Century England was as a social critic. So, given that he was not one to complain about something just to complain and was unlikely to abandon truth and fact just to make a point (since his points were all pointedly about truth and fact), why gainsay him in this tale?

Oh, well, we have ghosts and flights of supernatural fancy! Obviously he didn’t mean it to be read at face value in those passages concerning the “real” world.

Nonsense. Credit him with keen observational skills.

Scrooge paid Cratchit 15 shillings a week. “Fifteen bob” as it says in the book. It’s difficult to be precise, but rough equivalencies can be found. The story takes place in 1841 (or thereabouts). Fifteen shillings then would be the equivalent of approximately 56£ today, or about $90.00.

Now, it is unlikely Cratchit owned that house. He likely rented it. A great deal of housing in London at the time was owned by people who may have kept a townhouse but more than likely lived elsewhere. Rental fees ranged between 2£ annually to over 300£. Dickens doesn’t discuss that, but just the cost of food, clothing, and heat especially, which was from coal, and not cheap, would have eaten up most of Cratchit’s weekly salary. Anyway one looks at it, taking care of a family of eight on less than $90.00 a week would be a challenge.

The goose was likely from a club in which funds would be pooled, paid in advance and over time, so geese could be purchased in bulk (reducing the price somewhat) and then made available to the subscribers at Christmastime. Cratchit was hardly buying such things on a weekly or even monthly basis.

As to what Scrooge might have done for Tiny Tim, well, that is difficult to say. Medicine was not advanced, causes of diseases were only vaguely understood, and many ills befell people simply from living in squalid conditions. The onset of the industrial revolution had drawn people into the cities from the farms by the thousands and they ended up shoved into tenements where the normal barriers that kept disease proliferation in check broke down. Poor hygiene, close quarters, bad water.

Patent medicines were big business. Some of them actually had palliative effects, like Turlington’s Balsam of Life, which sold for between 2 and 5 shillings a bottle (about 12 oz.). That would have been between 8% and 33% of Cratchit’s salary to treat Tiny Tim on a regular basis.

But treat him for what?

There wasn’t much accurate diagnosis of disease in 1841, but Dickens assumes in the story that Tiny Tim’s condition can be alleviated by Scrooge “loosening up” his wallet. Certain diseases Tiny Tim might have had, granted, there would have been no cure. The best that might have been done might have been to make him comfortable. But if we allow for Dickens’ accurate powers of observation, then this wasn’t one of the guaranteed fatal ones.

Tiny Tim might have had rickets. They were rampant in London at that time. The coal used to heat homes, run factories, drive boats up the Thames had filled the air with a dense soot that effectively cut down on sunshine, which would have cut down on vitamin D manufacture, and, subsequently, rickets. A better diet would help—better diet from maybe a raise by Scrooge. But rickets, even untreated, was rarely fatal.

There is a disease that fits the description. Renal Tubular Acidosis. It’s a failure of the kidneys to properly process urine and acid builds up in the blood stream. Enough of it, and it begins to attack the bones. Untreated in children, it is often fatal.

But the treatment was available at the time as a patent medicine, mainly an alkali solution like sodium bicarbonate.

Scrooge’s penny-pinching didn’t just hurt himself and his miserliness could cost Tiny Tim his life.

But it’s also true that Dickens was talking about a wider problem. The tight-fistedness of society was costing England—indeed the world—in spiritual capital. Interestingly, Dickens never, in any of his novels, suggested legislative or government intervention in poverty. He always extolled wealthy individuals to give. He thought the problem could be solved by people being true to a generous nature. It’s interesting in a man so perceptive that he recognized a problem as systemic but then suggested no systemic remedies.

In any event, on the basis of the information at hand and a couple of shrewd guesses, we can see that Dickens was not just telling us a ghost story. The consequences for Scrooge and company were quite real.

There is at the center of the Christmas Spirit, so I have been told and taught from childhood, a benefit to abandoning questions of profit and cost. That generosity should be its own reward. That mutual care is balm to the pains of society as a whole. Scrooge is a Type, one that is with us magnified in ways perhaps Dickens could not have imagined possible, a constricted soul who sees everything in terms of costs, returns on investment, labor, and balance-sheets. Everything. The point of Dickens’ story is that such people not only poison their own spiritual pond but can spread that harm to others simply by never seeing things any other way. The stubborn money-soaked impoverishment in which Scrooge lives does no one any good and the point of Christmas is to at one time a year stopping living that way.

But Dickens was not all of the spirit. He was a materialist and for him the costs were very real, in terms of hunger and disease and crippling disorder and agonizing despair, and that a man like Scrooge has real, destructive impact on the people around him, whether he knows them or not. The potential for him to Make A Difference was not some sentimental concept bound up in airy essences of fellow-feeling, but in the actual material well-being of people and, by extension, society.

I must here explain that my dad, curmudgeonly as he was in such debates, was in no way a selfish or stingy man. His response to need—need that he saw, that was tangible to him—was axiomatic and without strings. He never was a Scrooge.*

But I think it behooves us to stop paying lip service to the very old and too-oft repeated idea that “there’s nothing to be done.” We may not as individuals be able to fix everything, but we can fix something. We start by fixing ourselves.

The last word here I leave to Tiny Tim

______________

*To be clear, my dad is still alive, but circumstances have changed somewhat, and certain traditions have had to be modified to suit.

Added to the present: dad passed away in May of 2023. He is, curmudgeonliness and everything, much missed.

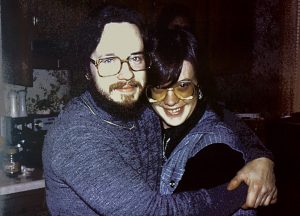

Of all the things she has done for me, the one that mattered most was that she simply accepted me. For who I was (whatever that may have been at any given moment) and supported me in anything I wanted to do. When she discovered that I wrote, she read what I had done and encouraged me to pursue it. That led, of course, to everything since. I wonder sometimes had we known how difficult it would have been, would we have done it. The writing, that is.

Of all the things she has done for me, the one that mattered most was that she simply accepted me. For who I was (whatever that may have been at any given moment) and supported me in anything I wanted to do. When she discovered that I wrote, she read what I had done and encouraged me to pursue it. That led, of course, to everything since. I wonder sometimes had we known how difficult it would have been, would we have done it. The writing, that is. I did how important she was.) Then we found an apartment on Grand Avenue, where we solidified, partied, laughed, made plans. It was from that apartment that I went to Clarion in 1988. Six weeks away, the longest we’ve ever been apart.

I did how important she was.) Then we found an apartment on Grand Avenue, where we solidified, partied, laughed, made plans. It was from that apartment that I went to Clarion in 1988. Six weeks away, the longest we’ve ever been apart. my motivations to make her proud of me, to make her feel safe with me, to make her laugh, to help her. We are very different when it comes to talents and proclivities. (It is best we clean house and so forth apart from each other.)

my motivations to make her proud of me, to make her feel safe with me, to make her laugh, to help her. We are very different when it comes to talents and proclivities. (It is best we clean house and so forth apart from each other.) many places to visit together. (We started going to science fiction conventions in 1982. We even tried out costuming a short—very short—while.)

many places to visit together. (We started going to science fiction conventions in 1982. We even tried out costuming a short—very short—while.)