My dad. I have a lot of mixed feelings about him, as every child does even if they don’t admit it. Most of mine are positive.

To be clear, he is still alive. He’ll be 80 next month.

In his own way, he encouraged me in just about everything I ever did. The problem usually was that I didn’t appreciate his encouragement. Partly this stemmed from a profound misunderstanding between us of the reason for his encouragement—or perhaps I should say the purpose behind it. See, Dad was a Depression Baby. Even in today’s economically stressed climate, most people born during or after World War II really don’t grasp all that meant. For one thing it didn’t mean the same thing for everyone. But for everyone of that generation, it meant something that drove them to make sure their children and grandchildren never had to live through such a time, or such conditions.

The irony of this—which I think was largely successful—is that the children of these people can’t grok the essential nature of their fears. Oh, you can think your way to it—after decades of wrestling with some of this I believe I can describe it and write about—but at the time of life when they are trying their damnedest to both impart their values and protect loved ones from the severities of the Depression, there is a profound mismatch of perception and apprehension. My parents both wanted me to be safe from what they went through—but they also wanted me to share the value they placed on money and caution and common sense and success. To succeed in one meant the failure in the other. I did not for years understand why my dad got so angry with me over how I went about choosing what to do with my time.

For what we had, my parents lavished me with largesse. I took an interest in art, materials appeared. I took an interest in music, a 1964 Thomas organ arrived in the house, state of the art with a Leslie speaker built in. I took an interest in photography, a lab arrived, then cameras, then more cameras, then supplies.

And there was Dad, peering over my shoulder, encouraging and sometimes driving me to master these things. It often led to horrible days of screaming and crying and nastiness. He could not tolerate mediocre work or ambivalence or sloppiness or…

Or the fickle attention span of a child.

What I did not understand until about a decade ago was this: all these things showed up, underwritten, sponsored, encouraged because he was trying to make sure I had a skill by which to earn my way in life. Whatever I wanted to do, he wanted me to do it at a level where I could make money at it. All of it was aimed at a career.

I was a kid. I wanted to play. We ended up dealing with each other at crossed purposes.

Had I known this then, I suspect I would have kept my interests to myself. I did finally do exactly that when I took up writing. That was the one thing I did not share with Dad.

But all the haranguing and yelling and insistence on quality that had preceded it ended up going into the work on the page.

I can say now that all he did I know he did out of love. He was trying in the best way he knew how to protect me. To make sure I’d be all right. He just neglected to tell me that’s what he was trying to do. I accepted all the things he and my mother provided as any child might, as expressions of indulgence. As toys. And I played.

Unfortunately, none of what he tried to help me do came to fruition in the manner he expected. He might have been happier had I become a studio musician, but learning to play in the traditional manner (lessons, constant practice of boring music, etc) left me cold and frustrated. I didn’t really start playing well until I got involved in a rock’n’roll band and of course that was music he couldn’t stand. (Even so, when he realized what was going on, he and mom actually went looking at portable keyboards and started learning what I would need if it turned into something. I nipped that in the bud by being secretive about it. No way did I want another two or three thousand dollar millstone around my neck. But they would have done it.)

The photography turned out to be different. He pretty much left me alone to pursue it the way I wanted to. And in my usual approach, I jumped head first into the most difficult parts, ignoring the tedious basics. Sure I wasted a lot of film, a lot of paper and chemistry, but in two and half years I was doing fairly high-quality work.

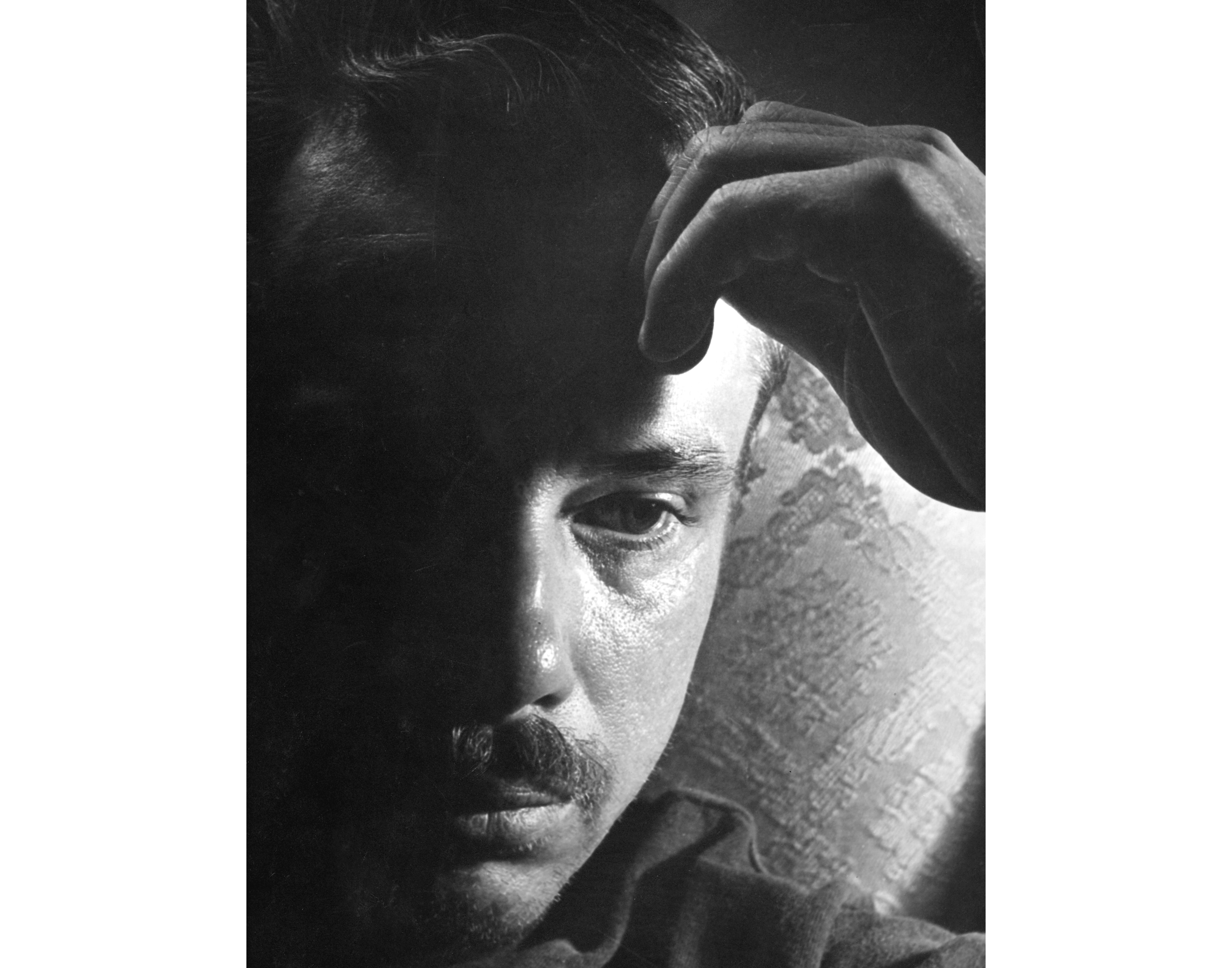

As an example, here’s a portrait I did of Dad that actually got some outside attention while I was still in high school.

This piece actually got entered into a state art contest. It made it all the way up to second place at that level and one result was to change the mind of the head of the art department about the value of photography.

At the time this image was made, Dad posed for a lot of pictures. He was still working as a machinist. Hard, intense labor at the time. These were the days before numerical control machines. He had to do the calculations by hand, load the steel stock by hand, operate the machines by hand. He was immensely strong at the time. He’d come home covered in sweat and grime, shower, sit, eat dinner. And then ask what I’d been up to and did I need help with anything.

He has always been there ready to help. So what if he got the method wrong? It wasn’t all wrong and the results were nothing to complain about (at least, I hope not).

After getting out of the shop—because he was the only one to volunteer to take the training when the company he worked for bought their first numerical control lathe—he worked just as hard to ascend a management ladder and ended up head of an engineering department with nearly a hundred engineers under him. He built an entire factory from the ground up for a single project and came in under budget and ahead of schedule. He taught himself four computer languages and learned the complex ins-and-outs of procurement for an international corporation.

He was retired—asked to do so, offered a big bribe to leave—because, despite all this, he only had a high school diploma.

As I said, he’ll be 80 soon. Physically, he’s much diminished. But the mind is still as sharp as ever and he still challenges me. And once the stories and novels started appearing, he was not at all shy about bragging on my behalf. (“I don’t know much about this literary stuff,” he told me once, “but your mother does and she’s says you’re a damn good writer.” Which meant he thought so, too.)

I found this photograph recently, scanned it, cleaned it up a bit. I thought I’d share a bit about my dad. He was and is Something Else. I love him.