This past weekend I attended our local convention, Archon. It’s a St. Louis convention that’s not actually in St. Louis, for many reasons too convoluted to go into here, and this one was number 36. Which means, with a couple of exceptions, I’ve been going to it for three decades. (Our first con was Archon 6, which featured Stephen King as GoH, and thus was something of a media circus. I met several writers, some whose work I knew and loved, others of whom I just then became acquainted—George R.R. Martin, Robin Bailey, Charles Grant, Joe Haldeman, Warren Norwood. Some have passed away, others are still working.)

I go now to meet up with friends of long acquaintance, in whose company we have spent relatively little actual face-time, but who by now have become touchstones in our lives. It’s odd having people who feel so close that you see at most one weekend a year. Granted, the internet has helped bridge those gaps, but it’s still a curious phenomenon, one which I kind of dealt with this weekend on at least one panel.

This year, the novel that seems to have garnered the most awards was Jo Walton’s Among Others. It won both the Nebula Award and the Hugo Award, both times beating out what I considered the best science fiction novel of perhaps the last decade, China Miéville’s Embassytown. Â

Now, please don’t misunderstand—I thought Among Others was a marvelous novel. I enjoyed it thoroughly, was, in fact, delighted by it, and certainly being delighted is one of the chief pleasures of reading. I do not here intend any slight on the work.

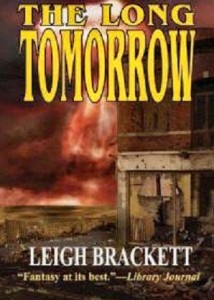

But it took two awards that are supposed to honor the best science fiction of the year, and Among Others was barely fantasy. (One of the things I admired about it was the line Walton danced around separating the fantasy from actual occurrence and simple perception on the part of the characters.) It is in the long tradition of English boarding school stories, written as the diary of a girl who is somewhat isolated, who has run away from her mad mother (who may be a witch) after a tragic loss of her sister and a crippling accident. Living with her father now, she is placed in a boarding school where her love of science fiction is one of her chief methods of coping. The novel then chronicles the succession of books she reads over a year or two, many of which were exactly the books I was reading then and loving. It is in that sense an overview of a particular period in SF, one I found myself reliving with immense pleasure.

Embassytown, on the other hand, is solidly SF built on a very meaty idea that plays out with intensity and provokes a great deal of thought—everything SF is supposed to do. It is also marvelously well-written and to my mind was hands down the best of the year, if not, as I said, the last decade.

But it lost to the Walton.

Why?

So I proposed a panel at Archon to discuss the power of nostalgia in a field that is presumed to deal with cutting edge, next level, philosophically stimulating ideas. It’s supposed to take us new places. Granted, most of it no longer does—instead it takes us to some very familiar places (after eight decades of definably “modern” SF, how many “new” places are there really to go?) and in the last couple of decades, it’s been taking us to some very old places, alá Steampunk and alternate history. I’d never given much thought to this before as a nostalgic longing because in both cases the writers are still proposing What If? scenarios that ask questions about the nature of historical inevitability and technological destiny. The story might well be set in 1890, but it’s not “our” 1890 and we have to come to grips with the questions of why “our” 1890 has preference in the nature of human development.

But Among Others didn’t even do that. It was just a recapitulation of one fan’s love of a certain era of fiction.

Again, absolutely nothing wrong with that and I say again, Among Others is a fine novel, I unhesitatingly recommend it.

My question in the panel had to do with the potential for exhaustion in SF. Paul Kincaid talks about this here in an examination of two of the best Best of the Year anthologies, Dozois’ and Horton’s. In my own reading, I’ve noticed a resurgence of old models—planetary romance, space opera, etc (Leviathan Wakes by James S.A. Corey for instance)—where we’re seeing writers take these comfortable, familiar forms and rework them with more contemporary sensibilities, broader perspectives, certainly in many instances more skillful prose. But the “cutting edge” seems to be occupying narrower slices of the collective SF zeitgeist. (William Gibson, to my mind still one of the most interesting SF writers, has all but given up writing SF in any concrete fashion and is now doing contemporary thrillers from an SF perspective. Is this cutting edge or an admission that there simply isn’t anywhere “new” to go? Likewise with Neal Stephenson, who opted to go all the way back to the Enlightenment and rework that as SF—taking the notions of epistemology and social science and applying them to the way a period we thought we knew unfolded from a shifted perspective.)

Kincaid’s piece talks about insularity in the field, which is not a new criticism—arguably, the recent upsurge in YA in the field is a direct response to the ingrown, jargon-laden incestuousness of the field in the 80s and 90s, where it seemed that if you hadn’t been reading SF since the early Seventies you simply would not understand what was going on—but I’m wondering if a new element has been added, that of an aging collective consciousness that unwittingly longs for the supposedly fertile fields of a previous Golden Age in publishing, an age before Star Trek and Star Wars and cyberpunk, when it was easier (supposedly) to write an almost pastoral kind of science fiction and you didn’t need a degree in physics or history or cultural anthropology to find your way. (I suspect the tenacity of iconic worlds like the aforementioned Star Trek and Star Wars can be explained by a very common need for continuity and familiarity with a story that you can access as much through its fashions as its ideas.)

Having just turned 58, and feeling sometimes more behind the curve both technologically and culturally, I’m wondering if, in a small way, the accolades given to a work of almost pure nostalgia is indicative of a wish for the whole magilla to just slow down.

(The trajectory of my own work over the last 20 years is suggestive, where I can see my interests shift from cool ideas, new tech, stranger settings, into more personal fiction where the internal landscapes of my characters take more and more precedence. And many of them are feeling a bit lost and clueless in the milieus in which I set them. Not to mention that I have moved from space opera to alternative history, to more or less straight history and into contemporary…)

The panel was lively and inconclusive—as I expected, because I didn’t intend answering my own question, only sparking discussion and perhaps a degree of reflection.

SF goes through cycles, like any other art form, and we see the various subsets rise and fall in popularity. There’s so much these days that I may be missing things and getting it all wrong. The reason I brought it up this time is a response to the very public recognition of a given form that, this year, seems to have trumped what I always thought science fiction is about.

I confess, there are many days I look back to when I first discovered SF, and the impact it had on my adolescent mind (and the curious fact that when I go reread some of those books I cannot for the life of me see what it was about them that did that—no doubt I was doing most of it for myself, taking cues from the works) and when I first thought about becoming a writer. It does (falsely) seem like it would have been easier “back then” to make something in the field. Such contemplation is a trap—you can get stuck in a retrograde What If every bit as powerful as the progressive What If that is supposed to be at the core of science fiction.