Tomorrow, June 26th, is the 22nd anniversary of my arrival at the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Workshop, on the campus of Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan. The following piece was written for an anthology about Clarion several years ago, one which firstly did not take the essay and secondly seems not to have appeared at all. Be that as it may, I’ve decided to post it here. Enjoy.

And to all my fellow Clarionites, Happy Anniversary.

Baked Grass and Surgical Evisceration

The room could double for a steambath late into the night. When we arrived—seventeen of us from Maine to California, plus one from England—the weather was the last thing on our minds. Now, four weeks into it, ignoring the weather was a consuming pasttime. East Lansing was a torpid landscape of browning grass, heat mirages, and wilting humans. Earlier it had been 103; as the sun vanished it left behind an afterwash that, I swear, raised the heat index.

Owen Hall. Seventh Floor. So this is Clarion.

When I had applied for the workshop it was an act of measured desperation. I’ve always, in one way or another, wanted to be a writer, but not until 1981 or ’82 had I done anything about it. Even then it was more a hobby than—well, than the passion it has become. In the fall of ’87 I filled out the applications, placed my two stories with them into an envelope, and sent them on their way, like a bottle with a note for help cast out to sea. I had every expectation that this, like most of what I had written in the previous five or six years, would be rejected. I had solemnly told my companion-best friend-lover Donna that if Clarion did not want me I would give it up. The writing. Like a junky I was not at all certain that was possible. But rejection after rejection adds up and the demand of the Gods Who Edit And Write The Checks seemed unachievable. I had reached the end of my sanity. I had no idea why I was unable to write salable work. I had no idea what I was doing wrong. I had no idea why my offerings came back unwanted. If there was one thing I knew clearly about my expectations of Clarion it was that this question be answered. What was I doing wrong?

Being accepted to Clarion was not quite as great a relief as a cancer patient being told he is in remision—but I think I have an inkling what that must feel like.

Now, the heat sapping what energy was left after workshopping and writing, my thoughts drifted toward doubts of a different, though kindred, sort.

What the hell am I doing here?

Long distance to Donna (glumly): “I don’t know what I’m doing here. There are some incredibly talented people here. I feel like…I don’t know…I don’t measure up.”

Donna:Â “Do you want to come home?”

Me: “I don’t know. Yeah, maybe.”

Donna: “Okay. Then walk. And make sure you bring everything with you.”

I had brought a coffeebrewer, my own coffee, a MacIntosh computer, half a dozen reference books, a tape player and two dozen cassettes, vitamins, and clothes. Oh, yes, a small portable fan, which in this heat had become a cooling fan for the computer, lest it seize up on me and mightily crimp my progress.

The white screen of the MacIntosh seemed as daunting as the proverbial blank sheet of paper so many writers have mentioned. I was supposed to fill that screen. Hm.

Clarion was a six week escape. I had never had, and would probably not have for a long time afterward, so much time to simply write. I wanted to take advantage of it. I hyped myself into overdrive whenever the least thread of a story line presented itself to me. Get it out, get it on the disks, don’t let it get away whatever you do!

Fourth week. The story I had finally finished the previous night had come out easily enough, but then I printed it out. I listened to the insect buzzing of the printer and with each pass of the ribbon felt worse. Another piece of crap. Another failed experiment. It had a beginning, a middle, and an end. So much for improving.

I stepped out into the hallway while it printed. From around the corner at the far end—emerging from the “girl’s hall”, a result of MSU sexual prudery or something (which never made sense because there were regular MSU students of both sexes strewn up and down both corridors, which meant only the Clarion students were segregated…)—Daryl, Andy, and Brooks came advancing toward me, Andy aiming a video camera and Daryl reciting some narrative like a demented Inside Edition reporter.

Everyone ended up doing a spot for Daryl’s tape, a video documentary of bits of Clarion. When the excitement had died down and the camera was gone, I went to bed.

Swelter, swelter. Listen to heat melt the oxygen in the air.

In the morning I woke to the gurgling of my coffeemaker. I looked over the story again, grimaced (there is a word, are we in the sf genre aware? that almost never appears in any other form of fiction, and I have heard solid arguments from english professors why sf will never be significant because we insist on using “grimace”), and stared out at the highrise shimmering across from our building. It was already too damn hot.

I read the last story that had to be critiqued that day, made my notes, knocked back some more coffee, and dressed. I left my cubicle and headed for the back stairs.

Behind Owen Hall a narrow river, the Red Cedar, runs through the campus. A forest area sprawls against the river. There are trails and it is preternaturally quiet and beautiful. I had gotten into the habit of going this way to Van Hoosen every morning, camera in hand.

Van Hoosen is a conference hall connected to rows of fairly nice apartments surrounding a grassy courtyard. The writers-in-residence live in one of these spacious apartments. They are air conditioned. We had commented to Al Drake and David Jones, our director and assistant director, that many of these other apartments seemed empty. It would have been nice to have been allowed to occupy them rather than the monk’s holes on the seventh floor of Owen.

“Expensive,” David had said.

“They’re empty,” we replied.

Van Hoosen was air conditioned. Mercifully. I handed my manuscript to David for xeroxing and got another cup of coffee.

This was week four. First we’d had Tim Powers; then Lisa Goldstein; Chip Delany; now we had Stan Robinson. Stan brought with him memories of his Clarion experience, a quietly academic approach, a croquet set, and we were considering blaming him for the heat.

The workshop was conducted in the round. Each of us took a turn, rotating clockwise, starting at the given week’s instructor’s left and coming full circle back to him. After the writer, then Al Drake would add something. Each of us did what we could to avoid being First.

It’s difficult to describe what goes on at such a workshop. Stan had congratulated us for not indulging in shotgun/machinegun crits, as, he explained, had happened during his Clarion. We spoke to the story in hand, examined it technically, almost clinically, and tried to keep our visceral reactions objectifiable. Sometimes that wasn’t possible. Sometimes a story was either too good or too bad to be objective about and sometimes that aspect had to be addressed. But we tended to be—if this is applicable to students—professional about it. From some of the stories I’ve heard some workshops had been bloodier than a Brian dePalma flick.

The workshop went until lunchtime. Then we had time to write. Or wander the campus. Or go into town and blow it off.

I was written out. I felt dismal about my story. I mentioned it to Kelley, but I couldn’t explain without telling her the story, and we had all gotten into the habit of not discussing the specifics of our stories before they were written. I felt by and large out-of-place here.

I grabbed my cameras and walked down Bogue St. into town.

Bogue dead-ended at East Grand River Avenue, which borders the campus, separating it from East Lansing proper. It’s a broad street with islands running down the center, and containing shops, restuarants, message boards with layers of posters and personal notes tacked to them. One of these boards had caught fire recently; no one had cleaned off the charred remnants and now more messages were being tacked over the blackened tatters.

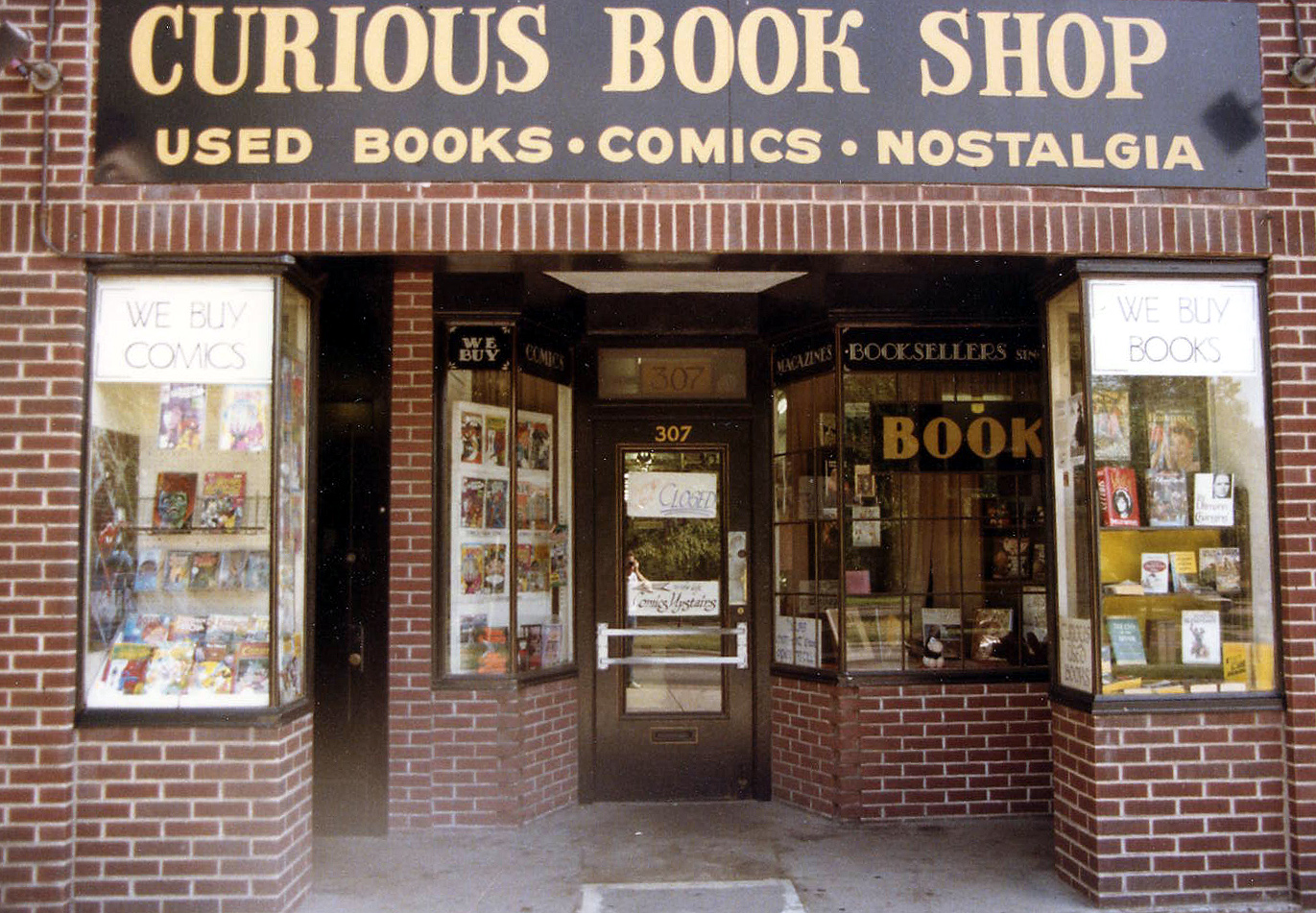

I hesitated before Curious Books. This had become the bookstore of choice for us, not least because the owner, Ray Walsh, had arranged for each of our instructors to do a signing every Wednesday. It was a wonderful bookstore, crammed with used and new, the air permeated with the heady odor of printed matter. I’d already spent a small fortune here. I walked by.

I went straight to the Olde World Soup Kitchen. As far as I had been able to tell I was the only one who had discovered this place. I adore a good bowl of chicken soup (they make excellent sandwiches, too) and I wasn’t unhappy about being alone. I could sit and think.

Some of the things I thought about were facets of Clarion that nobody ever talks about—at least, they didn’t tell me.

One: you learn just how much you can accomplish on five hours or less a night sleep.

Two: there are worse things than not being able to write at all—being able only to write garbage.

Three: you discover just how much alcohol you can take in and still be coherent. Sort of.

Four: the workshop structure of Clarion lends true insight in just what an editor must go through daily dealing with the slush pile.

I had my soup and a sandwich and I thought about these and other things. No conclusions, just mental exercise. At this point I wished I could have turned my brain off for awhile. When I had no more excuses I stepped once again into the blastfurnace and made my roundabout way back to Owen Hall. As I entered the lobby George was passing through.

“David’s looking for you,” he said. “Something about missing a page of your story.”

“Shit. Where is he?”

George had a number jotted down and I called on one of the lobby phones. David explained that I was shy the last page of my story, could I get him another and run it over to him?

What else was I supposed to say? No, David, let everyone read the damn thing and guess the ending. I ran up the stairs—the elevators took too damn long—sprinted to my room and booted up the story. I printed out the last page, closed everything down, and bolted for the stairs again. The copy room for our use was two buildings away. I ran.

When I entered the building I encountered a large group of Asian exchange students, all talking animatedly in their own tongue. I strode through them, silent, out-of-breath, and sweating profusely, a lone sheet of paper in my hand, and somehow did not seem to attract their attention.

David was in the basement. His eyes widened slightly when I entered the copy room.

“Here,” I said, handing over the page.

“Thanks. I’m sorry about this.”

“No problem. My fault. But I don’t understand how one page could’ve gotten lost.” I glanced at the pile of copies he’d been running. We had a lot to read tonight. At least I didn’t have to go through my own story again.

“Well, yours was the last one in the stack and I’d gotten all the rest copied, then I couldn’t find the last page.” He scratched his head. “I’m glad George found you.”

I opened the copier lid. A sheet of paper lay there. I picked it up. We both stared at it. My original last page. David winced.

“Sorry.”

I didn’t mind too much. This building had fully functional air conditioning.

When he finished, I walked with him back to Owen, talking about various things that didn’t require a lot of thought. David slid the copied stories under the door of each room containing a Clarionite. As I watched each copy of my effort disappear under each door I felt worse by degrees.

We parted at my room and I locked the door behind me. The small, rather noisy refrigerator I’d gotten from management contained a couple of six-packs of wine coolers. I stripped, showered, and sat staring out the window, downing one after another. In the middle of the third one I started reading the small pile of stories.

I’m a slow reader. I was worried about that when I came and found out what the schedule was. I had to read all these tonight, critique them, and be ready to be constructive in the morning. As long as the stories were short I had no trouble, but once in awhile someone—like Daryl—would dump a novelette or novella on us, hence a night that basically allowed me about three and a half hours’ sleep. Tonight there were four stories, including mine. Well, I didn’t have to read mine. One of the others was about nine thousand words. I read that first.

It was dark by the time I finished the other two.

I was on my fifth cooler.

Instead of trying to sleep in the sauna of my room, I decided to go down to Stan’s room to soak up some atmosphere—cooled atmosphere.

(I’m also not a party sort. I tend to be horribly shy in groups larger than two, so I hadn’t attended very many late night bashes with instructors. To be fair, there hadn’t been many till Stan’s week.)

When I arrived at his room, my head nicely encased in cotton from the coolers, things were quiet. Stan was holding forth about his Clarion. Andy was there. Sharon and Glenda, too. I had no idea what time it was. I helped myself to a glass of white wine and sat and listened.

“—no, we weren’t even here,” he was saying. “We over in ____ Hall. The workshop room was in the same building.”

The air was nice. I sort of nodded off.

“Wanna go for a walk?”

I looked up. Andy was standing before me. “Hmm?”

“We’re going for a walk with Stan,” he said.

“Where?”

“Over by his old hall.”

I glanced at my watch. It was nearly midnight. I was tempted to stay in the room and enjoy the air, but what the hell? I had missed a lot of this sort of thing so far (I thought) so I shrugged and stood.

It had actually cooled down somewhat. The night air was maybe ninety degrees? The grass crackled sadly underfoot, like we were walking on small snack crackers.

The stars were brilliant, though.

Stan spoke in semi-reverent tones about water fights, group readings, the horrible cafeteria food, tristes, trials, and travesties. I thought, my what a placcid, boring group we are compared to his. (Later I asked Damon about that and he opined that the 88 Clarion class was an older median age than the others, older enough that we didn’t—well, behave younger.)

We arrived at a gothic manse of a building that hulked in the night like a troll’s mound.

“This is it,” Stan announced and bounded up the front steps. He grabbed hold of the door handle and pulled. The doors rattled. “It’s locked…” He tried the other doors. “What time is it?”

“Twelve ten,” I said. I stood next to Andy, hands in my pockets like a tourist, watching Stan go from door to door, peer through his framed hands into the dimly-lit interior, grow visibly disappointed.

“I guess they lock up at midnight,” he said. “Well, my room was over here.” He crossed the law (crackle, crackle, crackle) to a row of windows that looked into the basement. He started searching. “Damn. They aren’t dorm rooms anymore. They look like store rooms.”

I walked up beside him and looked in. Boxes, old desks, unmarked rolls of something (maybe maps) filled the rooms. Stan went to the next, then the next.

“I don’t remember which it is,” he said.

“Let’s try the back door,” Sharon suggested.

I nodded and followed Glenda and her to the rear parking lot. The doors were all locked. Stan and Andy came around then, Stan talking once more about his days at Clarion. I told him none of the doors were open and he gave the building a sort of wistful look.

“Oh, hell,” I said, pulling my pocket knife out, “there’s always a way in.”

Stan looked at the knife. “What are you going to do?”

I shrugged. “Find a way in. What are they going to do, arrest us?”

Stan frowned. “I don’t think that’s a good idea.”

Andy was grinning.

“For nostalgia’s sake?” I suggested.

Stan shook his head. “No. Let’s get back. It’s not important.”

I raised my eyebrows, trying to look very Spockian, then shrugged and closed the knife.

We wandered back to Van Hoosen. Daryl was walking his computer down from Owen.

“What are you doing?” Andy asked.

Daryl gave us a frantic look. “I can’t take it anymore! I’m melting! I can’t think! I won’t stand for it, I tell you, I just won’t!” Then he grinned. “I’m setting up in Van Hoosen.”

I faded away from them then and wandered back up to my monk’s hole. The coolers, the wine, the walk—hell, I passed out.

In the morning I woke up and sat on the edge of my bed staring at the coffeemaker that I had forgotten to set. No coffee. Shit.

I splashed water on my face, then made coffee.

A note had been slid under my door in the night. Sleepily, I scooped it up and returned to the edge of the bed. The coffeemaker gurgled energetically. After a couple of minutes I turned on the stereo behind me. Genesis came out.

I opened the note.

“Mark: just wanted you to know, loved this story. Your writing gets clearer and clearer. Keep up the good work. Kelley. Ditto, Mark. Nicola. Me, too. Glenda. Chin up. Peg.”

I sat there with a goofy grin—I could feel it, I know when I have a goofy grin—staring at that note. In one note I went from maudlin to mushy.

Later, in the workshop, they eviscerated that story. Of course. Being a friend means being honest.

That was the other thing nobody told me about Clarion.

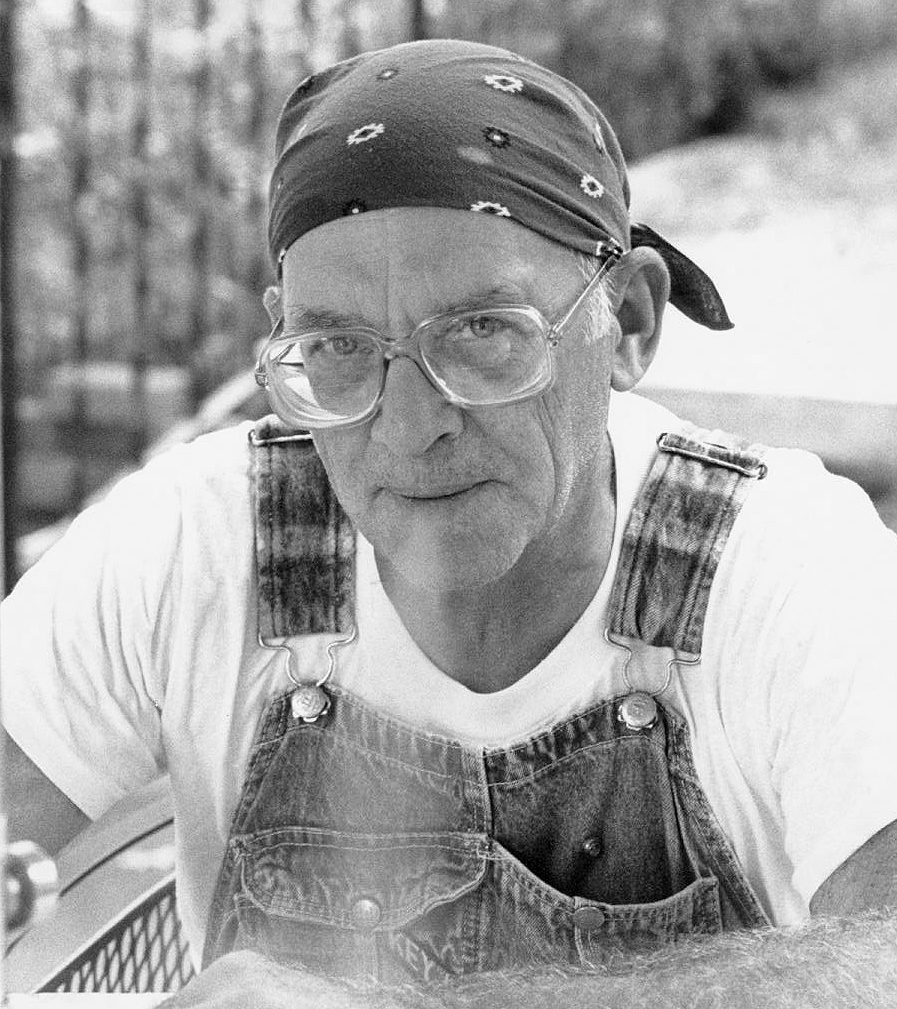

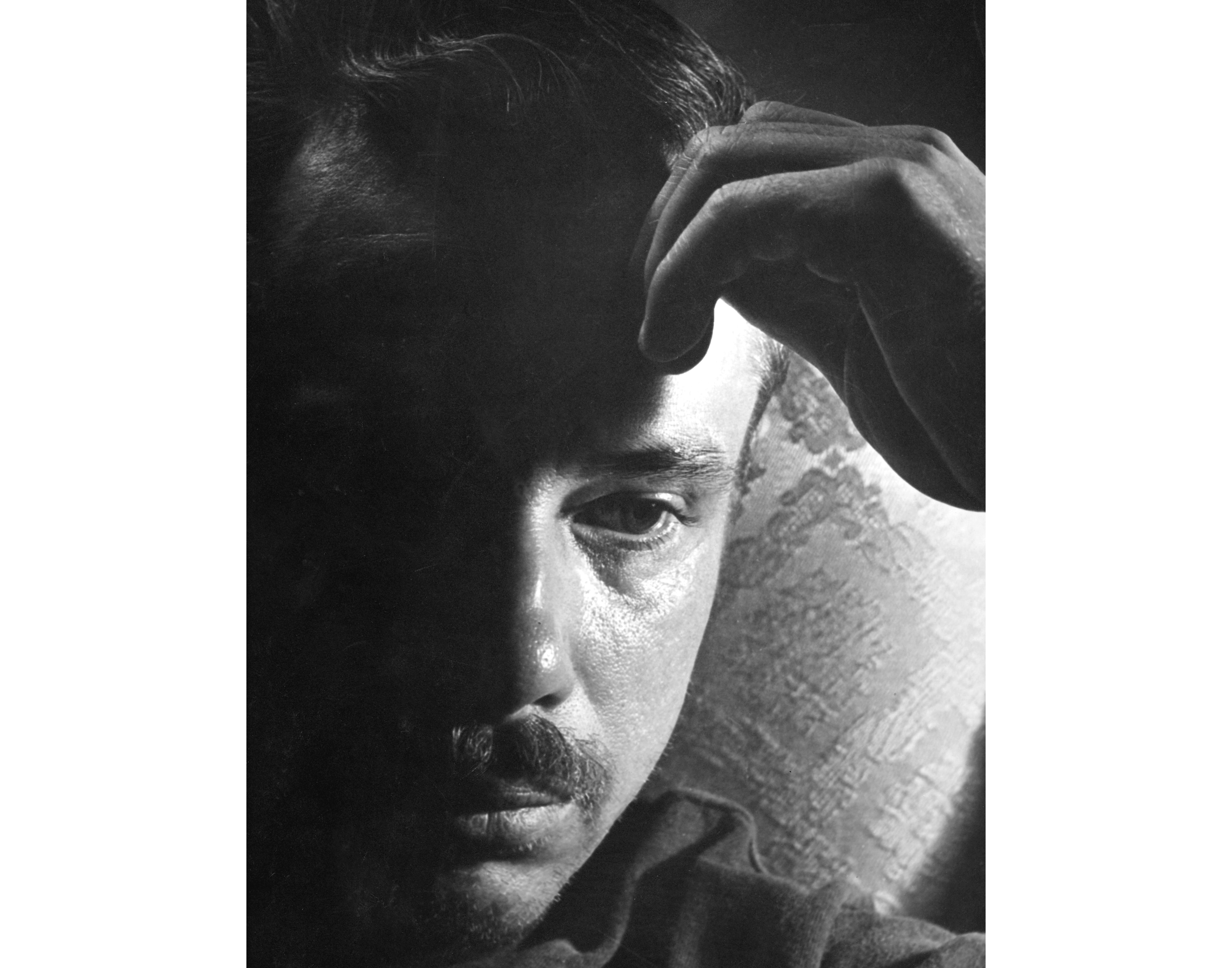

New Fantasy Thugs, Clarion class of 1988:Â l to r (roughly)Â Lou Grinzo, Jay Brazier, Daryl Gregory, Kimberly Rufer-Bach,Kelly McClymer, Mark Tiedemann, Peg Kerr Ihinger, Brookes Caruthers, Sharon Wahl, Nicola Griffith, Kelley Eskridge, George Rufener, Glenda Loeffler, Sue Ellen Sloca, Mark Kehl, Andy Tisbert