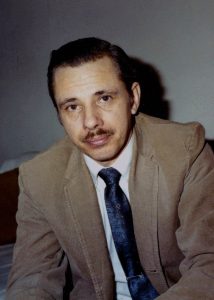

Because I really don’t want to write anything heavy or long, accept a couple of new photographs. I’m fine, I just need to recoup.

Thank you.

Because I really don’t want to write anything heavy or long, accept a couple of new photographs. I’m fine, I just need to recoup.

Thank you.

He did not care for his name, either his given one—Henry—or the nickname he ended up being known by, Hank. At his last job, he became known as Hank the Crank. It was an affectionate sobriquet. He managed a department full of engineers and took care of them. One of the first things he did when he took over was get them all raises which had been long overdue.

He flourished in that job. At the end of decades of struggling, moving from one place of employment to another, seeing opportunities die, usually in the mismanagement of others, he came to a place where all his unique and quirky skills and proclivities came together. For the years he managed that department, he was, as they say, in his glory. It was good to see him so enthused, all his faculties engaged. He would have worked at that till he died given the chance, but once again forces beyond his control took it away.

But he retired with his wife, my mother (though it was a few more years before she left the working world), and they bought a new house and settled into a suburban neighborhood (to my surprise, actually) to enjoy each other. I think they did. For a couple of decades they were able to be with each other in a way they might only have imagined possible.

Then the health problems began. Little by little, this man I had viewed as a kind of superman began to diminish. He had always been a private and often reticent man, so complaining was not part of his repertoire. It must be said that had he complained a bit more, things might have been easier for him. But he had difficulty admitting he needed help and for most of his life he had always been the one to be relied upon by those around him.

Compensation for his willingness to Be There had never been a consideration

My parents’ romance was the stuff of movies. They certainly didn’t see it that way, but when you hear the way it happened you can’t help but be charmed. He was in the army, stationed at Fort Leonard Wood. After basic training, his original unit was set to ship out to Spain, but he was pulled at the last minute because of his teeth. On his first leave, he and a buddy came up to St. Louis. They were at the Hilands, which used to sit on the ground that now supports Forest Park Community College. The Hilands was an amusement park, right on the edge of Forest Park. After a day of enjoying the rides and attractions, they were about to try to find a hotel. At the bus stop, they spotted two girls. They approached looking for directions and ended up riding the bus with them down town.

Dad must have been immediately smitten. Soon enough they were exchanging letters. Mom told me he very quickly wanted to meet her parents. At some point, she became smitten, too.

They decided not to marry until after his service was done. He was cognizant of the possibility of injury and had scruples about burdening her with an invalid, but the fact is he never saw combat. He ended up on Hokkaido across a stretch of water from Korea and never jumped off into the fray. He came home intact and they married on New Years Eve 1953.

I was born in October 1954.

From all I have gathered, dad did everything he could to make a fine and nurturing home. He had come from domestic circumstances that were far from ideal, from an alcoholic and abusive father and an apparently resentful if dutiful mother. He had been a late baby for her, giving birth to him when she was 40. While that is less uncommon today, in 1930 that was not only unusual but entailed more risk. There was a considerable age difference between Henry and his siblings and he ended up the last to leave home, which he had to do under fraught circumstances. It seemed that he was determined to do better for his own family.

From all I have gathered, dad did everything he could to make a fine and nurturing home. He had come from domestic circumstances that were far from ideal, from an alcoholic and abusive father and an apparently resentful if dutiful mother. He had been a late baby for her, giving birth to him when she was 40. While that is less uncommon today, in 1930 that was not only unusual but entailed more risk. There was a considerable age difference between Henry and his siblings and he ended up the last to leave home, which he had to do under fraught circumstances. It seemed that he was determined to do better for his own family.

And he did.

It has taken me a lifetime to appreciate what he did.

When you grow up in a bubble it never occurs to you to examine the surface of the bubble. As with most people probably, I underappreciated what my parents were like and what they did for me. In the last few years, I’ve been having longer and deeper conversations with my mom and I’ve been learning things about dad I might have suspected but never knew. I always knew, for instance, that he’d had a rough childhood, that his father was bitter and often cruel, but I never knew quite how deep the ambivalence ran with his mother and some of the details about his siblings…

All that to give context to the fact that he did a phenomenal job of breaking a nasty cycle. I was cherished and nurtured and provided with a wonderful example of a mature relationship because it has always been obvious that my parents were crazy about each other and also best friends. They shared a true partnership. In the context of the times, this is a remarkable thing. Dad insisted that mom have her own credit card and have her own car. He fostered her independence.

The biggest source of friction between my dad and me had to do with that. Independence. He wanted above all to be sure I was prepared for it. It seemed he often despaired of that since I seemed not to Get It. He was a Depression Baby, I was raised in a comfortable home and need was kept at bay to give me room to be what my dad had never had much chance of being—a kid. So our apprehension of the world conflicted. Even so, he did not back off from care and sustenance and respect. He suffered silently for the most part and hoped things would come out right.

He served in the army, came home, married my mom, and then landed a job at Remington Rand as an office machine repairman. At the time it was a well-paid job. During that time he and mom converted to Mormonism, which in hindsight was weird. Then came the first major break in what I eventually realized was my dad’s inability to compromise on certain principles. The church abused his fidelity and suggested going around The Rules so he could take on work they wanted him to do. When he called them on it, their response drove him to sever ties. I learned eventually that he was what I came to call a 110 percenter. He committed, he gave more than his all, but there was an implicit understanding that the thing he committed to must be just as committed as he was. He walked away from jobs, a church, a business he loved because it had become compromised and soured for him. If he felt his integrity was at stake, he walked away.

He taught himself machining and worked for many years as a journeyman machinist. This led to better money than he had been making and things got easier. During this period, he became a Freemason. One is never not a mason, so while his ardor cooled, that tie was never broken.

We did not quite Get each other. He tried. He tried harder than I knew. When I found something new, he was interested. The closest we came to sharing a passion was photography. He simply did not have time to get into it the way I did, but he always supplied me, and it led to a career. When I made my first few forays into writing fiction, he took an interest, but we both realized quickly that he would not be a useful critic, but he was clearly proud of me when I published my first stories and then novels. He would brag about me to strangers.

For all that he was a gregarious man, he was intensely private. As the world changed around him, many of our conversations took on a tone of bewilderment, sometimes anger, but he always tried to understand. Always. That willingness to try set him apart from so many people I have known. That he succeeded as often as he did amazed me. I can only hope I returned the courtesy.

He lost he eyesight and his hearing. Arthritis took his ability to get around and he began falling. Finally, one night, mom called me to come help. She could not get him up. We spent a few days until finally she called 911 and they took him to the hospital. From there, he went to a care facility. We were very lucky in the quality of the place. They cared, they gave a damn, and he became, as so often happened with him, popular with the staff, even though he could not communicate very well.

He was there two-and-a-half years and for most of that time he was stable. Last week he stopped eating. We saw him one day and he was clearly struggling, but there wasn’t anything specifically wrong with him. This past Friday he passed. The staff gave his body a surprising send-off.

I am a child of the whole self-analysis era. I learned the hard way, though, that leaving things unsaid is both unnecessary and harmful, so dad and I had had our “final” conversations. We had no unfinished business. That in itself does not secure one from pain. But it is not, for the moment, the raging pain of someone who failed at important exchanges. Dad and I were good with each other. No regrets.

But I am sad. Not that he’s no longer in an absurdly unpleasant situation—he had been vital and active most of his life, to see him unable to walk down a hall was difficult—but that he is gone from everything but memory. He mattered to people who came to know him. He was a Presence.

I love him. He was a great dad. And a good man.

CNN aired its town hall with Trump and received some criticism for it. But it had been scheduled for a while and since the Right likes to accuse the Left (which CNN is at best only an honorary member) of Cancel Culture, the question to air or not to air doubtless prompted them to err on the side of not canceling. Nevertheless, opinions about the man on the stage notwithstanding, I have no carp about that. The only downside to something like this is that it took up space where something else of presumably more value might have been aired. As that seems rarely a consideration in the board rooms of media companies (what is value? what is worthwhile? what is meaningful? ratings) I’m fine with them going ahead. I am fully capable of exercising my prerogative to not give him any oxygen or eyeballs (mine) and attend to something else.

What I do find useful is the polling afterward and as reported during the audience response. Applause, cheers, enthusiastic support from his supporters. After all the demonstrated toxicity inhering to the man and even after the just-finished libel case that did not go his way, he has followers who bathe in every insipid utterance that falls from his mouth. We have, the rest of us, been scratching our heads and asking why since 2015. What seems obvious to us appears to be grounds for adulation for them and we are profoundly puzzled.

When stripped of all the polemic and rube-goldberg extrapolation and analysis, this tells us something about populist politics that is very useful to recognize. Hard to accept, yes, but real nonetheless, and I think it time we deal with it directly. Going all the way back to the Founding, we have heard warnings about it. Many of the Founders did not trust democracy. We keep hearing that and consider it an aberration, but in truth they recognized something basic about the relation of government to the governed that we are now seeing in full cinematic glory.

What do people want from their government?

This questions is at the heart of this phenomenon and it’s time we faced it and recognized its consequences. We can point to examples throughout history in which the same issue has so distorted a nation’s social and political landscape as to cause dismay and horror at the result. What were they thinking?

To my mind, this question can be answered by three related but distinct apprehensions.

For most of us, here, we want government to reflect our values. By this we implicitly acknowledge that sometimes our choices in how those values manifest may be off the mark and we presumably put in place people who can parse the complexities and do what is proper according to the basic ideas inherent in those values.

For others, we want government to validate our values. That is, we want government to reassure us that we feel and believe that which is right and beneficial. We may not be entirely certain what our own values are. We might have a good sense of them, but what does that mean? Does everyone else feel the same way? In this we wish our representatives to reassure us that yes, we are part of a community that shares what we feel.

Then there are those who want government to validate their prejudices. What we dislike, disapprove, disdain takes the place of a positive set of values because all we can see or feel is that which makes us distrust or resent. Maybe we feel that if only all those things we think do not belong can be gotten rid of, things will be all right, and by that I mean things will go to our benefit. This leads, if unchecked, to a policy of discrimination, of segregation, of injustice, of hate. You can see this in political movements the sole purpose of which is to take things away from certain people.

This latter group is what we see in Trump’s base. He has from the beginning validated their resentments. Nothing he says or does matters other than as a target for the kind of response from those they scorn. He has told them, by word and deed, that they’re right to feel besieged and that who they feel they are is fine. In fact, more than fine, it is what being an American means.

They love him because he validates their resentments and prejudices and fears of the Other.

Trying to reason with them repeatedly fails because the rest of us always start with the wrong set of assumptions. In aggregate, they do not want to be more inclusive, but the opposite. When he made fun of the disabled journalist, most of us were horrified. His supporters reacted against our horror by doubling down on their presumed right to make fun of who they want, to laugh at things rather than grow any empathy, to find humor in tasteless reductionism, and to ultimately sort people into Us and Them camps based on nothing but an unwillingness to extend themselves to consider that intolerance is shameful and destructive. Much of this is aesthetic.

So I’m okay with seeing this aspect of our culture on display where we can come to terms with the irrationality and pettiness of it. I just wish more of us would get over our reluctance—a reluctance often born of those values most under threat—to call it what it is and then take steps to counter it. Effectively countering it, though, necessitates dealing with it as it is, not as what we wish it were. Many of us resist seeing others in such starkly unflattering light. We tell ourselves there must be deeper causes, more complex meanings, that it can’t be that base and simple. Well, the circumstances in which this thrives are deeper and more complex, certainly, but the people rushing to cheer on the evil clown are not. They have lived by stereotypes and clichés—such things have allowed them to feel good about themselves in their immediate surroundings—and they want their government to tell them they have been right about all that.

And then…there are those who know perfectly well what this is and are willing to take advantage of the chaos to gain power and/or profit. They aren’t at the town halls cheering. They are watching and checking their ledgers and waiting for the rest of us to do nothing.