Category: Science Fiction

Peak Experiences

- Posted on

- – 10 Comments on Peak Experiences

This past weekend was Archon 39. Our local science fiction convention.

Donna and I have, with a couple of exceptions over the years, gone to just about all of them since number 6, which was in 1982 at the Chase-Park Plaza hotel. The guest of honor then was Stephen King, which meant that everything was exaggerated and gave us a seriously distorted set of expectations of what this convention was normally. The guest list that year was a who’s who of authors, who were then the rock stars of the convention scene. We met Joe Haldeman, Robert Bloch, Robin Bailey, George R.R. Martin, and several others. We were, you might say, agog. It was a bit overwhelming and in retrospect it was a peak experience, at least as far as conventions go.

The problem with such things is, you never know that’s what they are until some time afterward, and even then there might be some question as to how peak it was. So you go into them a bit unprepared to really appreciate them.

Not so this Archon just past. We knew months in advance that this was going to be a peak experience. Because Harlan Ellison surprised everyone by agreeing to appear, despite ill health and considerable impairment from a stroke a year ago. I knew about this immediately because I instigated the whole thing and ended up promising to be his gofer for the weekend.

As it turned out, I didn’t have to do that, Harlan has minions, and they came. But I didn’t know that until they actually arrived, so the month or so leading up to this I found myself getting more and more stressed by the responsibility I felt.

Note I say “felt” rather than “had.” What my actual responsibilities were compared to what I felt them to be were somewhat mismatched. I found myself at one point asking myself “What the hell is it with you? Calm down!” Did no good. But everything came off fairly well. Not everything that was intended to happen, did, or at least not in the way planned, but I’d say a good 70% of it worked, and the stress served one positive function other than making me obsessive about details. I knew this would be a peak experience.

Harlan is in a wheelchair. He’s partially paralyzed on his right side. There was some question as to whether or not he ought to have done this, but he would not be denied. If sheer willpower counts for anything, Harlan has enough to do pretty much what he sets his mind to doing, even in his present condition. Donna and I picked him and Susan up at the airport Thursday night around nine o’clock and took them to the hotel in Collinsville. We sat in the lobby together for a while. Two of his best friends showed up, Tim and Andrea Richmond, who we now count as friends.

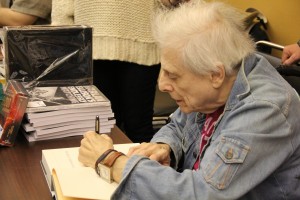

By Friday evening’s opening ceremonies, Harlan’s presence at the con was unmistakable.  I wheeled him up on stage after he had spent over an hour signing books. He’s slower, sure, but the mind is as alert and sharp as ever. He was pleased to be at the convention and he disarmed everyone.

I wheeled him up on stage after he had spent over an hour signing books. He’s slower, sure, but the mind is as alert and sharp as ever. He was pleased to be at the convention and he disarmed everyone.

We who have been involved in SF for any length of time know The Stories. Harlan can pop off at the drop of a moronic comment and hides have been flayed (metaphorically) and sensibilities challenged. If I heard it once I heard it fifty time, “He’s so gracious!” Yes, he is. He has a heart of enormous proportions.

He was physically unable to do as much as he clearly wanted to, but under the circumstances what he did do was generous and impressive.

Peak Experience time. I got to be on a panel with Harlan Ellison.

Let me explain. I grew up reading stories by the giants of the field when most of them were still alive and many still publishing. For me, the pantheon includes Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, Alfred Bester, Robert Heinlein, C.L.Moore, Alice Sheldon, Joanna Russ, C.J. Cherryh…well, you get the idea. And Harlan, who wrote like a fey combination of Bradbury and Bester with a touch of Borges stirred in and made everyone react viscerally in ways they did not react to their other favorites. I recall getting very turned off by Harlan when I was, say 15, and then later coming back and trying his work again only to find that I had missed almost everything important about the stories the first go-round. He was like a tornado whirling through the more deliberative winds of his peers. I’m still not sure I “get” everything that is going on in an Ellison story, but that’s the sign of a work worthy of ongoing consideration.

Of the aforementioned bunch, I shook Asimov’s hand, chatted with Bradbury and Cherryh, never met Bester, Heinlein, Moore, Russ, or Sheldon. There are a couple of dozen other Greats I’ve had opportunity exchanged words with. I’ve been on panels with Gene Wolfe, Frederik Pohl, Elizabeth Ann Hull, a number of others. So many are just gone.

I got to be on a panel with Harlan. The 12-year-old in me was having a field day. This, I thought, is as good as it gets. At least in my list of cool things to do.

After 2010, I never thought I’d see Harlan again. Certainly not at a convention. He’d said he was done with them.  Who could blame him? He’s tired. We talk on the phone occasionally. I like him, but most of the time I don’t quite know what to say to him, other than some variation of Thank You For Being a Powerful Aesthetic Presence In My Life. Of all the acquaintances I thought I might make in this curious life and profession, his was unexpected.

Who could blame him? He’s tired. We talk on the phone occasionally. I like him, but most of the time I don’t quite know what to say to him, other than some variation of Thank You For Being a Powerful Aesthetic Presence In My Life. Of all the acquaintances I thought I might make in this curious life and profession, his was unexpected.

So when this opportunity came up, by a series of unexpected steps, I was torn. Certainly his health is problematic and he’s 81. This probably was not, for a number of reasons, a good idea. On the other hand, when I reach that point in my life and there’s something I want to do and believe I can do it, I hope there are people who will help me do it. I do rather doubt I’ll see him again. I don’t know when we’ll be able to get to L.A. anytime remotely soon. But I did get to spend a good chunk of this weekend with him and it was surprising and rich and bittersweet.

He charmed practically the whole convention, signed a boatload of books, gave of himself until he just couldn’t. I’m sure he got as good as he gave. I will confess that I was waiting for someone, anyone, to start anything negative with him. It would not, had I been there, lasted long. But no one did, everyone seemed so gobsmacked pleased to see him.

We did not take him back to the airport on Sunday. Other, closer friends did that. He recorded a thankyou and goodbye for closing ceremonies, which was classic Ellison.

I confess, it’s strange. Coming from a place in life never expecting to ever say a single sentence to him, he has become one of the major influences and associations in my life. All told, I doubt we’ve spent a week’s time together. But it’s always been memorable. I’m about to wander into mawkishness now, so I’ll wrap it up with two final images and maybe one more line.

So there we have it.

Peak Experience.

I hope he hangs around for many more years, as long as his mind is clear and his imagination active and he feels welcome. There are a lot of people—a LOT—who are very glad of his presence.

I know I’m glad to know him.

Updates

- Posted on

- – 1 Comment on Updates

This coming weekend is Archon 39, our local SF convention. For the last two months I’ve been rushing about, often only in my own head, to prepare. This year is special in a number of ways. Harlan Ellison is attending. Now, unless one keeps abreast of such things, that alone is no explanation for the level of anxiety I’ve been feeling about this. For one, I instigated this event, largely without intending to. For another, I’ve been involved in arranging things for him and his wife, Susan. I’ve consequently been more involved in Archon than in previous years. But today, Monday, I can honestly say I have covered as many bases as it is possible. The unforeseen is…e=unforeseeable.

That’s not the only thing going. Those of you who have been following me on Twitter will know that I have been updating my computers. That has been both less bothersome and more annoying than it ought to be, but is now largely done. (I have one more thing to get, but it will keep till later.) I’m now well into the 21st Century on that front and not a moment too soon. This morning I took care of the last bit of bother for Archon that is in my power to take care of, so I spent the last twenty minutes playing with the theme on my blog. I think I’m sticking with this one for a time. How do you like it? I feel it is a theme of great nift.

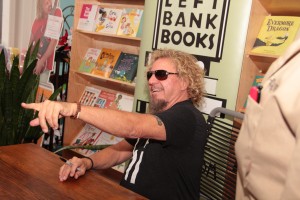

Recently, Left Bank Books hosted an event with Sammy Hagar. He has a new cookbook out (yes, that Sammy Hagar, and, yes, I said a cookbook) and we ushered through a myriad of his ecstatic fans and sold a ton of them. So for no other reason than I have it on hand, here’s a photo of Mr. Hagar.

We have all more or less recovered from the chaos and excitement of that day, which was one day in a week filled with notable events. Jonathan Franzen was also in town and we (not I) worked that event. And earlier we hosted Mr. Jeff Smith, former Missouri state senator who went to prison and has, since release, dedicated himself to prison reform. He has a new book out about it. I did work that event and must report that some of what he said, while not surprising, was nevertheless disturbing. The whole fiction of “rehabilitation” in regards to incarceration…

Well, I may have more to say on that later.

I’m unwinding as I write this, so forgive me if I wander about from topic to topic. Last night we had friends over to dinner and it was terrific. Good food, great conversation, laughing…we don’t do nearly enough of that. Partly it’s the time thing, but you know, you can lose the habit of being social, and over the last several years we’ve seen our skills erode. We may be coming out of a long hibernation, but then there is still the time thing, and I have a book to write over the next several months. (Hence the new computers.)

On that front, this Saturday past I was one of eight local authors invited to attend the Carondolet Authors’ Brunch. Strange thing that it was, it was nevertheless fun. They arranged tables and set it up like speed dating. The authors would visit each table for 15 minutes, then move to the next, and so on. I was delighted that no two tables produced the same conversation, although some variation of “where do you get your ideas” came up each time, but that was only one of two questions that I found repeated. The other was “Do you teach?”

There were a couple of household repairs I tended to this morning and now I’m procrastinating here. I should be writing something serious, profound, or at least with the potential to earn income, but I’m fooling around with my blog theme and gossiping.

…And I just realized I have one more thing to take care of for Archon.

That said, this Thursday we’re trying something at Left Bank Books that I hope will establish a tradition. We’re having three of the major guests in the store for a kind of pre-con event. Jacqueline Carey, of Kushiel’s Dart fame; Esther Friesner, of multiple fames; and Vic Milan, who has been the toastmaster at Archon’s masquerade since forever, and if you like costuming and haven’t been to an Archon masquerade, you’re missing a real treat, of which Vic is a major part. So, seven o’clock Thursday night, October 1st, be there or be a tessaract.

After Archon I intend to find a corner and melt down into it.

Until then, thanks for stopping by.

Bragging

My collection, Gravity Box and Other Spaces, has received some attention since it came out last year. (Last year? Really? Yeesh!)

Two critics in particular have been kind to it. The first, from the estimable Rich Horton, who does one of the Best of the Year anthologies (and I urge you all to check it out), wrote the following in LOCUS last December:

“Mark W. Tiedemann is the author of a fine space opera trilogy, The Secantis Sequence, that deserves a wider audience, as well as of strong stories in places like SF Age and F&SF. He hasn’t been entirely silent the past several years, but he hasn’t been as much in evidence as I’d like, so it’s nice to see a new collection, Gravity Box and Other Spaces, appear featuring a few reprints (including his outstanding early story “The Playground Door”) and a number of original stories. My favorites include one fantasy and one SF story. “Preservation” is about a gamekeeper in service to a King who commands him to poach the horn of an einhyrn, reputed to determine if a woman is a virgin. The King wants to make sure his son’s intended bride is pure, but it’s soon clear that dirtier politics than that are involved – not to mention that the einhyrn are a protected species. Solid adventure, and involving characters. I liked “Forever and a Day” even more, a time dilation story about a woman in a polyamorous marriage, who turns out to be unable to tolerate new treatments conferring immortality. Her husband and wife become immortal, while she joins the crew of a starship, gaining a sort of immortality due to time dilation. A cute idea in itself, though hardly new, but the story asks effectively how any relationship can survive centuries – indeed, how one’s relationship with one’s own self can survive centuries, and whether immortality is better than the sort of continual revivification star travel might bring.”

And now this from Paul di Filippo, in the July Asimov’s:

“The title and cover image of Mark Tiedemann’s Gravity Box and Other Spaces…might lead you to believe that its table of contents hold nothing but hard SF. But instead we find a panoply of genres. The book opens strongly with a Stephen King-style contemporary bit of weirdness titled “Miller’s Wife.” A futuristic story involving robot nursemaids/surrogates of a sort, “Redaction” evokes feelings similar to viewing Spielberg’s A.I. “The Disinterred” is a strong blend of steampunk, specters, and religion, as a man goes searching for his lost wife and runs into a scientific expedition instead. And the title piece tracks the fortunes of a teenage girl who must rebel against the ignorance of her family and the laws of society to attain a future in space. Tiedemann’s range is large, his heart big, and his skills and insights deserving of your attentions.” Paul Di Filippo, July 2015 Asimov’s SF.

I’m blushing. No I’m not. Well, maybe a little. I am very grateful. For the record, these are the first reviews of one of my books I ever received from either of these publications. Just goes to show, it’s never too late to have a good start to one’s career.

Interview

I did an interview yesterday. Here’s the You Tube of it. It’s not as smooth as I’d like but it’s the result the fact that I’m in the Bronze Age, technologically. I had a difficult time hearing Sally Ember here, though that may not be readily apparent from this. I really need to upgrade all my systems. It would be nice if life would stop throwing me curve balls that keep costing me money I’d prefer to spend on new computers. However, I offer it here as one my few video bits. I recommend checking about Sally’s site, she has a lot of interviews there. CHANGES.

Spoiling the Punch

- Posted on

- – 1 Comment on Spoiling the Punch

This is almost too painful. The volume of wordage created over this Sad Puppies* thing is heading toward the Tolstoyan. Reasonableness will not avail. It’s past that simply because reasonableness is not suited to what has amounted to a schoolyard snit, instigated by a group feeling it’s “their turn” at dodge ball and annoyed that no one will pass them the ball.

Questions of “who owns the Hugo?” are largely beside the point, because until this it was never part of the gestalt of the Hugo. It was a silly, technical question that had little to do with the aura around the award. (As a question of legalism, the Hugo is “owned” by the World Science Fiction Society, which runs the world SF conventions. But that’s not what the question intends to mean.)

Previously, I’ve noted that any such contest that purports to select The Best of anything is automatically suspect because so much of it involves personal taste. Even more, in this instance, involves print run and sales. One more layer has to do with those willing to put down coin to support or attend a given worldcon. So many factors having nothing to do with a specific work are at play that we end up with a Brownian flux of often competing factors which pretty much make the charge that any given group has the power to predetermine winners absurd.

That is, until now.

Proving that anything not already overly organized can be gamed, one group has managed to create the very thing they have been claiming already existed. The outrage now being expressed at the results might seem to echo back their own anger at their claimed exclusion, but in this case the evidence is strong that some kind of fix has been made. Six slots taken by one author published by one house, with a few other slots from that same house, a house owned by someone who has been very vocal about his intentions to do just this? Ample proof that such a thing can be done, but evidence that it had been done before? No, not really.

Here’s where we all find ourselves in unpleasant waters. If the past charges are to be believed, then the evidence offered was in the stories and novels nominated. That has been the repeated claim, that “certain” kinds of work are blocked while certain “other” kinds of work get preferential treatment, on ideological grounds. What grounds? Why, the liberal/left/socialist agenda opposed to conservatism, with works of a conservative bent by outspoken or clearly conservative authors banished from consideration in favor of work with a social justice flavor. Obviously this is an exclusion based solely on ideology and has nothing to do with the quality of the work in question. In order to refute this, now, one finds oneself in the uncomfortable position of having to pass judgment on quality and name names.

Yes, this more or less is the result of any awards competition anyway. The winners are presumed to possess more quality than the others. But in the context of a contest, no one has to come out and state the reason “X” by so-and-so didn’t win (because it, perhaps, lacked the quality being rewarded). We can—rightly—presume others to be more or less as good, the actual winners rising above as a consequence of individual taste, and we can presume many more occupy positions on a spectrum. We don’t have to single anyone out for denigration because the contest isn’t about The Worst but The Best.

But claiming The Best has been so named based on other criteria than quality (and popularity) demands comparisons and then it gets personal in a different, unfortunate, way.

This is what critics are supposed to do—not fans.

In order to back their claims of exclusion, exactly this was offered—certain stories were held up as examples of “what’s wrong with SF” and ridiculed. Names were named, work was denigrated. “If this is the kind of work that’s winning Hugos, then obviously the awards are fixed.” As if such works could not possibly be held in esteem for any other reason than that they meet some ideological litmus test.

Which means, one could infer, that works meeting a different ideological litmus test are being ignored because of ideology. It couldn’t possibly be due to any other factor.

And here’s where the ugly comes in, because in order to demonstrate that other factors have kept certain works from consideration you have to start examining those works by criteria which, done thoroughly, can only be hurtful. Unnecessarily if such works have an audience and meet a demand.

For the past few years organized efforts to make this argument have churned the punchbowl, just below the surface. This year it erupted into clear action. The defense has been that all that was intended was for the pool of voters to be widened, be “more inclusive.” There is no doubt this is a good thing, but if you already know what kind of inclusiveness you want—and by extension what kind of inclusiveness you don’t want, either because you believe there is already excess representation of certain factions or because you believe that certain factions may be toxic to your goal—then your efforts will end up narrowing the channel by which new voices are brought in and possibly creating a singleminded advocacy group that will vote an ideological line. In any case, their reason for being there will be in order to prevent Them from keeping You from some self-perceived due. This is kind of an inevitability initially because the impetus for such action is to change the paradigm. Over time, this increased pool will diversify just because of the dynamics within the pool, but in these early days the goal is not to increase diversity but to effect a change in taste. What success will look like is predetermined, implicitly at least, and the nature of the campaign is aimed at that.

It’s not that quality isn’t a consideration but it is no longer explicitly the chief consideration. It can’t be, because the nature of the change is based on type not expression.

Now there is another problem, because someone has pissed in the punchbowl. It’s one of the dangers of starting down such a path to change paradigms through organized activism, that at some point someone will come along and use the channels you’ve set up for purposes other than you intended. It’s unfortunate and once it happens you have a mess nearly impossible to fix, because now no one wants to drink out of that bowl, on either side.

Well, that’s not entirely true. There will be those who belly up to the stand and dip readily into it and drink. These are people who thrive on toxicity and think as long as they get to drink from the bowl it doesn’t matter who else does or wants to. In fact, the fewer who do the better, because that means the punch is ideally suited to just them. It’s not about what’s in the bowl but the act of drinking. Perhaps they assume it’s supposed to taste that way but more likely they believe the punch has already been contaminated by a different flavor of piss, so it was never going to be “just” punch. They will fail to understand that those not drinking are refraining not because they don’t like punch but because someone pissed in the bowl.

As to the nature of the works held up as examples of what has been “wrong” with SF…

Science fiction is by its nature a progressive form. It cannot be otherwise unless its fundamental telos is denied. Which means it has always been in dialogue with the world as it is. The idea that social messaging is somehow an unnatural or unwanted element in SF is absurd on its face. This is why for decades the works extolled as the best, as the most representative of science fiction as an art form have been aggressively antagonistic toward status quo defenses and defiantly optimistic that we can do better, both scientifically and culturally. The best stories have been by definition social message stories. Not preachments, certainly, but that’s where the art comes in. Because a writer—any writer—has an artisitic obligation, a commitment to truth, and you don’t achieve that through strident or overt didacticism. That said, not liking the specific message in any story is irrelevant because SF has also been one of the most discursive and self-critical genres, constantly in dialogue with itself and with the world. We have improved the stories by writing antiphonally. You don’t like the message in a given story, write one that argues with it. Don’t try to win points by complaining that the message is somehow wrong and readers don’t realize it because they keep giving such stories awards.

Above all, though, if you don’t win any awards, be gracious about it, at least in public. Even if people agree with you that you maybe deserved one, that sympathy erodes in the bitter wind of performance whining.

______________________________________________________________________________________

*I will not go into the quite lengthy minutiae of this group, but let me post a link here to a piece by Eric Flint that covers much of this and goes into a first class analysis of the current situation. I pick Eric because he is a Baen author—a paradoxical one, to hear some people talk—and because of his involvement in the field as an editor as well as a writer.

We Prospered: Leonard Nimoy, 1931 to 2015

He was, ultimately, the heart and soul of the whole thing. The core and moral conscience of the congeries that was Star Trek. Mr. Spock was what the entire thing was about. That’s why they could never leave him alone, set him aside, get beyond him. Even when he wasn’t on screen and really could be nowhere near the given story, there was something of him. They kept trying to duplicate him—Data, Seven-of-Nine, Dax, others—but the best they could do was borrow from the character.

I Am Not Spock came out in 1975. It was an attempt to explain the differences between the character and the actor portraying him. It engendered another memoir later entitled I Am Spock which addressed some of the misconceptions created by the first. The point, really, was that the character Spock was a creation of many, but the fact is that character would not exist without the one ingredient more important than the rest—Leonard Nimoy.

I was 12 when Star Trek appeared on the air. It is very difficult now to convey to people who have subsequently only seen the show in syndication what it meant to someone like me. I was a proto-SF geek. I loved the stuff, read what I could, but not in any rigorous way, and my material was opportunistic at best. I was pretty much alone in my fascination. My parents worried over my “obsessions” with it and doubtless expected the worst. I really had no one with whom to share it. I got teased at school about it, no one else read it, even my comics of choice ran counter to the main. All there was on television were movie re-runs and sophomoric kids’ shows. Yes, I watched Lost In Space, but probably like so many others I did so out of desperation, because there wasn’t anything else on! Oh, we had The Twilight Zone and then The Outer Limits, but, in spite of the excellence of individual episodes, they just weren’t quite sufficient. Too much of it was set in the mundane world, the world you could step out your front door and see for yourself. Rarely did it Go Boldly Where No One Had Gone Before in the way that Star Trek did.

Presentation can be everything. It had little to do with the internal logic of the show or the plots or the science, even. It had to do with the serious treatment given to the idea of it. The adult treatment. Attitude. Star Trek possessed and exuded attitude consistent with the wishes of the people who watched it and became devoted to it. We rarely saw “The Federation” it was just a label for something which that attitude convinced us was real, for the duration of the show. The expanding hegemony of human colonies, the expanse of alien cultures—the rather threadbare appearance of some of the artifacts of these things on their own would have been insufficient to carry the conviction that these things were really there. It was the approach, the aesthetic tone, the underlying investment of the actors in what they were portraying that did that. No, it didn’t hurt that they boasted some of the best special effects on television at that time, but even those couldn’t have done what the life-force of the people making it managed.

And Spock was the one consistent on-going absolutely essential aspect that weekly brought the reality of all that unseen background to the fore and made it real. There’s a reason Leonard Nimoy started getting more fan mail than Shatner. Spock was the one element that carried the fictional truth of everything Star Trek was trying to do.

And Spock would have been nothing without the talent, the humanity, the skill, the insight, and the sympathy Leonard Nimoy brought to the character. It was, in the end, and more by accident than design, a perfect bit of casting and an excellent deployment of the possibilities of the symbol Spock came to represent.

Of all the characters from the original series, Spock has reappeared more than any other. There’s a good reason for that.

Spock was the character that got to represent the ideals being touted by the show. Spock was finally able to be the moral center of the entire thing simply by being simultaneously on the outside—he was not human—and deeply in the middle of it all—science officer, Starfleet officer, with his own often troublesome human aspect. But before all that, he was alien and he was treated respectfully and given the opportunity to be Other and show that this was something vital to our own humanity.

Take one thing, the IDIC. Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combination. It came up only a couple of times in the series, yet what a concept. Spock embodied the implications even in his trademark comment “Fascinating.” He was almost always at first fascinated. He wanted before anything else to understand. He never reacted out of blind terror. Sometimes he was on the other side of everyone else in defense of something no one seemed interested in understanding, only killing.

I’m going on about Spock because I know him. I didn’t know Mr. Nimoy, despite how much he gave of himself. I knew his work, which was always exemplary, and I can assume certain things about him by his continued affiliation with a character which, had he no sympathy for, would have left him behind to be portrayed by others long since. Instead, he kept reprising the role, and it was remarkably consistent. Spock was, throughout, a positive conscience.

On the side of science. I can think of no other character who so thoroughly exemplified rational morality. Spock had no gods, only ideals. He lived by no commandments, only morality. His ongoing championing of logic as the highest goal is telling. Logic was the common agon between Spock and McCoy, and sometimes between Spock and Kirk. I suspect most people made the same mistake, that logic needs must be shorn of emotion. Logic, however, is about “sound reasoning and the rules which govern it.” (Oxford Companion to Philosophy) This is one reason it is so tied to mathematics. But consider the character and then consider the philosophy. Spock is the one who seeks to understand first. Logic dictates this. Emotion is reactive and can muddy the ability to reason. Logic does not preclude emotion—obviously, since Spock has deep and committed friendships—it only sets it aside for reason to have a chance at comprehension before action. How often did Spock’s insistence on understanding prove essential to solving some problem in the show?

I suspect Leonard Nimoy himself would have been the first to argue that Spock’s devotion to logic was simply a very human ideal in the struggle to understand.

Leonard Nimoy informed the last 4 decades of the 20th Century through a science fictional representation that transcended the form. It is, I believe, a testament to his talent and intellect that the character grew, became a centerpiece for identifying the aesthetic aspects of what SF means for the culture, and by so doing became a signal element of the culture of the 21st Century.

Others can talk about his career. He worked consistently and brought the same credibility to many other roles. (I always found it interesting that one his next roles after Star Trek was on Mission: Impossible, taking the place of Martin Landau as the IM team’s master of disguise. As if to suggest that no one would pin him down into a single thing.) I watched him in many different shows, tv movies, and have caught up on some of his work prior to Star Trek (he did a Man From U.N.C.L.E. episode in which he played opposite William Shatner) and in my opinion he was a fine actor. He seems to have chosen his parts carefully, especially after he gained success and the control over his own career that came with it. But, as I say, others can talk about that. For me, it is Spock.

I feel a light has gone out of the world. Perhaps a bit hyperbolic, but…still, some people bring something into the world while they’re here that has the power to change us and make us better. Leonard Nimoy had an opportunity to do that and he did not squander it. He made a difference. We have prospered by his gifts.

I will miss him.

Getting Out Of Your Own Head

- Posted on

- – 4 Comments on Getting Out Of Your Own Head

I didn’t know Samuel R. Delany was black until I’d read damn near all his books, a project that took some time. I’m talking about a revelation that came sometime in the early 80s. Now, you might think I was a bit of an idiot for taking that long, but I had zero involvement in fandom prior to 1982 and if there were no jacket photos of authors I had not clue one concerning the first thing about them. (Mainly because I actually didn’t much care; it was the work that concerned me, not the celebrity.)

Still, you’d think that the original cover illustration for Heavenly Breakfast, with a portrait of Chip, would have clued me in. But it didn’t. Not because I assumed he was white (or, later, straight), but that I didn’t care. One of my favorite writers from the big trunk of books my mother had kept from her days in the Doubleday Book Club was Frank Yerby. One of them had an author photo on the back so I knew he was African American, but it didn’t register as noteworthy because I honestly didn’t think it was important.

Mind you, I’m not saying I had no racist attributes. Like any white boy growing up in St. Louis, I had my share of prejudices (and I’ve written about some of them here ) but I was always something of an outlier and a good deal of my prejudice had little to do with skin color and mostly to do with what I perceived as life choices. It never occurred to me blacks (or any other ethnic category) couldn’t do anything I could do if they wanted to. (I was young and stupid and the lessons of 20th Century institutional discrimination had yet to really sink in. Bear with me.) But I will confess that unless it was put before me directly I sort of defaulted to the assumption that most writers were white.

It didn’t bother me when I found out otherwise.

That was the world I lived in and while I question many assumptions I didn’t question all of them—that can get exhausting and perhaps even a little counter-productive if that exhaustion leads to a desire to stop worrying about everything.

But as I grew older, anytime I discovered a new writer I liked was other than my base assumption, I had a little frisson of delight. I never once felt threatened, it never occurred to me to feel besieged or that I was in any danger of losing something. You can do that when you belong to the dominant culture. You know, in the very fiber of your being, that these other folks pose no such threat to you and the hegemony in which you live. You can be…gracious.

Which is kind of an ugly thing when you think about it. Why should I have to be gracious just because somebody who doesn’t fit a particular profile does something other members of my culture don’t think they (a) can or (b) should? Gracious implies permission. Gracious implies special circumstances. Gracious implies accommodation, as if you have the authority to grant it. Gracious, in this context, means power. (Everyone interested in this should read Joanna Russ’s excellent How To Suppress Women’s Writing to see how the process of marginalization and delegitimizing works.)

As it turned out, I have both been reading diversely and reading based on false assumptions about merit for a long time, but it was a problem, once I realized it, caused me no pain other than momentary embarrassment. It was an opportunity to expand my reading.

Sure, it opened me to works which called certain attitudes with which I’d lived my whole life into question. But, hell, that’s one of the primary reasons I read. What’s the point of reading nothing but work that does little more than give you a pleasant massage? Those kinds of books and stories are fine (and frankly, I can get plenty of that from movies and television, I don’t have to spend valuable hours reading things that feed my biases and act as soporific), but they should only be breathers taken between books that actively engage the intellect and moral conscience. Which books tend to piss you off on some level.

Depending on how pissed off you get, this may be a good way of finding out where perhaps you need to do a little personal assessment. However, that’s up to the individual. You can just as easily choose to revel in being pissed off and take that as the lesson.

“But reading stories is supposed to be entertainment. If I want edification I’ll read philosophy.”

Two things about that. Yes, fiction is supposed to be entertaining. If it isn’t, it’s not very good fiction. But there are two meanings to the word “entertain” and while one of them is about sitting back and enjoying a ride the other is more nuanced and has to do with entertaining ideas, which is less passive and, yes, edifying. Because the second thing is, just what do you consider reading fiction if not reading philosophy? Guess what, if you read a lot of fiction, you’ve been reading philosophy, at least on a certain level. Because philosophy is, at base, an examination of how we live and what that means and all stories are about how people live and what it means to them. (This is one of the ways in which fiction and essay often rest cheek-to-cheek in terms of reading experience.) The deeper, the meatier the story, the more philosophical.

Which is why some books become cause celebrés of controversy, because everyone gets it that they’re talking about life choices. Catcher In The Rye, To Kill A Mockingbird, Huckleberry Finn… how are these novels not fundamentally philosophical?

Which is why the idea of telling the truth in fiction has real meaning. “How can a bunch of made up stuff—lies—tell the truth?” A simpleminded question that assumes fact and truth are somehow the same. Yes, they’re related, but truth is not an artifact, it is a process and has to do with recognition. (Do you sympathize with the characters? Yes? Then you have found a truth. You just have to be open to the idea. It’s not rocket science, but it is philosophy.)

The most important factor in hearing a truth is in listening. You can’t listen if you shut your ears. And you can’t learn about a previously unrecognized truth if you keep listening to the same mouths, all the time. You have to try out a different tongue in order to even expose yourself to a new truth. Furthermore, you can never find the point of commonality in those alien truths if you don’t pay attention to what they’re saying.

Commonality seems to disturb some people. Well, that’s as it should be. Commonality is disturbing. It’s mingling and mixing, it’s crossing lines, violating taboos, and reassessing what you thought you knew in order to find out how you are like them. Commonality is not one thing, it’s an alloy. More than that, it’s a process. Because as you find commonality with the foreign, the alien, the other, they’re finding commonality with you.

Which brings me to the main subject of this piece, namely the challenge put forth by K. Tempest Bradford to read something other than straight white male authors for a year. Go to the link and read the piece, then come back here.

Okay. Contrary to what the nattering blind mouths of righteous indignation have been saying, Tempest is NOT saying give up reading what you’ve always liked. She’s suggesting it would be worthwhile to try this for a year. How is this any different than someone saying “Maybe it would be a good thing to read nothing but history books for a year” or “I’m taking this year to read nothing but 19th Century novels”? Like any book club or reading group, she’s set the parameters of a challenge. Take it on or go away. Why the need to vent OWS* all over her?

I have my theories about that and others have mentioned some of them, but what I want to know here is why certain people take this as an attack on their “culture” and condemn the idea as bigoted when, at worst, it’s just push back against an unexamined set of assumptions that have prevailed all along?

What troubles me in all these reactions as well is a certain hypocrisy coming from my own group, namely science fiction writers. We have felt under siege for decades by the so-called mainstream—judged, dissed, ill-regarded, consigned to the purgatory of “genre” and not invited to all the good parties—and we have, collectively, been justifiably irked by attitudes which, we believed, would evaporate if you people would just loosen up and read some of the work you’re putting down! Look in a mirror, folks.

(A more reasonable objection to Tempest is expressed here by Laura Resnick, and she addresses part of the problem I began this essay with, namely that normally one has to go out of one’s way to find out personal information about the authors in question in order to do what she’s suggesting, and that does have the danger of displacing the merit of the work with an over-reliance on others factors. However, it’s not as if this is (a) not a problem being talked about or (b) in any way easily addressed.)

There’s also an element of rage politics in this which is stunning in its idiocy. It’s the way our current culture works, that everything can be made into a cause to be outraged. “I prefer XYZ nailclippers to any other.” “XYZ nailclippers are made in China! Preferring them shows you to be an anti-American libtard self-loathing traitor! True Americans use ABC nailclippers!”**

Really? Are we so sensitive anymore that we can’t allow for a little more room on the very wide sofa we inhabit for a difference of opinion and maybe a little challenge?

The fury over last year’s SF awards generated by a certain group over what they perceived as an assault on their definition of science fiction by the evident expansion of what is considered good SF is indicative of a kind of entrenchment I would have thought anathema to science fiction. It’s too easy to read the diatribes and think the whole SF community is in uproar over something it has been striving to overcome for lo these many decades. This is the problem of the megaphone effect.

But what Tempest and others are talking about goes well beyond the SF world. There is a problem with recognition of non-approved viewpoints and faces. The ocean of publishing is constantly a-roil, so depending on where you look it may be hard to see, and if you’re committed to seeing only what you expect then you can very easily miss it in the chop. But the question is, how does it harm anyone to consider the voices of others as relevant and entertaining as what you’re used to hearing? Why does the prospect of change so frighten people who have the intellect to know better? Why is it necessary to tag someone a bigot when they suggest that maybe the homogenization of our culture is a bad thing?

I’d like to argue that you have nothing to fear, that there isn’t anything inherently wrong with White Culture, but just writing that line brings me up to the chief problem—what White Culture? I mean, we have to assume, don’t we, that there is one thing that’s being described by that? It’s really as erroneous and useless a descriptor as Black Culture. Which one? The reality is, in both cases, they only exist as a consequence of definitional tactics that seek to reduce experience into an easily codifiable box that leaves out more diversity than it could possibly include. I am white, and in terms of writing, I can say pretty confidently that, say, Jonathan Franzen does not represent my “culture.” It’s kind of an absurd statement on the face of it. Attitudinally, I have almost nothing in common with him, or the kind of writing he represents, or the particular viewpoint he deploys.

White Culture is only relevant in terms of social power and its exercise and in that sense I can claim affiliation with it by default. I can’t not be part of it because that’s how the boundaries are set.

But I don’t have to exemplify it in my own person.

This is what reading has given me—the ability to access experiences not my own. And, by extension, understand that all experiences are not the same even as they share certain common traits. And the entire purpose and value of deep reading is to be More. More than what my context prescribes. More than what my social situation allows.

So why would I feel threatened by Tempest’s challenge? I might not stick with it, but I do not see her as claiming the work she would have me read is somehow superior to what I normally would, nor is she claiming that the white male work to which she refers is all intrinsically bad. What she is not saying is as important as what she is. She’s basically challenging us to do what we would normally do anyway, with one more filter in place to select for experiences outside our comfort zone.

On the one hand, it’s kind of “well, why not?” proposition. What could it hurt?

On the other, it’s a serious attempt at overcoming the bunker mentality that seems to be the norm these last couple decades. Retrenchment is the order of the day for some folks. Any suggestion that the walls of the bubble in which people live are perhaps insufficient for the problems of the world gets treated to bitter denouncements. It’s tiring. It’s destructive.

No, Tempest is not being a bigot. She prescribing a way—modest though it may be—of overcoming bigotry.

It’s an invitation. She’s not being gracious about it. She’s being welcoming.

___________________________________________________________________________

*OWS—Oppressed White Spleen. If “they” can lob acronyms around to make their point, so can I.

**Yes, much of it is exactly that idiotic. We find ourselves in otherwise casual interactions often forced to take do-or-die political positions over the most inane matters all in service to sorting out who’s in our group and who’s out. I am talking about extremes here, but it pervades everything. I recall a conversation once where the efficacy of ethanol was being discussed and when I brought up the actual inefficiency of it, both chemically and economically, the response I got had to do with energy independence and patriotism. There was no room for the vast world of money or lobbies or special interests or alternatives. I was either in or out. We’ve reduced much of our normal discourse to the parameters of a football game.

Nebula Awards

- Posted on

- – 2 Comments on Nebula Awards

The Nebula Awards nominees for the best SFF of 2014 have been announced.

Novel

- The Goblin Emperor, Katherine Addison (Tor)

- Trial by Fire, Charles E. Gannon (Baen)

- Ancillary Sword, Ann Leckie (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- The Three-Body Problem, Cixin Liu (), translated by Ken Liu (Tor)

- Coming Home, Jack McDevitt (Ace)

- Annihilation, Jeff VanderMeer (FSG Originals; Fourth Estate; HarperCollins Canada)

Novella

- We Are All Completely Fine, Daryl Gregory (Tachyon)

- Yesterday’s Kin, Nancy Kress (Tachyon)

- “The Regular,” Ken Liu (Upgraded)

- “The Mothers of Voorhisville,” Mary Rickert (Tor.com 4/30/14)

- Calendrical Regression, Lawrence Schoen (NobleFusion)

- “Grand Jeté (The Great Leap),” Rachel Swirsky (Subterranean Summer ’14)

Novelette

- “Sleep Walking Now and Then,” Richard Bowes (Tor.com 7/9/14)

- “The Magician and Laplace’s Demon,” Tom Crosshill (Clarkesworld 12/14)

- “A Guide to the Fruits of Hawai’i,” Alaya Dawn Johnson (F&SF 7-8/14)

- “The Husband Stitch,” Carmen Maria Machado (Granta #129)

- “We Are the Cloud,” Sam J. Miller (Lightspeed 9/14)

- “The Devil in America,” Kai Ashante Wilson (Tor.com 4/2/14)

Short Story

- “The Breath of War,” Aliette de Bodard (Beneath Ceaseless Skies 3/6/14)

- “When It Ends, He Catches Her,” Eugie Foster (Daily Science Fiction 9/26/14)

- “The Meeker and the All-Seeing Eye,” Matthew Kressel (Clarkesworld 5/14)

- “The Vaporization Enthalpy of a Peculiar Pakistani Family,” Usman T. Malik (Qualia Nous)

- “A Stretch of Highway Two Lanes Wide,” Sarah Pinsker (F&SF 3-4/14)

- “Jackalope Wives,” Ursula Vernon (Apex 1/7/14)

- “The Fisher Queen,” Alyssa Wong (F&SF 5/14)

Ray Bradbury Award for Outstanding Dramatic Presentation

- Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), Written by Alejandro G. Iñárritu, Nicolás Giacobone, Alexander Dinelaris, Jr. & Armando Bo (Fox Searchlight Pictures)

- Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Screenplay by Christopher Markus & Stephen McFeely (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures)

- Edge of Tomorrow, Screenplay by Christopher McQuarrie and Jez Butterworth and John-Henry Butterworth (Warner Bros. Pictures)

- Guardians of the Galaxy, Written by James Gunn and Nicole Perlman (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures)

- Interstellar, Written by Jonathan Nolan and Christopher Nolan (Paramount Pictures)

- The Lego Movie, Screenplay by Phil Lord & Christopher Miller (Warner Bros. Pictures)

Andre Norton Award for Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy

- Unmade, Sarah Rees Brennan (Random House)

- Salvage, Alexandra Duncan (Greenwillow)

- Love Is the Drug, Alaya Dawn Johnson (Levine)

- Glory O’Brien’s History of the Future, A.S. King (Little, Brown)

- Dirty Wings, Sarah McCarry (St. Martin’s Griffin)

- Greenglass House, Kate Milford (Clarion)

- The Strange and Beautiful Sorrows of Ava Lavender, Leslye Walton (Candlewick)

I have friends whose work is included here. Charles Gannon, Ann Leckie, and Jack McDevitt (novels) and Daryl Gregory and Lawrence Schoen (novella category). Congratulations to them and good luck.